Domaine de la Romanée-Conti: He bought a 127-year-old bottle of wine. Then, he opened it

Burgundy, France

—

In the private dining room of a Michelin-listed restaurant in east-central France, a small group of the world’s foremost wine authorities gathered reverently around a rather scruffy bottle, glasses at the ready.

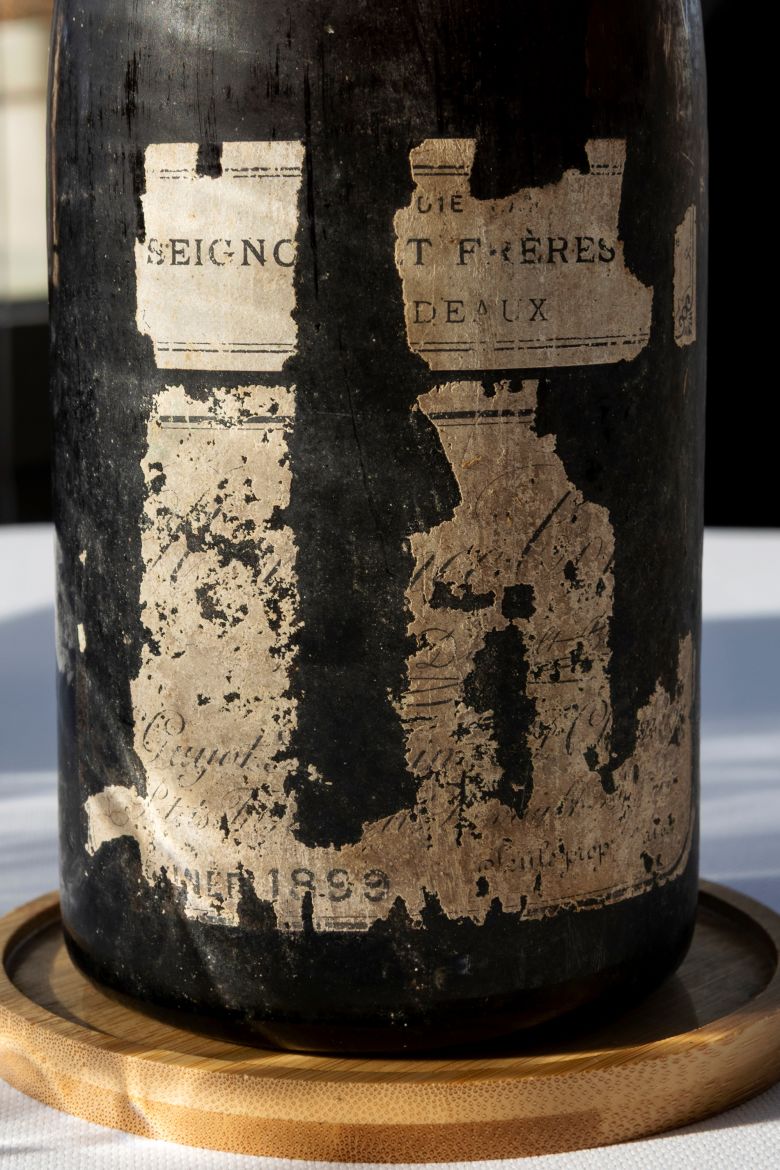

The object of their desire — encased in a heavily weathered label and lead capsule — was an 1899 Romanée-Conti wine, from one of Burgundy’s most revered vineyards, the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (DRC).

Once the preserve of European aristocracy, the Romanée-Conti is now sought out by multi-millionaires at auction. For an idea of its almost mythical status among wine connoisseurs, a 1945 Romanée-Conti became the most expensive single bottle of wine sold at auction when it fetched $558,000 at Sotheby’s in 2018.

Now, experts at the Auprés du Clocher restaurant described the antique bottle before them as a “unicorn.” Its 127-year lineage was verified by the pristine ‘1899’ cork marking, incredibly still visible through the glass — bearing the identical, historical font of the Domaine itself.

It’s the kind of legendary bottle that is usually traded — not tasted. Unless the owner happens to be Singaporean businessman and wine investor Soo Hoo Khoon Peng, who on a crisp winter’s day in January opted to uncork and share the prized bottle, 12 months after he purchased it for his 50th birthday.

“Too many great bottles are never opened,” Soo Hoo told CNN. “This isn’t about status, it’s about learning and human connection.”

Based on provenance alone, Régis Cimmati, fine wines director at Maison Pion, a key distributor of DRC, estimated the 1899 bottle to be worth €100,000 ($118,000).

In comparison, other DRC vintages from the last five years trade for between roughly €17,000 to €23,000 ($20,000 to $27,100). All the more remarkable then, that the 1899 lay forgotten for years in a cellar, before eventually ending up on Soo Hoo’s table.

The 1899 was originally purchased directly from DRC by the French noble family de Brou de Laurière, proprietors of Bordeaux dealer Seignouret, explained Cimmati. Its strip label, bearing the partially faded “SEIGN***ET,” was the first clue to its prestigious origin. “Famous producers used to add their distributor’s name,” he said.

For decades, the bottle lay undisturbed in the family cellar until 2011, following the death of descendant Patrick de Brou de Laurière. “The story is amazing because the label was damaged, and auction experts failed to recognize it,” Cimmati adds. “Hidden in a mixed case titled ‘19th-century red wines,’ it was sold for a few dozen euros at a local auction.”

Rescued by an astute buyer, it reached Soo Hoo early last year through Maison Pion.

“This bottle was not sold publicly,” said Cimmati. “It was offered to a handful of knowledgeable drinkers,” he said, including Soo Hoo, who insisted on opening it with Aubert de Villaine, the 86-year-old co-owner of DRC.

Soo Hoo has become a respected authority in the international wine scene. Along with co-owning vineyards in Burgundy, he also co-owns Australia’s Bass Phillip, widely dubbed the “DRC of the southern hemisphere,” and distributes legendary champagne Salon and cult Californian wine Screaming Eagle. His various business ventures also helped pave the way for the Michelin Guide’s 2016 Southeast Asian debut in Singapore. If anyone was going to lay their hands on a rare Romanée-Conti, Soo Hoo had the connections to make it happen.

A biological relic, the 1899 captures a vanished world. It was produced from ungrafted, own-rooted Pinot Noir vines — a practice later devastated by the arrival of the North American phylloxera insect in the late 19th century. While neighboring vineyards resorted to grafting their vines onto pest-resistant American roots, DRC used various intensive strategies to keep its original European vines intact, at least until the 1940s.

The bottle’s survival through two World Wars, the Great Depression and a century buried in a cellar is exceptional. “Only wines of the highest quality and aging potential can last this long,” explained Cimmati. “It requires impeccable, undisturbed cellaring.”

Critical markers confirmed its condition: the wine retained a “promising, bright light red” color, a key sign of life, said Cimmati. “Ullage (the air gap) drops about 0.5 to 1 centimeter per decade. At 6 centimeters after 127 years, the conditions are very good,” he noted.

Moreover, the bottle had only ever moved between Burgundy and Bordeaux, a driving distance of roughly 300 miles.

And as for the taste?

“Opening an 1899 Romanée-Conti is a landmark event for the wine world,” said Cimmati, one of the assembled guests for the highly-anticipated moment of truth. “These pre-war, ungrafted bottles are the pinnacle of the craft —they aren’t even supposed to exist anymore.”

Even the winter sun seemed to recognize the gravity of the moment, breaking through the clouds to illuminate the private dining room for the entirety of that historic afternoon. Its glow fell upon the select gathering, personally assembled by Soo Hoo — among them, founder of the Vivino wine app, Heini Zachariassen, certified Master of Wine and commentator Ned Goodwin and editor-in-chief of The Wine Advocate, William Kelley.

Seated beside Soo Hoo was DRC co-owner Villaine, a living link to the DRC’s 1869 owner, Jacques-Marie Duvault-Blochet. Incredibly, the 1899 predates even the oldest bottle in the DRC’s private reserve — a 1911 Richebourg.

So, what does a 127-year-old wine taste like? Glowing with a luminous amber hue edged in orange, the wine was warm with evolved notes of dried flowers, tea and preserved plum, yet animated by a delicate freshness.

“The very fact that the wine is still alive is a relief,” said Soo Hoo, his satisfaction evident.

“At 127 years, the primary fruit is gone,” observed Kelley, who drew the cork. “What remains is the wine’s heady vinosity, which was almost spiritous.”

“The purity and elegance are beyond comprehension,” added Olivier Pion of Maison Pion. “It is a miracle.”

In a time where fabled bottles are traded and shelved as trophies, Soo Hoo’s decision to open this one is radical. Cimmati called it the ultimate act of generosity: “Purchasing a relic of this magnitude simply to share it with peers proves his passion. He truly belongs among the top 100 figures in the global industry.”

“I don’t believe in speculation,” Soo Hoo said. “Opening such a bottle is not an act of extravagance, but of respect for the vineyard, the people behind it, and the moment shared. Ownership is temporary; experience is lasting.”

First Appeared on

Source link