Eating This Popular Korean Side Dish Daily Could Boost Your Immune System

A new South Korean study shows that kimchi, when consumed daily in powdered form, increases the immune system’s ability to identify and respond to threats, while avoiding the risk of overstimulation.

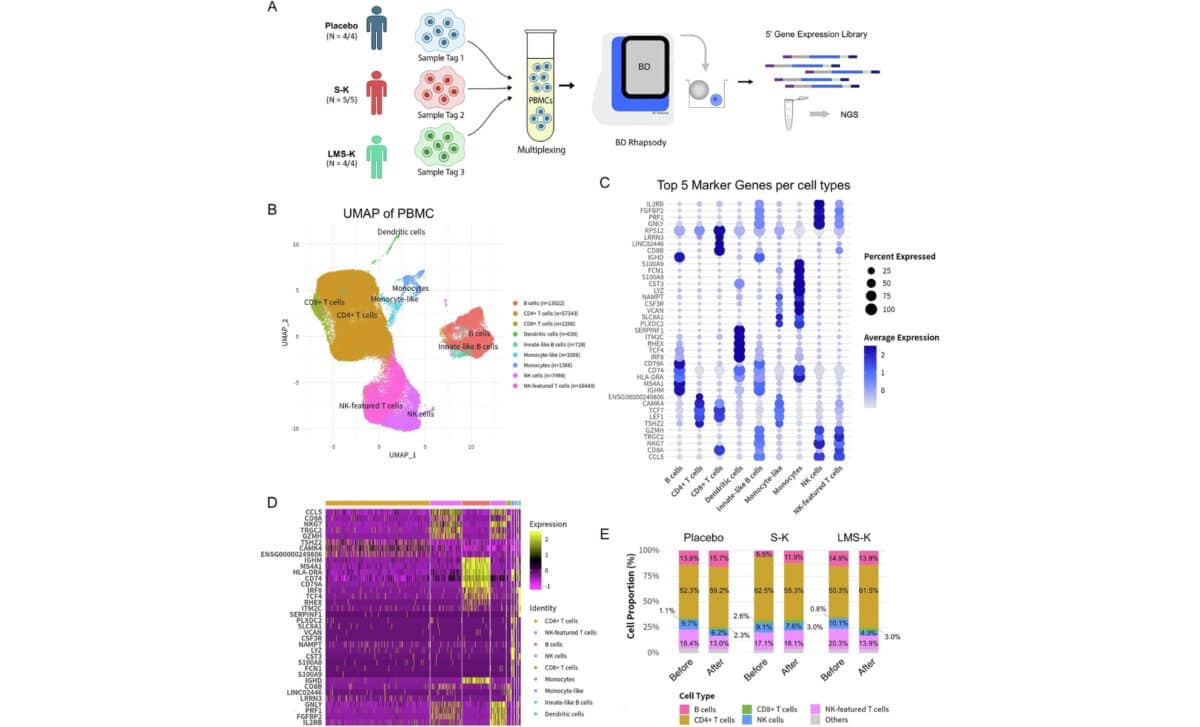

Led by Dr. Wooje Lee at the World Institute of Kimchi (WiKim), the 12-week trial involved adult participants who consumed kimchi powder made through different fermentation methods. Using advanced gene sequencing tools, researchers tracked how immune cells reacted before and after the intervention. The results pointed to a clear biological shift: better antigen recognition and inflammation control, two core pillars of a resilient immune system.

The research arrives at a time when interest in functional foods and microbiome health is rising. While previous studies have suggested general benefits of fermented foods, this investigation went further by examining individual immune cell activity using single-cell RNA sequencing. The work highlights not just a boost in defense, but a recalibration of the immune response, a balance often missing in immune supplements.

Targeted Changes in Immune Cell Behavior

Blood samples taken from the study’s 13 overweight participants revealed key changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which include T cells and monocytes. After kimchi powder supplementation, researchers observed a notable increase in antigen-presenting cells, those that capture protein fragments from pathogens and present them to other immune cells for recognition.

These cells showed greater activity in MHC class II proteins, molecules critical to mounting a specific immune response. According to Earth.com, immune cells treated with kimchi extracts were able to absorb and process more protein targets. This reflects a heightened readiness to detect viruses and bacteria.

At the same time, gene patterns indicated that CD4+ helper T cells were moving toward a more controlled, regulated activation. This restrained yet responsive behavior suggests a reduction in unnecessary inflammation, a key factor in preventing tissue damage during immune responses. “Our research has proven for the first time in the world that kimchi has two different simultaneous effects: activating defense cells and suppressing excessive response,” Dr. Lee stated.

Starter Culture Made a Difference

The method of fermentation played a distinct role in the immune effects observed. Participants were divided based on whether they consumed kimchi powder made through traditional fermentation or with a starter culture containing the strain Leuconostoc mesenteroides.

According to the same source, the starter culture version triggered stronger immune signaling, with more pronounced gene activity. Controlled fermentation using specific bacterial strains can shape the biochemical composition of kimchi, possibly enhancing certain health-related compounds. Still, both types of kimchi powder pushed immune cells in the same general direction, suggesting a shared underlying benefit.

The findings point to the influence of manufacturing decisions in determining the final immune impact of a fermented food product. Even dried and processed, the kimchi powder retained immune-active properties, reinforcing its potential as a functional supplement.

Precise Activation, Not Systemic Overstimulation

Researchers emphasized that not all immune cells were affected by the kimchi powder—an important observation in the context of immune regulation. B cells (which produce antibodies) and cytotoxic T cells (which kill infected targets) remained mostly unchanged, indicating that the supplement did not globally ramp up immune activity.

Instead, the effects appeared targeted. Helper T cells matured more rapidly, and a specific subgroup of proliferating T cells increased slightly, hinting at cellular renewal rather than exhaustion. Lab tests showed that kimchi extracts influenced interferon-gamma production, which in turn activated MHC class II gene expression. When a blocking drug (ruxolitinib) was introduced, the activation was reduced but not entirely stopped, indicating multiple immune pathways were at work.

While these findings are promising, the study did not measure actual illness rates or symptom reduction. Still, they represent an important step in understanding how fermented foods can interact with immune function. “We plan to expand international research on kimchi and lactic acid bacteria in relation to immune and metabolic health in the future,” Dr. Lee said.

First Appeared on

Source link