Fed on Reams of Cell Data, AI Maps New Neighborhoods in the Brain

The algorithm was also able to identify new neighborhoods, regions that previous neuroscience methods, including the Allen Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework, had missed. Take the striatum, a striped, vaguely C-shaped structure near the middle of the brain. In maps of the mouse brain, where the striatum is called the caudoputamen, “you just see one huge structure,” said Hourig Hintiryan, a neuroanatomist at the University of California, Los Angeles who wasn’t involved in the new project. It’s known to participate in movement, reward, and overall brain management. How could one piece of brain perform such disparate tasks?

CellTransformer’s explanation is that it’s not one uniform brain region after all. The map confirmed that the caudoputamen is, in fact, subdivided into smaller areas, although researchers have not yet matched each region to a function. Moreover, the new subdivisions corresponded nicely to a map that Hintiryan and colleagues published in 2016 based on an entirely different technique, which traced connections between the caudoputamen and other regions.

Identifying such subregions across the brain, Hintiryan said, could resolve debates between neuroscientists who assign vastly different functions to the same large brain region. It seems likely that “they’re both correct, they’re just looking at different areas,” she said.

Abbasi-Asl and Tasic were thrilled with CellTransformer’s ability to accurately match known brain cartography, and even more excited that the algorithm mapped novel subdivisions. For example, the brainstem’s midbrain reticular nucleus, which is involved in initiating movement, is a fairly underexplored region, Abbasi-Asl said. CellTransformer picked out four new neighborhoods there. Each of those neighborhoods featured particularly prevalent cell types and specifically activated genes. They also had several cell types that earlier analyses had placed in an entirely different part of the brain.

A Map in Hand

The Nature Communications paper serves mainly to introduce the CellTransformer method and show that it can find novel regions; the thousand-plus new neighborhoods still require validation. As with any exploration of new territory, drawing the map is just the beginning. What’s most exciting is what scientists may be able to do with it. “The more granular our understanding of structure, the more specific we can get with our interrogations and interventions,” Hintiryan said.

Emerging questions center on the functions of all these neural neighborhoods. To pinpoint what each bit does, scientists could eliminate or activate these newly identified regions in lab animals and then check for behavioral changes.

The real prize will be to apply CellTransformer to human brains. Doege suspects that some neighborhoods will match well between mice and people, while others will diverge. Unfortunately, the quantity of data the algorithm needs to make accurate predictions isn’t available from human brains — at least, not yet. While the mouse brain contains about 100 million cells, the human brain has around 170 billion, and that menagerie is still undergoing genetic analysis. When sufficient amounts of that data become available, Abbasi-Asl and Tasic think CellTransformer will be up to the challenge.

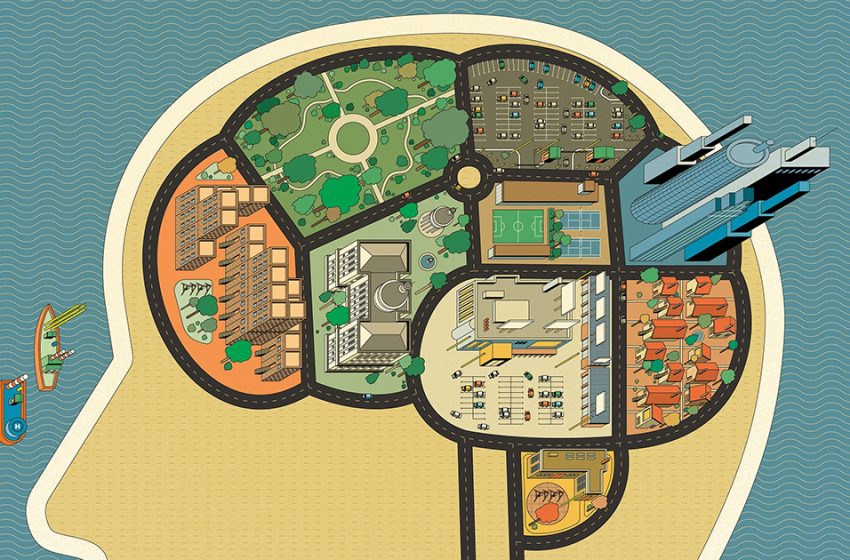

They are also interested in incorporating other technologies, such as the connection tracing used by Hintiryan, into CellTransformer. This would be like adding streets and highways to the city neighborhoods. And beyond the brain, the same algorithm could offer detailed cell maps of other organs, allowing scientists to compare, for example, healthy versus diabetic kidneys.

Human scientists simply can’t sort out these details on their own. “I see AI as kind of a helper for the human,” Kim said. “Discovery will be accelerated in a dramatic way.”

First Appeared on

Source link