Geologists Uncover Earth’s Largest Iron Ore Deposit Ever Recorded, Worth $5.7 Trillion

In a region long known for its mineral wealth, a recent geological study is prompting researchers to revisit some of the most fundamental assumptions about Earth’s deep history. Beneath the red terrain of northwestern Australia, new evidence has surfaced that challenges prevailing models of ancient ore formation.

The findings concern a specific type of mineral deposit that has shaped economies, industrialisation, and the structure of global trade for over a century. Its origins, until now, were thought to be relatively well understood, framed by textbook theories linking geology to early atmospheric shifts.

However, new dating techniques applied at key sites in the Hamersley Basin have produced results that deviate sharply from earlier estimates. The implications extend beyond resource geology, touching on how tectonic processes may influence mineral systems at the scale of continents.

Direct Dating of the Hamersley Deposit

A study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) has established that the vast iron ore bodies in Western Australia’s Pilbara Craton formed between 1.4 and 1.1 billion years ago. This age contrasts sharply with earlier models that placed the mineralisation event between 2.2 and 2.0 billion years ago, during what is known as the Great Oxidation Event.

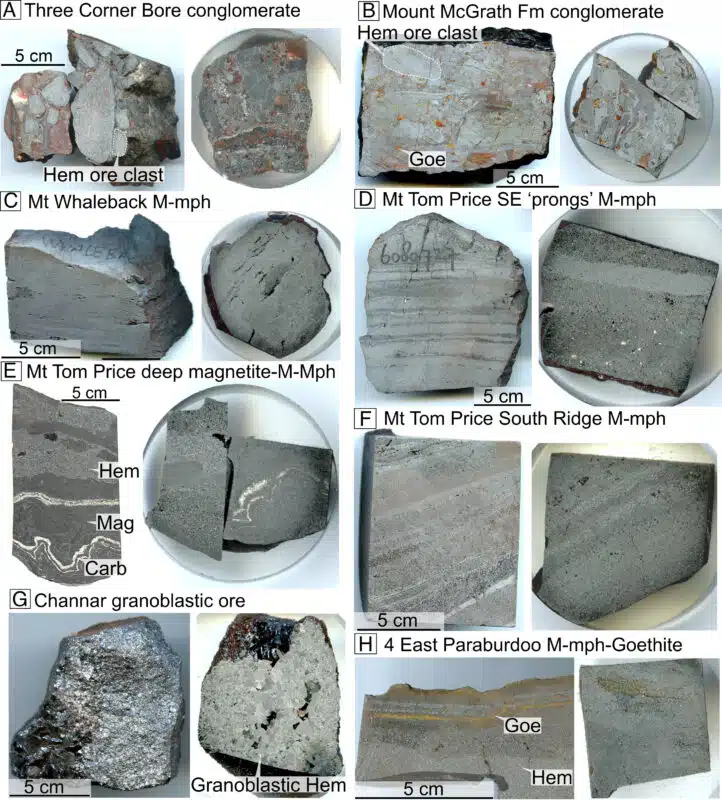

Using in situ U–Pb isotopic dating on hematite samples, researchers were able to determine the crystallisation age of the iron ore directly—marking a significant methodological departure from previous approaches that relied on dating associated minerals or stratigraphic context.

“No existing phosphate mineral dates overlap with obtained hematite dates and therefore cannot be related to hematite crystallisation and ore formation,” the paper notes.

The new age range has been confirmed across multiple ore bodies in the region. Further public coverage of the discovery, including reporting by Earth.com, highlights how this evidence challenges decades of conventional geological understanding.

The findings suggest the ore formed long after the commonly cited oxygenation events and instead aligns with tectonic activity linked to the fragmentation of the ancient Columbia supercontinent. Direct involvement in the research came from geologist Liam Courtney-Davies, who led the isotopic analysis while affiliated with Curtin University and is now based at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Mineralisation Linked to Supercontinent Cycles

Researchers attribute the iron enrichment to thermal and structural changes driven by continental breakup, which facilitated deep crustal reworking and fluid circulation. These conditions enabled the transformation of older banded iron formations (BIFs) into high-grade ore deposits with concentrations exceeding 60%.

This model reframes ore formation as a geodynamic process rather than a consequence of early biological or atmospheric changes. It also suggests a wider link between mineral systems and supercontinent cycles, a theory gaining traction among structural geologists and crustal evolution researchers.

Curtin University, a key institution involved in the research, has highlighted the implications for mineral exploration strategies in a press release on the discovery, calling it a possible turning point for identifying similar deposits in other regions.

By anchoring deposit formation to tectonic processes, the findings provide a new framework for exploration in other Proterozoic terranes across South Africa, Canada, and Brazil, where similar deep-crustal histories may exist.

Economic Scale and Exploration Significance

The deposit, estimated to contain 55 billion metric tonnes of ore, is one of the largest ever documented. Based on current iron ore prices, the total value exceeds $5.7 trillion, though researchers emphasise the scientific importance of the discovery over its commercial potential.

The Hamersley Basin, already central to Australia’s position as the world’s leading iron ore exporter, may gain further significance. According to Geoscience Australia, the country supplied over 35% of the world’s iron ore exports in 2022.

The study was funded by a collaborative group that includes the Australian Research Council, BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue Metals Group, and the Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia (MRIWA). Infrastructure support was provided through AuScope, a national geoscience network funded by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

Outstanding Questions in Regional Ore History

While the younger ore bodies have been firmly dated, earlier phases of mineralisation—believed to have occurred during the Palaeoproterozoic—remain difficult to evaluate. These earlier systems may have been eroded or overprinted by later tectonic events. Their potential contribution to iron enrichment is still under investigation.

Future research will likely focus on crustal thermal evolution between 1.4 and 1.1 billion years ago, especially the drivers of fluid flow and structural deformation responsible for the upgrading of iron-rich sediments. The techniques used in this study, including high-precision laser ablation ICP-MS methods, may soon be applied to re-examine other large ore provinces with unclear origins.

By refining the geological timeline of one of Earth’s most economically significant regions, the discovery reopens questions about the interplay between deep-time tectonics and modern resource distribution. Further data could extend this revision to other mineral systems shaped by the hidden architecture of ancient continents.

First Appeared on

Source link