Greenland Looks So Huge on Maps, Here’s the Distortion That’s Been Trickling Us All Along!

Greenland appears much larger than it actually is on most world maps, thanks to the Mercator projection, a centuries-old map style. A recent study reveals how this distortion influences our perception of the Arctic. This isn’t just a small detail, it affects how we view geography and even influence discussions about the Arctic. According to a study by Lieselot Lapon, a geographer at Ghent University, people’s perception of Greenland’s size can be dramatically off because of the Mercator projection.

Why Greenland Looks Huge on Most Maps

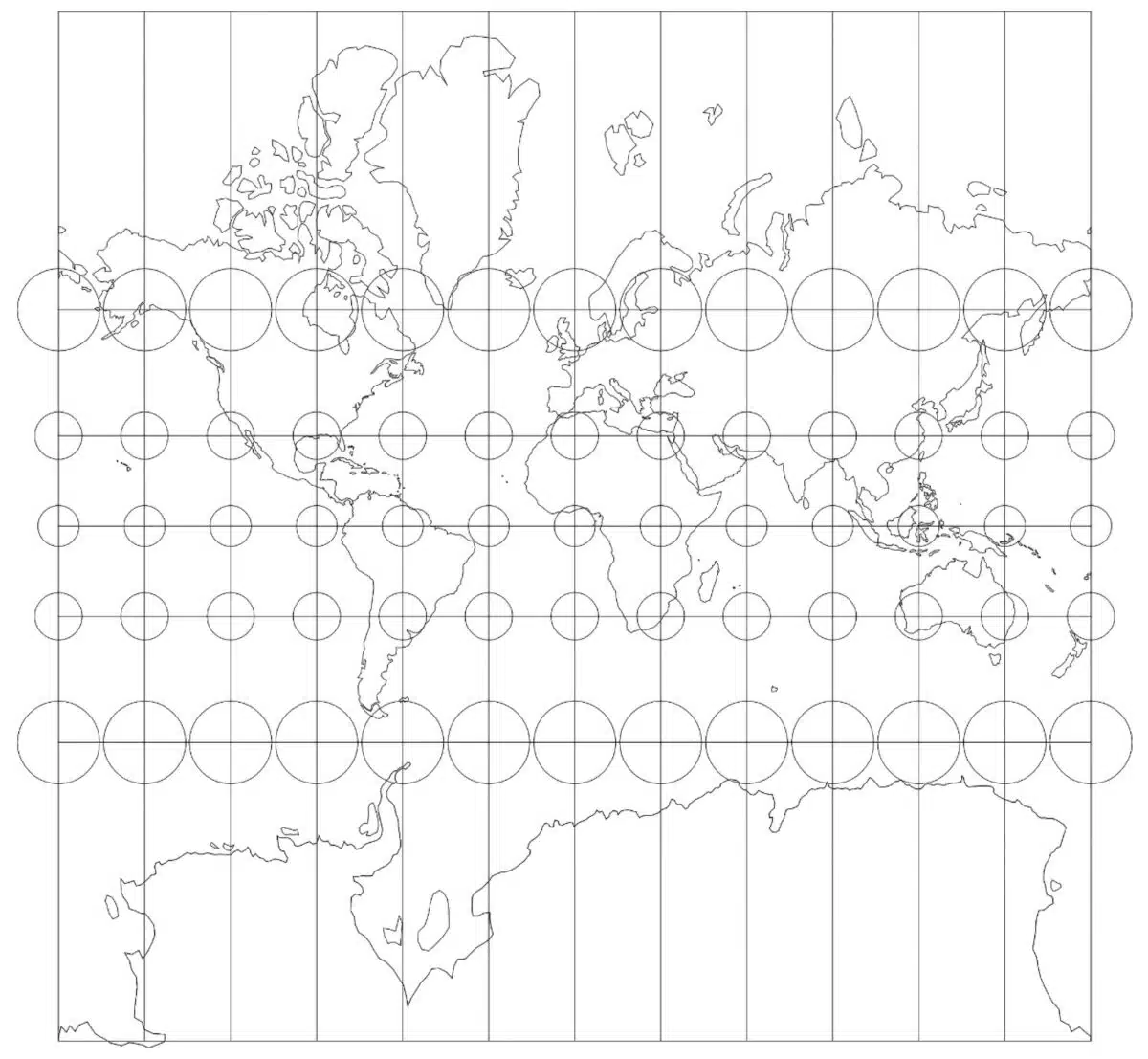

The Mercator projection, introduced in 1569, was created to help sailors navigate. By preserving angles and straight lines, it allowed ships to follow constant compass bearings across oceans. The trade-off was area distortion, which grows more severe toward the poles.

Landmasses at high latitudes are stretched dramatically. Greenland, positioned deep in the Arctic, is one of the most affected regions. On many maps, it appears comparable in size to entire continents closer to the equator.

A recent study led by Lieselot Lapon, a geographer at Ghent University, examined how this distortion influences public perception. Published in the ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, the research surveyed more than 130,000 participants and found a consistent pattern: most people significantly overestimate Greenland’s size.

Greenland vs. Africa: A Striking Illusion

The comparison between Greenland and Africa highlights the scale of the distortion. On Mercator-based maps, the two landmasses appear similar in size. In reality, the difference is vast. Greenland covers roughly 836,000 square miles. Africa spans about 11.7 million square miles, making it approximately 14 times larger. This visual inflation can subtly influence how people perceive geopolitical weight, natural resources, and environmental relevance.

Greenland holds strategic importance due to its Arctic location, mineral resources, and climate significance. Yet the projection exaggerates its spatial presence, potentially amplifying assumptions about its global role.

How Map Distortions Shape the World

Map distortions shape how we think about global issues. Greenland’s rapidly melting ice sheets, for example, are a major contributor to rising sea levels. According to NASA:

“They estimate that Greenland lost 3.8 trillion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2018 – enough to push global sea level up by 10.6 millimetres. Over the study period, the rate of ice loss was found to have increased seven-fold from 33 billion tonnes per year in the 1990s to 254 billion tonnes per year in the last decade”.

Online maps, including Google Maps, still use a version of the Mercator projection called Web Mercator. This variant is used because it’s simpler for digital maps, making zooming and scrolling easier. But it also keeps the same distortions, with Greenland still appearing much larger than it actually is. Google Maps switched to a globe view for desktop users in 2018, but the mobile version still uses the Mercator-style grid, continuing to mislead users about Greenland’s true size.

Moving Toward More Accurate Maps

Equal-area projections offer an alternative. They preserve proportional land size, though they may distort shapes. The Ghent University study found that people exposed to equal-area maps tend to develop a more accurate understanding of country sizes.

“The results indicate that the accuracy differs with the map projection but not to the extent that one’s global-scale cognitive map is a reflection of a particular map projection,” noted Lieselot Lapon.

No projection can preserve area, shape, distance, and direction perfectly at once. Every map involves compromise. Still, recognizing the distortion embedded in widely used projections invites a broader question: how much of what we think we know about the world is shaped by the way it is drawn?

Greenland’s strategic and environmental importance stands on its own. Yet seeing it at its true scale may help ground global conversations about the Arctic in clearer geographic reality.

First Appeared on

Source link