Half Pink. Half Colorless. Miners Discover a Massive 37.4-Carat Diamond with a Faultless Split Unlike Any Other Gem

A rough diamond unearthed in Botswana in the final quarter of 2025 has drawn sustained attention from geoscientists and gemological laboratories worldwide. The 37.41-carat crystal features a highly uncommon internal division: one half displays a vivid pink hue, the other remains entirely colorless. The stark planar boundary between the two zones is physically intact and free from blending.

This unique contrast in a single, uncut stone provides researchers with a physical record of differing conditions within Earth’s mantle, preserved in crystal form. Early-stage imaging has revealed lattice structures consistent with two distinct growth phases. The specimen remains under active analysis at a facility in Gaborone, where non-invasive testing is focused on mapping defect centers and internal stresses.

The diamond was recovered from the Karowe mine in northern Botswana. The site has become known for yielding exceptionally large and high-purity stones, including the 2,488-carat Motswedi diamond in 2024. Its geological setting, Archean cratonic crust coupled with deep kimberlite intrusions, makes it a reliable source of Type IIa diamonds, which contain extremely low concentrations of nitrogen and other impurities.

Laboratory Imaging Confirms Two-Stage Growth

Initial assessments by researchers at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) confirmed that the diamond is a Type IIa specimen. This classification, defined by its near-total chemical purity, makes such diamonds ideal for studying internal deformation and structural features. As reported by Earth.com, the pink portion of the crystal appears to have undergone plastic deformation, a permanent distortion of the atomic lattice under intense geological pressure.

Plastic deformation in diamonds alters the way light interacts with the crystal structure, producing pink coloration without the presence of foreign atoms. In this particular case, the deformation was sufficient to generate strong coloration, but not so extreme as to shift the hue toward brown. The other half of the stone, remaining colorless, likely grew under conditions with lower mechanical stress and no lattice distortion.

While other dual-color diamonds have been documented in laboratory archives, most weighed under two carats and showed partial transitions or irregular patterns. The Botswana diamond’s clear boundary, large size, and undamaged state present a rare opportunity for side-by-side comparisons of stress-induced and undistorted diamond growth in a single specimen.

Kimberlite’s Role in Preserving Deep Earth Structures

The diamond was transported to the surface through a kimberlite pipe, a geological process critical to preserving high-pressure minerals from deep within Earth’s mantle. Kimberlite pipes originate more than 150 kilometers below the surface during volatile-rich eruptions. These eruptions rapidly carry mantle material upward, limiting the opportunity for graphite conversion or thermal degradation of diamond crystals.

The nature and composition of kimberlite have long been associated with the concentration and preservation of diamond deposits. As outlined by Encyclopedia Britannica, kimberlite is a heavy, often fragmented igneous rock containing a mixture of olivine, pyrope garnet, phlogopite mica, and other high-pressure minerals. Its pipe-like structures penetrate ancient continental crust, offering a direct conduit from deep Earth to surface mining zones.

The boundary between the pink and colorless halves of the diamond is “sharp,” experts said. Credit: Wanling Tan/GIA

At the Karowe mine, processing systems have been designed to minimize breakage of large crystals. This technological approach, in combination with the site’s unique geological profile, allowed the 37-carat diamond to remain intact and available for laboratory analysis prior to any commercial cutting decisions.

Current testing includes spectroscopic imaging and photoluminescence mapping to characterize the distribution of lattice defects. These non-destructive methods allow researchers to observe internal features without altering the crystal, preserving its structure for continued study.

Structural Parallels With Argyle Mine and Supercontinent Breakup

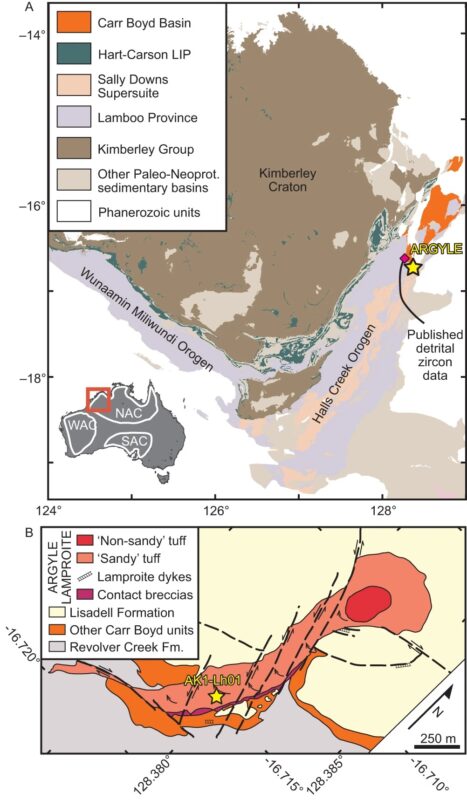

The two-phase formation of the Botswana diamond shares notable characteristics with pink diamonds extracted from the Argyle mine in Western Australia. A 2023 study published in Nature Communications presented evidence that tectonic deformation played a central role in creating the pink coloration found in Argyle stones.

Researchers dated Argyle’s lamproite host rocks to between 1311 and 1257 million years ago. These ages align with tectonic rifting linked to the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Nuna. The study used uranium-lead isotopic dating on minerals such as zircon and titanite to establish timing. Structural analysis of Argyle diamonds revealed internal lamellae, thin bands of deformation, that correspond with known tectonic activity during that period.

Although formed in a different cratonic setting, the Botswana specimen shows a similar pattern of plastic deformation followed by undistorted growth. The two halves of the diamond preserve contrasting geological histories, clearly divided by a flat internal boundary.

The GIA has confirmed that further structural and spectroscopic data will be released after the completion of imaging and classification work in mid-2026. The diamond remains uncut and is being preserved in its original form pending the conclusion of all ongoing analyses.

First Appeared on

Source link