He Disappeared Into a Cave for 63 Days Then Returned with a Scientific Breakthrough Still Changing Biology 60 Years Later

In July 1962, a young scientist entered a deep cave in the French Alps and disconnected entirely from clocks, sunlight, and human contact. He remained underground for 63 days. The effects on his body and brain went far beyond what he anticipated and helped launch a field that now shapes space exploration, military protocols, and medical science.

His name was Michel Siffre. The experiment was not sponsored by a university or agency. Yet the results continue to drive decisions at institutions like NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and multiple medical research centers.

The conditions Siffre imposed on himself, including near-total isolation, constant humidity, and the absence of all time cues, are difficult to recreate under today’s research ethics. In 2026, space agencies and chronobiology teams still reference his data when designing long-duration confinement studies.

How a Cave Experiment Proved the Body Keeps Its Own Time

Siffre conducted his isolation study in the Scarasson cave, located approximately 130 meters below the surface near the French–Italian border. Temperatures remained just above freezing, and the air was saturated with moisture. He used no watch and received no time updates from the surface, relying only on a phone line to report when he ate, slept, or woke.

When the surface team informed him that the experiment had ended, he believed he had spent only 35 days underground. In reality, he had remained there for 63.

In an interview with Scientific American, he recalled, “I lost all notion of time. I could tell if it was morning or evening, but that was it. I thought I’d been down there for 35 days. It had been 63.”

His internal cycle drifted away from the 24-hour norm. During a later study in Texas, supported by NASA, his sleep–wake cycles extended to 48 hours. These observations contributed early evidence that humans maintain an internal biological clock capable of running independently from environmental cues.

From Underground Science to Spaceflight Strategy

Though informal by modern standards, Siffre’s 1962 cave experiment received sustained attention from scientists and national space agencies. In 1972, NASA collaborated with him on a follow-up study in the United States designed to simulate isolation effects relevant to spaceflight.

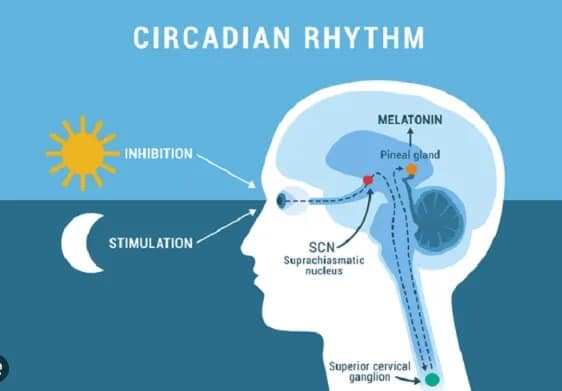

Independent studies by the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics and Harvard Medical School later confirmed that the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain’s hypothalamus functions as the primary circadian pacemaker. This structure coordinates internal rhythms including body temperature, hormone release, and sleep cycles.

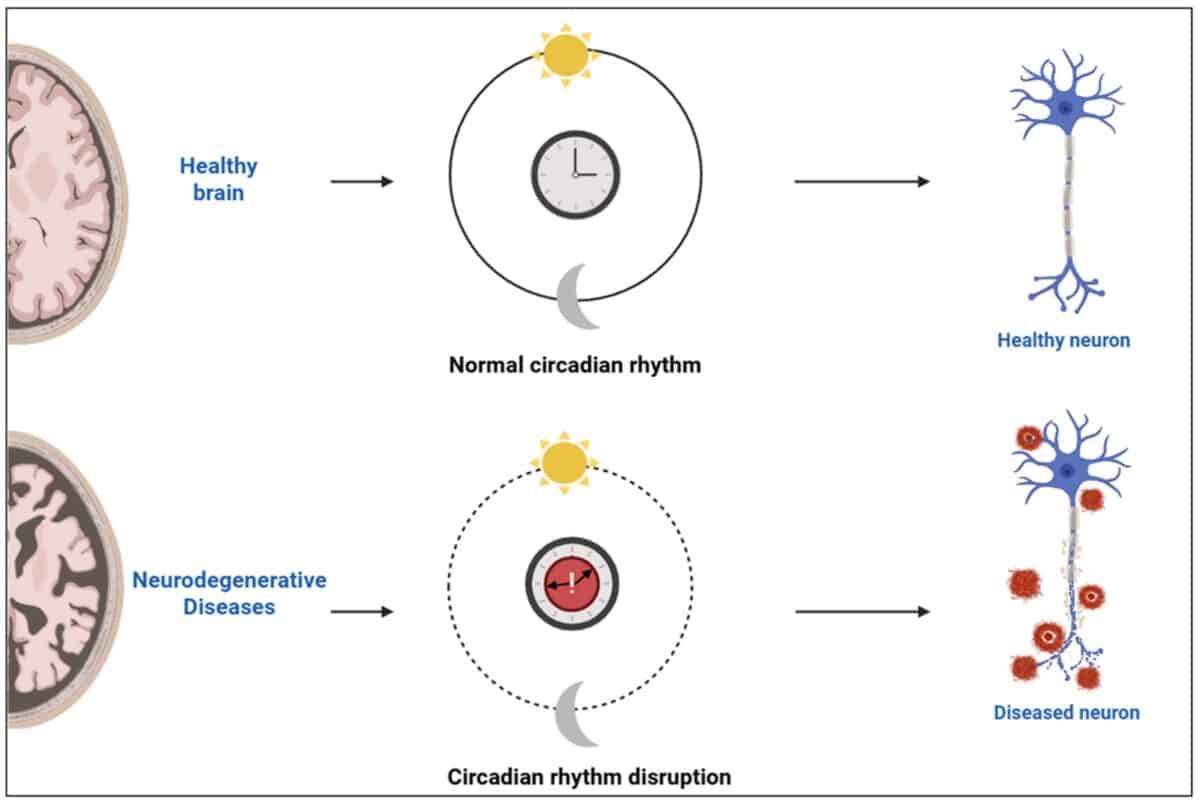

In 2020, a review published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience documented the relationship between circadian disruption and neurological conditions such as cognitive impairment, insomnia, and mood disorders.

ESA’s analog astronaut program also referenced Siffre’s data in the context of behavioral performance during Mars mission simulations. Analog environments attempt to replicate the isolation, confinement, and time deprivation expected during interplanetary travel.

Military planners also took note. During an interview with Cabinet magazine, Siffre recalled his work being used by the French Navy during the early stages of its nuclear submarine program. His findings informed scheduling approaches for submariners working in sealed, lightless conditions.

Extreme Sleep Cycles and What They Revealed

Other subjects in subsequent experiments, many conducted under Siffre’s supervision, displayed similar circadian disintegration. In one case, a participant remained asleep for more than 30 consecutive hours. Surface teams monitoring the study initially feared a medical emergency. Such extended sleep episodes were previously undocumented.

Modern isolation studies, though more advanced in instrumentation and oversight, continue to reflect Siffre’s core findings. Humans placed in environments without consistent external cues experience free-running biological cycles that deviate from the solar day.

Data from Siffre’s original experiments supported the development of spaceflight protocols for light exposure, task rotation, and recovery. In clinical research, these findings informed new strategies for improving the timing of treatment delivery based on circadian gene expression.

Chronotherapeutics has since become a formal research field. Medical trials in oncology, endocrinology, and sleep medicine are testing how the body’s internal clock can influence drug absorption and treatment efficacy. These efforts draw directly from early chronobiology experiments, including Siffre’s cave studies, which have been recently revisited in this analytical summary of their long-term impact.

Decades Later, the Data Still Shapes Human Systems Design

Siffre’s dataset remains one of the few long-term records of human physiology under natural isolation, collected outside a laboratory setting. His observations continue to influence system design and operational planning in space agencies, military operations, and extreme-environment research stations.

Circadian desynchronization is now recognized as a major concern for astronauts, remote researchers, and shift workers. Controlled light environments, melatonin protocols, and activity scheduling are being tested in analog missions and clinical settings worldwide.

As of early 2026, there are no internationally harmonized guidelines for managing biological time alignment in high-risk occupations, but several agencies are incorporating chronobiological standards into mission architecture and medical planning.

Unfortunately, Michel Siffre died in Nice, France, on 25 August 2024 at the age of 85 from pneumonia.

First Appeared on

Source link