Prices for next year’s Obamacare health insurance plans became public this week, with big increases in premiums across the country. We now have data that shows how much more people will pay.

Most people who buy their own coverage don’t pay full price. Tax credits created by the Affordable Care Act help pay the bills. But the new prices reflect what will happen if extra tax subsidies, first passed in 2021 and extended in 2022, are allowed to expire at the end of this year.

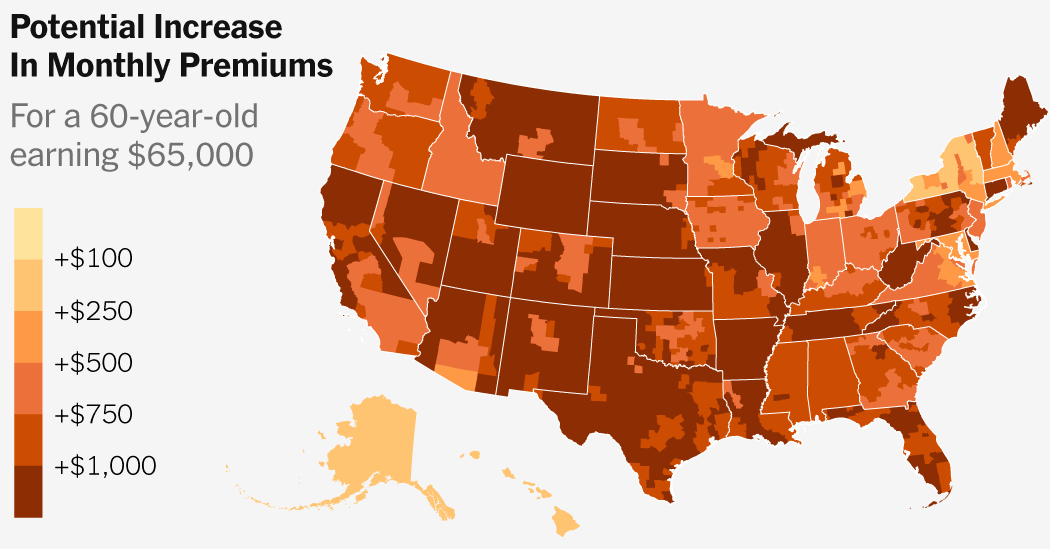

Change in 2026 monthly premiums without extra subsidies

The magnitude of the change depends on where people live, how old they are, and what they earn. (More details below.)

Extending the subsidies would cost the federal government around $23 billion next year and about $350 billion over the next decade, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office. Without them, many Americans will face much higher costs before the midterm elections next fall — in some cases increases of more than a thousand dollars per month.

This funding is at the heart of the congressional fight that has left the government shut down for nearly a month. Democrats have demanded an extension as a condition of their support for a government funding bill. Republicans have said they won’t consider an extension until the government is reopened.

The numbers in our charts and maps come from researchers at the health research group KFF, and reflect insurance prices published on healthcare.gov and state websites that allow people to “window shop” before Saturday, when insurance marketplaces will open for business. An earlier version of this article included estimated premiums for insurance next year, but now we can show the real prices Americans are currently facing.

Congress could still act and change the funding structure, but probably not before people start picking health plans this week.

For the lowest earners, free insurance could go away.

For people earning the lowest incomes, the expiration of the subsidies will mean the end of free, generous insurance. Right now, with the extra subsidies, eligible Americans who earn less than $24,000 a year don’t have to contribute money toward their premiums, though they still face some co-payments and deductibles when they use their insurance.

Monthly premiums for individuals earning $22,000

A single person earning $22,000, for example, will have to pay $66 a month for a typical plan after the subsidies expire.

Around half of all enrollees in Affordable Care Act marketplaces nationwide will experience increases in this range — from a free premium to one between $27 and $82 a month. This group includes many people close to the poverty line in states that didn’t expand their Medicaid program. Their insurance will remain heavily subsidized, just at the lower level established by the original Affordable Care Act legislation.

Although the price difference in dollars may look small, it can mean a lot for people who earn less than $2,000 a month. Since the enhanced subsidies became law, sign-ups in this lowest income group have tripled, with particularly large increases in Texas, Florida and Georgia. Some critics of the subsidies say the numbers have gotten so high that they are concerned about fraud.

People who earn a little more — $35,000 a year —are also facing relatively standard price increases around the country. Their cost for a typical plan will more than double without the extra subsidies, from $86 a month to $218 for a popular plan.

Monthly premiums for individuals earning $35,000

Around 40 percent of enrollees earn between $24,000 and $63,000 and will experience increases of this type.

For individuals who earn about $65,000, location matters, but age matters more.

Many older people at this income level will experience a sharp increase in premiums — from a few hundred dollars a month to $1,000 or more.

In most states, the enhanced subsidies created a ceiling on how much people earning more than $63,000 have to pay. Without the extra subsidies, people will have to pay whatever insurers in their markets charge. People in this group tend to be self-employed or work for small businesses.

Because insurers are allowed to charge higher prices to older customers than younger ones, subsidies for Americans at this income level make the biggest difference for people close to retirement age. The large increases in the underlying insurance premiums — around 26 percent on average for a typical plan — pile on top of the lost subsidies.

Monthly premiums for individuals earning $65,000

But where people live also matters. Premiums tend to be higher in rural areas, and they are particularly high in a handful of very rural states, like Wyoming and West Virginia.

For some people in the most expensive markets, the increases could be staggering. A 60-year-old living in southern Illinois will face premiums increasing from $460 a month with the subsidies to $2,800 a month without.

Increase in monthly premiums for individuals earning $65,000, if subsidies expire

Fewer than 10 percent of all Obamacare customers earn $65,000 or more.

For the top earners who receive subsidies, age matters the most.

People with even higher incomes have to pay a lot for Obamacare health insurance, with or without the extra subsidies.

Monthly premiums for individuals earning $95,000

Many younger people who earn this much haven’t seen any benefit from the extra subsidies. The subsidies kick in only when the cost of insurance is more than 8.5 percent of their income, which comes up only in the most expensive markets.

But some older people with high incomes do save money with the extra subsidies. Without them, they will pay even more than they already do.

This group is also affected by rising premiums. Even though the subsidies didn’t help many of them this year, they still paid lower premiums than insurers are offering in most markets for next year.

Increase in monthly premiums for individuals earning $95,000, if subsidies expire

Our charts and maps focus on how subsidies affect individuals buying insurance. The math is a bit more complicated for people who are buying insurance for their whole family. But the basic patterns are similar: Families at lower incomes would face more uniform increases, while families at higher incomes would see variable price increases, depending on where they live and the age of each family member.

You can estimate your personal household costs with and without the subsidies using this calculator from KFF.

About the data

The numbers in our analysis come from researchers at the health research group KFF and are calculated using insurance premiums published on healthcare.gov and state insurance marketplaces as part of “window shopping” for the 2026 plan year. An earlier version of this article was published using estimated price increases for 2026, and showed similar though not identical numbers.

Consumer costs are calculated based on the price of the “benchmark” silver plan in each market, the second-least expensive plan that covers around 70 percent of the average enrollee’s medical costs. Individual consumers may pay more or less if they choose other plans in the market. Calculations account only for federal tax credits and do not include additional state subsidies, available for some consumers in several states.

In a handful of states, people earning $22,000 won’t be immediately affected by subsidy changes because they qualify for different low-cost state insurance programs: Medicaid in Alaska, Hawaii and the District of Columbia; and the basic health plan in Minnesota, Oregon and New York (the basic health plan is Medicaid-like coverage with low premiums for a sliver of low-income Americans in certain states). New York residents earning $35,000 also currently qualify for the basic health plan.

The federal poverty level is higher in Alaska and Hawaii than in other states, which means the top income cutoff for subsidies in those states is higher than $63,000. That difference explains small differences in the average prices for people at $65,000 and $95,000 in income.

First Appeared on

Source link