Hidden ‘doomed’ star revealed by James Webb Space Telescope could solve decades-old mystery

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed a hidden “doomed” star that could help solve a giant astrophysical mystery.

The star is a massive red supergiant, which JWST snapped just before the star exploded in a fiery supernova. Massive red supergiants should, in theory, cause most supernovas, but they’re rarely observed. The latest JWST observation, described in a new study published Wednesday (Oct. 8) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, adds weight to the idea that these giants are often obscured by clouds of dust.

Stars around the size of our sun swell up near the end of their lifecycles to become red giants before going supernova. Red supergiants are massive stars on the verge of detonating, typically measuring hundreds or thousands of times larger than our sun.

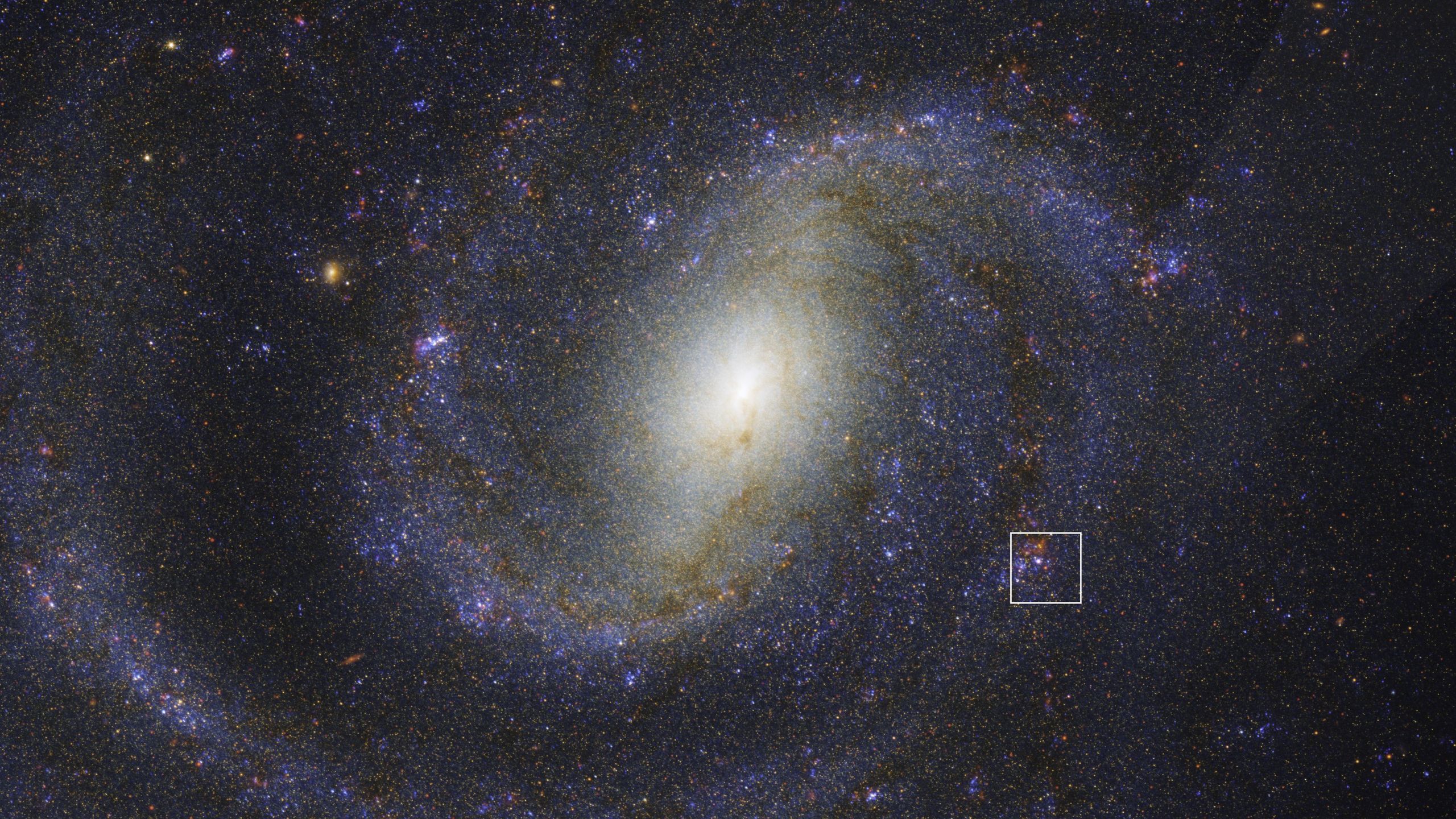

The All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae first detected the supernova from the newly imaged supergiant in June. The supernova, officially named SN 2025pht, came from a galaxy called NGC 1637, which is located 38 million light-years from Earth — pretty close for something in space. The authors of the new study identified the supergiant’s source star (its progenitor) by comparing historical Hubble Space Telescope data to new JWST images of NGC 1637 taken before and after the explosion.

Researchers like Kilpatrick have suggested that the most massive aging stars might also be the dustiest, so their light is blocked. This possible explanation tracks with the new JWST observation. The star shone about 100,000 times brighter than our sun, but the team estimated that its dust was so thick that this light was made more than 100 times dimmer, according to the statement.

The dust was also particularly effective at blocking shorter, blue wavelengths of light. Fortunately, JWST’s powerful infrared detection could see the longer red wavelengths, providing an unprecedented detailed look at a supergiant on the brink of going supernova.

“SN2025pht is surprising because it appeared much redder than almost any other red supergiant we’ve seen explode as a supernova,” Kilpatrick said. “That tells us that previous explosions might have been much more luminous than we thought because we didn’t have the same quality of infrared data that JWST can now provide.”

First Appeared on

Source link