How the harsh, icy world of Snowball Earth shaped life today

As Scotland’s west coast recedes from view, the ocean resembles a mirror, broken only by the swash of the boat and the dolphins chasing us. We’re headed to the craggy, uninhabited islands known as the Garvellachs. Only reachable during Scotland’s short summer, there is nothing between here and North America, and so landing – or rather jumping hopefully onto slippery rocks – is dependent on the kindness of the Atlantic swell. We’ve come to see a globally unique suite of rocks, which preserve a precise moment of global significance: when a warm, tropical environment, teeming with photosynthetic life-forms such as cyanobacteria and algae, transitioned abruptly into perpetual cold.

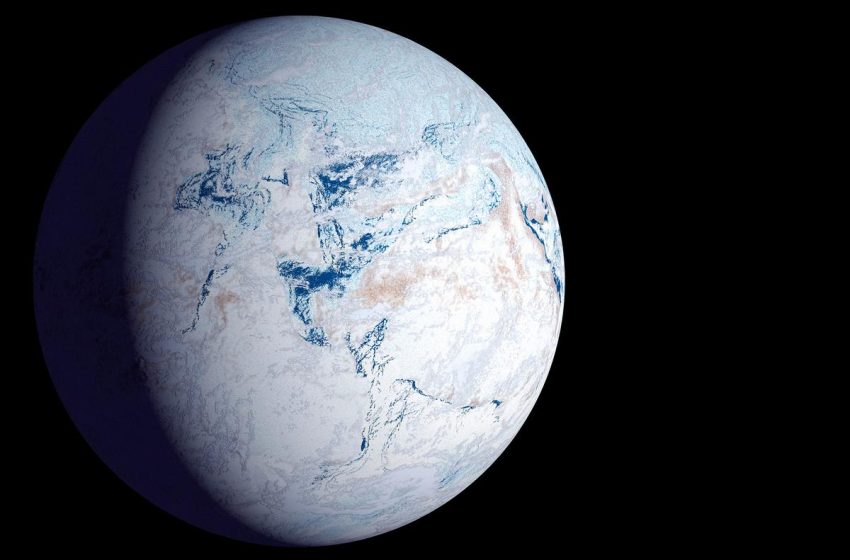

Imagine a planet suffocated by ice, its glaciers stretching unbroken from the poles to the equator. Such an event, if it transpired on Earth today, would see kilometres-thick ice sheets gouging their way from the Arctic to the Bahamas. Once-diverse ecosystems and climate zones would merge into a single, uniform condition, seemingly destined to be barren. Scientists once argued that such a ‘snowball’ state could never have existed on Earth since global glaciation could not be reversed. Moreover, on such a world, all life, including our own ancestors, would surely have been extinguished. However, hard evidence can change even the most fixed mind, and what was once inconceivable is now the prevailing wisdom. Today’s scientists agree that ice did indeed reach the equator on at least two occasions between 717 and 635 million years ago, where it stayed for tens of millions of years.

What’s more, I and many of my colleagues now think that life not only survived this frozen age, but that such extreme conditions may even have helped life become more complex, a process that would eventually lead to the evolution of all animal forms. Quite simply, without Snowball Earth, you and I wouldn’t be here. And embedded in the rocks of these remote Scottish islands, you can see how it happened.

Sedimentary layers transitioning into ice age on the Garvellachs in Scotland

For more than a century, geologists have been vexed by the apparent absence of a ‘long fuse’ to the Cambrian explosion of animal forms about half a billion years ago. Compared with the previous period, the Cambrian featured an astonishingly diverse array of creatures. How could biological complexity appear seemingly from nowhere? Often framed as ‘Darwin’s dilemma’, this enigma was a chief objection against the theory of evolution by natural selection, raised by sceptical geologists such as John Phillips in his book Life on Earth (1860), which he rushed to publication after Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). Although many pre-Cambrian fossils have been found subsequently, the abruptness of the Cambrian explosion is still somewhat of a mystery.

In Darwin’s day, few suspected that our planet may once have been covered by ice, and suspected even less that such conditions were pivotal in determining our own existence. To better understand any possible connection, we need to delve into what happened during Snowball Earth, or as we geologists like to say: the Cryogenian period. Part of the Proterozoic aeon, this was one of the last periods before the Cambrian began.

I have spent much of my career examining the physical evidence for how our planet looked during Cryogenian times, evidence that is etched into the rocks beneath our feet. Over three decades, I have asked questions such as: how long did the ice age last, was it truly global in extent, and what were the consequences for life? Most recently, my attention has turned to the Garvellach islands in Scotland, an archipelago I studied as an undergraduate, but somewhere I hadn’t revisited until the COVID-19 pandemic prevented any globetrotting.

The rocks bear witness to the exact moment when the tropics first succumbed to the encroaching deep freeze

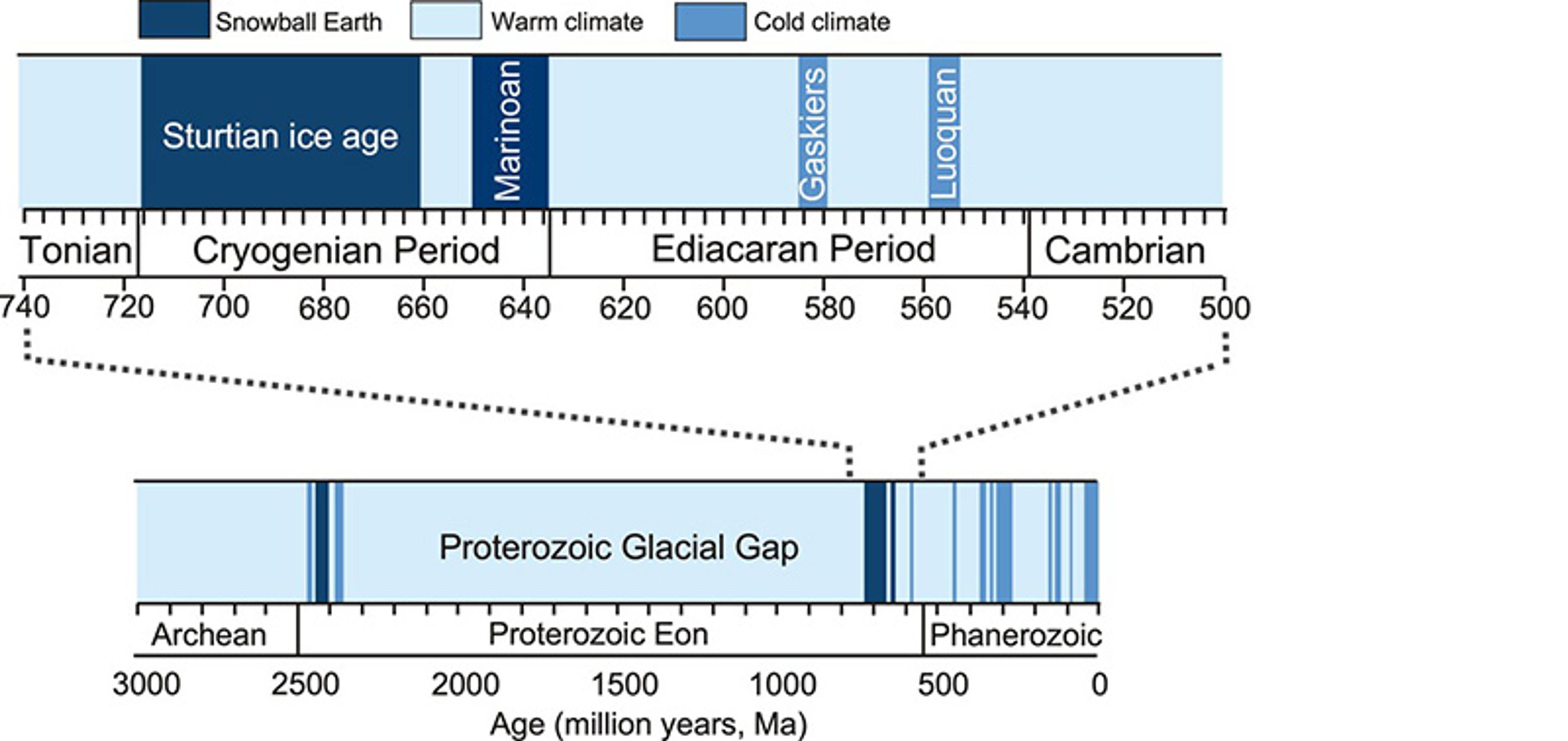

Studying the Garvellach outcrops has confirmed what had long been suspected: that a remarkable set of rocks spanning Ireland and Scotland – the Port Askaig formation – is likely to preserve the world’s most complete record of Snowball Earth, and most critically the moment it all began. The first of the Cryogenian ice ages, the Sturtian, began around 717 million years ago, and lasted everywhere on Earth for another 57 million frigid years. A second glaciation, called the Marinoan ice age, lasted from about 645 to 635 million years ago, and marks the end of the Cryogenian. Both episodes saw glaciers reach the equator.

Glacial deformation in lithified moraines (left); rock layers contorted by the weight of glaciers (right)

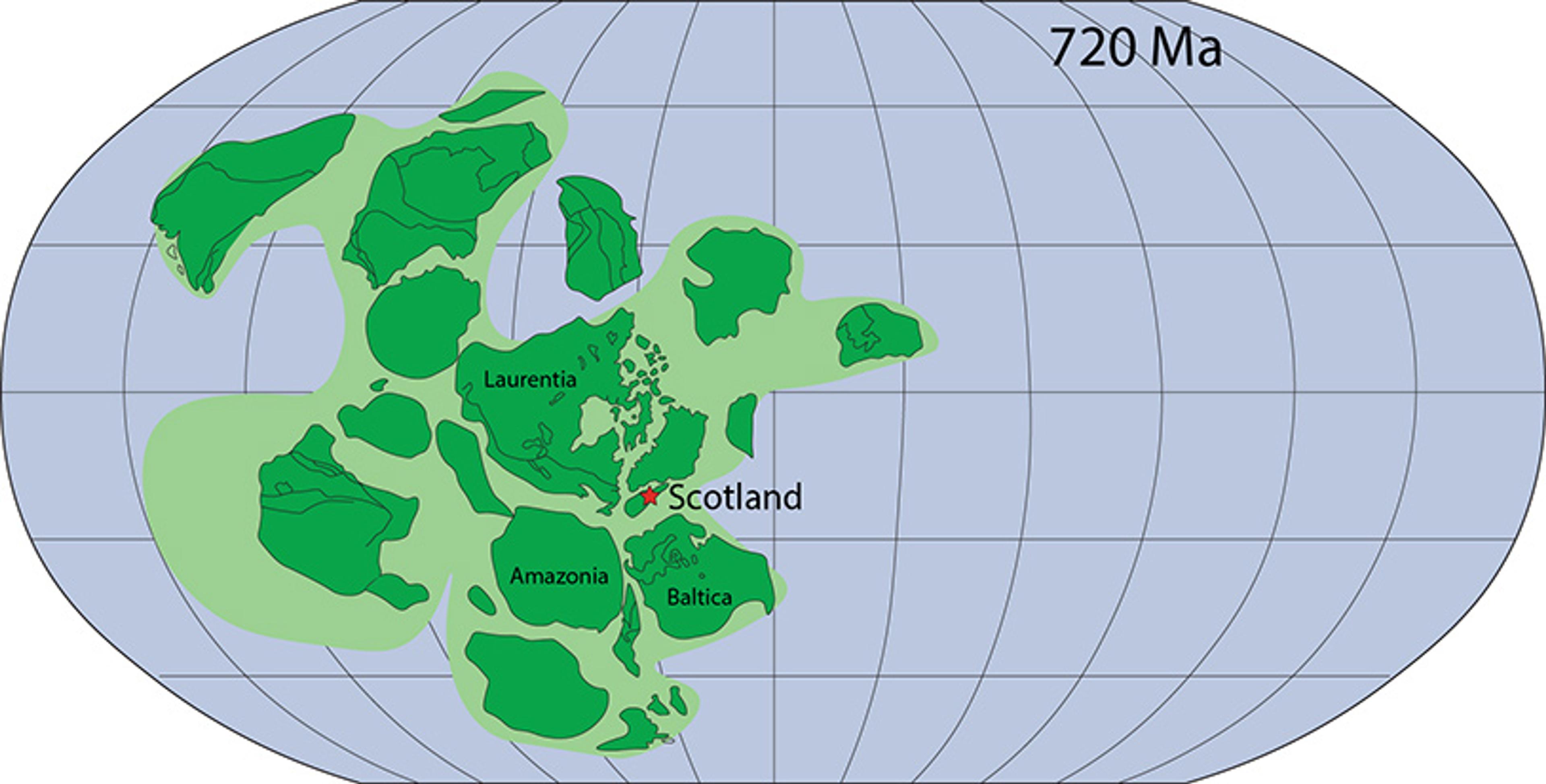

Unlike other sites where the erosive power of ancient glaciers scraped away crucial evidence, in Scotland the rocks bear witness to the exact moment when the tropics first succumbed to the encroaching deep freeze. This is because, back then, Scotland was at far lower latitudes than today due to continental drift. Also, the sedimentary layers are exceptionally well preserved. Only here can we walk step-by-step through almost 80 metres of rock layers that represent the slow passage of time and changing climate from balmy shores to glacial wasteland.

Early signs of cooling can be seen in the increasing numbers of isolated ‘dropstones’ and gravel clusters, which must have fallen from passing icebergs that drifted ahead of the expanding ice caps. The appearance of frost-shattered ground reveals an increasingly frigid and arid environment that eventually gave way, first to glaciers, and then to towering ice sheets. Some were so massive, up to several kilometres in thickness, that they carried with them rock debris as large as football fields, gouged out from the underlying carbonate platform. The best example, the ‘Bubble’, is a huge chunk of white carbonate rock, which now sits in a porridge of smaller fragments. The layers that once marked out the horizontal seafloor have been so contorted during glacial transport that they now look skyward, having been folded in on themselves as if solid rock were putty. A modern analogy would be if Australia’s Great Barrier Reef were to be lifted out from the sea, only to be kneaded deep inside marauding Antarctic ice sheets.

The ‘Bubble’ on the Garvellach islands

The harshness of the wild seas here never kept people away from the now-uninhabited Garvellachs. On returning from travels that had taken him right across the Atlantic Ocean, Saint Brendan, one of the most famous navigators of all, even founded a monastery on the islands in the 6th century. Beehive huts, or clochán – meditative igloo-shaped structures of stone flags, made by generations of monks since the time of Columba – can still be seen on Eileach an Naoimh, which some call Holy Isle. The craggy walls of these huts are all made up of lithified glacial moraine, ancient remnants of Snowball Earth. The extraordinary ‘Bubble’ must have been contemplated by myriad travellers over many centuries without any inkling about its significance.

The completeness of the sedimentary record on the Garvellach islands has another significance, in that it makes them an excellent candidate for defining the beginning of a new geological period. Such decisions are made only rarely, and only after years of discussion among geologists. Once ratified by the International Union of Geological Sciences, a global boundary stratotype section and point (GSSP) can be established. Informally, these GSSPs are called ‘golden spikes’, as decorative metal plates are ceremoniously hammered into rock outcrops whenever a particular locality is declared the global standard. Not all make the cut though: a proposed GSSP for the Anthropocene, in Canada, was recently rejected.

The end of the Cryogenian already has a GSSP, to mark the start of the Ediacaran, a time renowned for many discoveries of early animal fossils. However, the beginning does not yet have its own golden spike. The Cryogenian GSSP is set to be voted on during the course of 2026, and would represent the transition into about 70 million years of icy cold, punctuated by just one, relatively short interval of warmth.

Beginning 720 million years ago, the Cryogenian period was punctuated by two plunges into the deep freeze, commonly referred to as Snowball Earth. Did these extreme conditions shape the evolution of life?

How did this deep freeze happen? This was undoubtedly an extraordinary moment in geological time, and extraordinary phenomena require extraordinary explanations. One of these involves the unusual arrangement of continents around this time, and goes as follows.

Sediments began pouring in as Rodinia first bulged upward, and then ruptured to form a new ocean basin

Across our planet’s history, tectonic plates have collided to form supercontinents. Before the Cryogenian, a single supercontinent called Rodinia assembled piece by piece. Eventually, however, Rodinia had become a vast, arid land mass, resembling a supersized Australia, having been denuded by aeons of weathering and erosion. Mountain belts would have been low and scarce during this relatively quiet time for the planet, so quiet in fact that some dub this interval the ‘boring billion’. But all this was about to change. Rodinia was poised to break apart, its bulging interior marking the sites where volcanoes would burst through, giving birth to embryonic oceans and the beginning of a new supercontinent cycle.

Around 720 million years ago, the supercontinent Rodinia was beginning to break up, coinciding with the start of Snowball Earth

Shortly before ice sheets enveloped the planet, Scotland sat at the margins of a landmass called Laurentia, near Rodinia’s edge. This meant it was greatly affected by the subduction of tectonic plates beneath the supercontinent’s margin. We can recognise this destructive tectonic setting by the types of rocks and minerals that form the sedimentary layers beneath the glacial horizon in Scotland and Ireland. Following glaciation, sediments began pouring in as Rodinia first bulged upward, and then ruptured to form a new ocean basin. Before oceans are born, magma rises from below to fill underground chambers and eventually volcanoes. Volcanic rocks across North America – also once part of Laurentia – witness this turbulent history. And, crucially, they can be dated to show that this ‘rifting’ began only a million years or so before glaciation. This is a critical, although circumstantial, piece of evidence to show that rifting may have triggered cooling, because while volcanoes belch out greenhouse gases, such effects are short-lived compared with the cooling that occurs when extruded lavas are weathered. The chemical weathering of fresh lava is known to soak up atmospheric carbon dioxide, which is why sprinkling powdered basalt across farmland could help reduce global warming. The notion that basalt weathering caused Snowball Earth is often referred to as the ‘fire and ice’ hypothesis.

Although plausible, there is a significant problem with the fire-and-ice model. Other supercontinents, such as the more recent Pangaea, also broke up, but that did not lead to glaciation. If supercontinent breakup triggered Snowball Earth, then why did it happen only once? There must be something more to the story.

Snowball Earth is so unusual an event that it challenges the uniformitarian mantra that has been hardwired into geologists’ minds ever since the days of Darwin and Charles Lyell. Students are still taught that ‘the present is the key to the past’, only to later discover that it doesn’t always apply, and that it might sometimes be better to adopt a livelier imagination. If we could journey back to our ancestors’ most formative years, and witness the first animals coming into being, we would find a planet as alien to us as Mars is today. The Cryogenian, and the Ediacaran that immediately follows, simply do not conform to our current understanding of how the Earth system works.

Consider the atmosphere. The Cryogenian and Ediacaran witnessed considerable climatic instability, likely driven by very high atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations followed by equally extreme low points, leading often to glaciation. Such oscillatory behaviour suggests uniquely strong, positive feedbacks unlike anything Earth experienced before or since. Perhaps this instability reveals the secret behind the cold climatic malaise of Snowball Earth. Back then, a gentle push in one direction could lead to runaway cooling or warming. Any negative feedbacks, such as those that stabilise climate today, must have been so weak that glaciation sometimes set in too hard before they were able to kick in.

Scotland’s carbon isotope record falls perfectly into this emerging paradigm. As carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and buried as isotopically light organic matter, the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 increases in the oceans, and this isotopically heavy signature can be recorded in sedimentary rocks as a sign of global cooling. Conversely, if organic matter escapes burial, carbon dioxide can rise to higher levels, leading to global warming. Over the previous decade, it has become increasingly clear that ancient glaciations were preceded by extremely warm climates: so warm even that almost no organic matter could be buried anywhere on Earth. This is because organic decay scales exponentially with temperature. If no organic matter can be buried, then the greenhouse effect raises temperatures ever higher. This is a classic positive feedback: higher temperatures mean less burial, which in turn leads to higher temperatures. Isotopic oscillations indicate strongly that glaciations arose when conditions shifted towards greater organic burial, evidenced by increasingly ‘heavy’ sedimentary carbon.

Life had to survive a deep freeze and the extreme hothouse conditions before and after each icy plunge

By analysing the carbon isotopes of the Garvellachs rocks, we can see this transition playing out, as the return to isotopically heavy carbon coincides exactly with the first sedimentary evidence of cooling. Unsurprisingly, it is this precise sedimentary layer that is being proposed as the golden spike to mark the official start of the Cryogenian globally. The breakup of Rodinia may well have been the catalyst to cooling, but it was the bizarrely unstable nature of the Earth system that caused the event to have such dramatic consequences.

So what did such oscillations mean for life? Life, which had thrived on the ocean’s margins up to this point, had to survive not only through a deep freeze, but also the extreme hothouse conditions before and after each icy plunge. Like ancient Romans stepping between the frigidarium and the caldarium, lifeforms needed to negotiate repeated shocks to the system, producing a succession of bottlenecks that not only sped up the rate of evolutionary change but critically determined who would survive to become our early ancestors.

It is only in the past few years that we’ve realised that climatic extremes characterise the entire interval from the Cryogenian right the way through to the Cambrian explosion, and that the Snowball Earth interval represents just the two most extreme and prolonged examples of global cooling. Crucially, changes in organic burial would not only have perturbed climate, but also affected oxygen availability, because organic burial allows the oxygen released by photosynthesis to remain in the atmosphere. It seems likely therefore that oxygen levels also fluctuated wildly throughout those eventful times, causing booms and busts for life on Earth. Oxygen is important for all metabolically energetic animals that build energy-sapping skeletons, muscles and organs. Without oxygen, no creature can move, grow large or even think. It is highly significant therefore that the Cryogenian separates a world with only single-celled protists before, from the more complex multicellularity exhibited by true animals after global glaciation.

Although the extremes of climate, oxygen and environment that typify this interval can potentially explain biological diversification via repeated radiations and extinctions, they don’t really explain why the road to greater complexity became the chosen path, especially considering the billion years of remarkably little progress beforehand. So let’s now return to the question posed earlier: how did Snowball Earth favour the emergence of complex life?

Profound glaciation, although presumably a shock for life accustomed to tropical climes, would, once established, quickly have become the norm. Whatever lived on Earth through those times would have ended up well-adapted to extreme cold and dryness. Although fossil assemblages are fairly nondescript during most of the Cryogenian, we know that many types of organisms still alive today survived somewhere, even if we do not know where. One thing we have learned in recent years, though, is that an entirely glaciated planet need not be lifeless.

Although we often think of ice caps as barren wastelands, this is untrue. Many organisms that specialise in slow reproduction live in isolated oases on top of the ice. Cryoconite holes are a good example. They form when windblown debris, such as volcanic ash, absorbs heat from the Sun to melt a small patch of ice, which then acts as a tiny, isolated refuge for a surprising diversity of lifeforms. Today, cryoconite holes provide homes for all the major groups of life: bacteria, algae and eukaryotes, including protists that ingest organic matter, and several invertebrate animal phyla, dominated by the hardy water bears (tardigrades) and rotifers. Fossilised amoebae-like protists that would become the cousins of all animals appeared just before the onset of the Sturtian ice age, and so must have lived through all of the Cryogenian. Yet fossil evidence may never be found as it has melted away.

Cryoconite hole. Courtesy of Wikimedia

Organisms with surprising complexity likely existed before the ice. Although we animals possess the most intricately interconnected organs, we are not the only creatures to demonstrate multicellularity. Even single-celled life forms, such as bacteria, can form colonies of millions of identical cells. Moreover, cell differentiation is also not unique to us and likely arose more than once in Earth’s history: in land plants (embryophytes), green algae (chlorophytes), red algae (rhodophytes), brown algae (heterokontophytes) and at least twice in fungi. Amazingly, several of these groups existed well before the Cryogenian. Indeed, some groups of fungi, green and red algae, as well as the above-mentioned amoebae all made it through Snowball Earth unscathed, as pre-glacial fossils are commonly identical to their living relatives. Not only that, but molecular evidence shows that algae, as well as our animal ancestors, diversified both during and shortly after the Cryogenian. This was truly a period of extraordinarily radical and rapid evolutionary change, characterised by complexification.

Did Snowball Earth make cell cooperation a more viable option than, say, a return to an independent single-celled existence?

Rather than being an evolutionary dead end, the Cryogenian, and specifically the Snowball Earth event, seems to have been the catalyst that paved the way to modern ecosystems. The emergence of complex multicellularity in the aftermath of Snowball Earth laid the foundations for the diverse and interconnected web of life that shapes our planet’s ecosystems today.

Some mysteries do still remain, though. In multicellular animals, individual cells have to make sacrifices for the good of the whole, and in many cases cells are even prohibited from growing at the expense of the organism. In order to achieve such apparent altruism, labour must be divided, sufficient resources allocated and suitable environments maintained, just like in any well-managed city. Did Snowball Earth make cell cooperation a more viable option than, say, a return to an independent single-celled existence or to a simpler, colonial form of multicellularity? In this, the jury is still very much out, but perhaps slime moulds can lend some insight.

The spontaneous development of multicellularity in normally single-celled protists is thought to be a response to sudden, unfavourable conditions. In the life cycle of cellular slime moulds, for example, which can today be found in both Arctic and Antarctic realms, initially identical cells huddle together as a colony to form a multicellular slug that then proceeds to crawl to the light. The slug soon turns into a fruiting body before expelling its spores to start new colonies elsewhere. Some cells even appear to sacrifice themselves to become a woody stalk, all for the good of the whole. This seemingly animal-like behaviour would be a great strategy to ensure survival in harsh, isolated ecosystems, starved of nutrients. In such slugs, may we be glimpsing those very first steps towards our own animal ancestors? Could it be a similar kind of creature that clung to the ice during its Snowball period?

Frost-cracked moraine on the Garvellach islands

Returning from the Garvellach islands, tired from a day’s rock hammering, and salty from the sea spray, my colleagues and I find time to reflect upon how this incredible transition into glaciation, 717 million years ago, was so much more than simply an unusual climatic event. Wild swings between hot and cold, oxygen-replete and oxygen-starved conditions over many millions of years, heralded a biological revolution that redrew the tree of life. Greater cooperation between cells eventually led to more energetic, oxygen-sapping metabolisms, and the arms race that became the Cambrian explosion.

Walking along the rocky shoreline allows us to step, rock bed by rock bed, through 70 million years of time, when life was forced to adapt to extreme cold. Although icy conditions fostered the gradual emergence of biological complexity, it was the thaw that likely proved the most pivotal. Walk along the coast hereabouts and, abruptly, the rocks change: no evidence of ice can be detected here, or indeed anywhere on Earth 635 million years ago. We have reached the start of the Ediacaran. The catastrophic retreat of the ice sheets and unprecedented sea-level rise, happening swiftly over mere thousands of years, launched a fight for survival in a rapidly warming, oxygenated world. The ancestors of you, me and all our animal cousins must have won that race.

First Appeared on

Source link