How tumours trick the brain into shutting down cancer-fighting cells

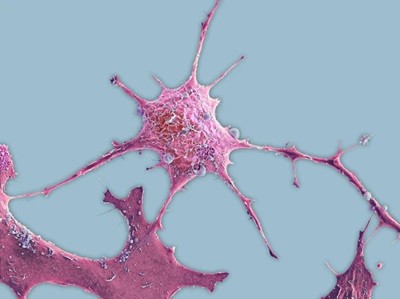

Lung cancer cells (shown) in mice can connect with nearby neurons to send a ‘shutdown’ signal to the brain that suppresses tumour-killing immune cells.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Tumours boost their own growth by attracting and then commandeering nearby sensory neurons, a study finds. By ‘plugging into’ tumour cells, these neurons can send a signal to the brain that subdues the protective activity of immune cells at the tumour site — allowing the cancerous cells to proliferate unchecked.

Breast-cancer cells enlist nerves to spread throughout the body

The study, published today in Nature1, pinpointed this signalling pathway, from the tumour to the brain and back again, in mice with lung cancer. “The tumour hijacks the signalling axis and uses it for its own purpose,” says Anna-Maria Globig, a cancer immunologist at the Allen Institute for Immunology in Seattle, Washington.

When the authors of the study used genetic engineering to inactivate, or ‘knock out’, the sensory neurons, they “saw such a huge, dramatic reduction” in tumour growth — more than 50% — says co-author Chengcheng Jin, a cancer immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Making a connection

Researchers have long known that nerve cells reside in tumours. “We know that nerves are there,” says Moran Amit, a head and neck surgeon at the University of Texas in Houston. But working out how these nerve cells affect a tumour’s survival has been difficult, he adds.

How cancer hijacks the nervous system to grow and spread

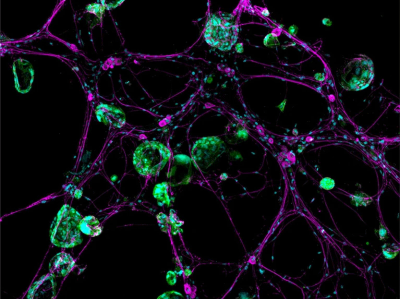

One reason is that genetic tools haven’t always been sophisticated enough to precisely analyze neurons’ activity. Another is that neurons are the body’s longest cells; their DNA and RNA are mostly stored in cell bodies that sit far away from the fibre-like tendrils, called dendrites, that plug into tumours. So it is hard for researchers to collect much genetic information about the neurons during tumour biopsies. The peripheral nervous system is “the last area that really wasn’t being studied” in the context of cancer, says Timothy Wang, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University in New York City.

Jin and her colleagues, who had microscopy data showing neurons surrounding and penetrating lung tumours, hoped to make progress by inactivating certain neurons, either with genetic techniques or drugs, and observing the effects on cancer growth. “We took almost a year trying different drugs,” says co-author Haohan Wei, a cell biologist also at the University of Pennsylvania. “There wasn’t any effect.”

First Appeared on

Source link