Inside the $22 trillion world of private capital, an asset class so big it would be the world’s second-largest economy

Top analysts at Bank of America Research are pulling back the curtain on the colossal $22 trillion universe of private capital, an asset class so massive it would be “the world’s second-largest economy” if it were treated as a country. As the global financial landscape faces tectonic shifts, Bank of America Research’s latest thematic investing report reveals that private capital is reshaping how companies, investors, and economies think about growth, risk, and control, challenging the primacy of public markets and opening new frontiers for both innovation and caution.

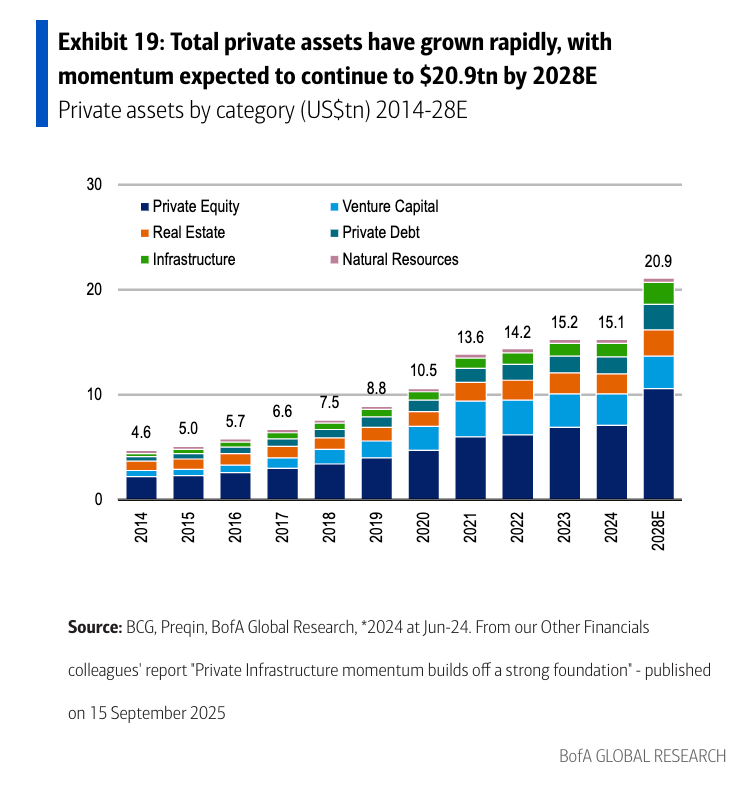

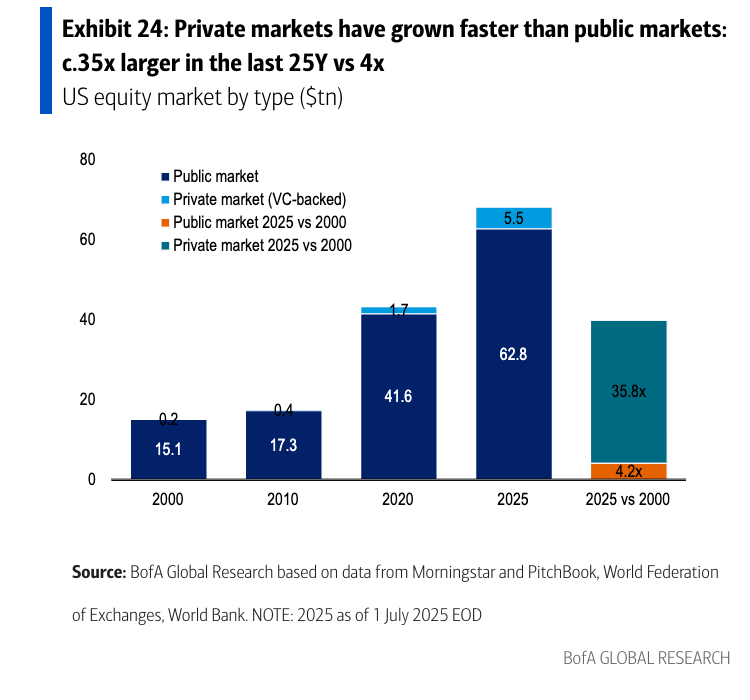

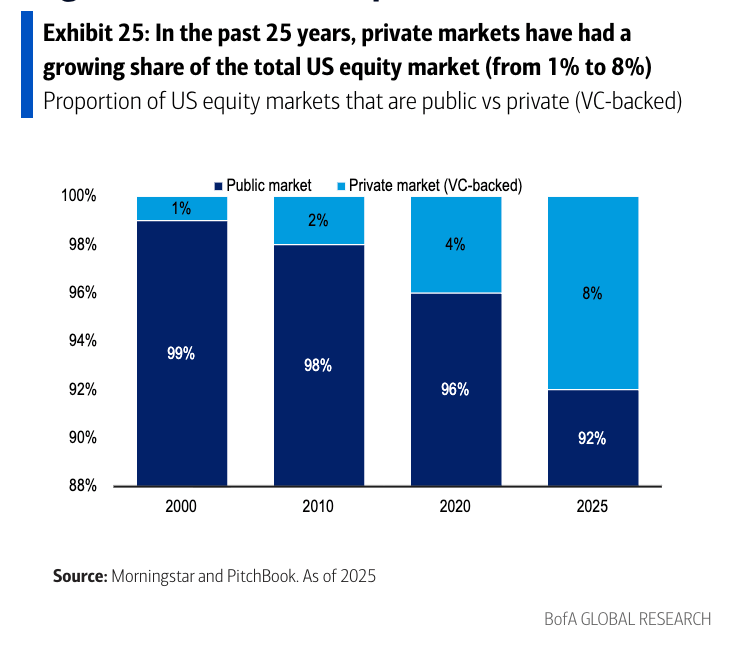

Private capital, defined by the bank as assets not available on public markets, includes private equity, private credit and real assets. It has multiplied at a staggering pace, more than doubling since 2012 to $22 trillion by 2024. This explosion has been driven by a retreat from public markets. Since 2000, the number of U.S.-listed companies has halved to just over 4,000, even as the number of private venture-backed firms soared 25-fold. Startups now remain private for an average of 16 years, a third longer than a decade ago, reflecting a broad shift toward private capital and away from public scrutiny and regulation.

The world’s most transformative firms aren’t found on the stock market ticker, BofA argues. Just as public stock markets have a “Magnificent 7,” so there is a “Private Magnificent 7” of “hectocorns,” each valued at $100 billion or more and growing. BofA’s Thematic Research team estimates that their combined valuations have skyrocketed nearly fivefold since 2023 to $1.4 trillion. They evaluated the top 16 companies in the space, representing $1.5 trillion in value, an astonishing 1% of global GDP. There are many other “decacorns” (valued at $10 billion+) and unicorns below them in the list.

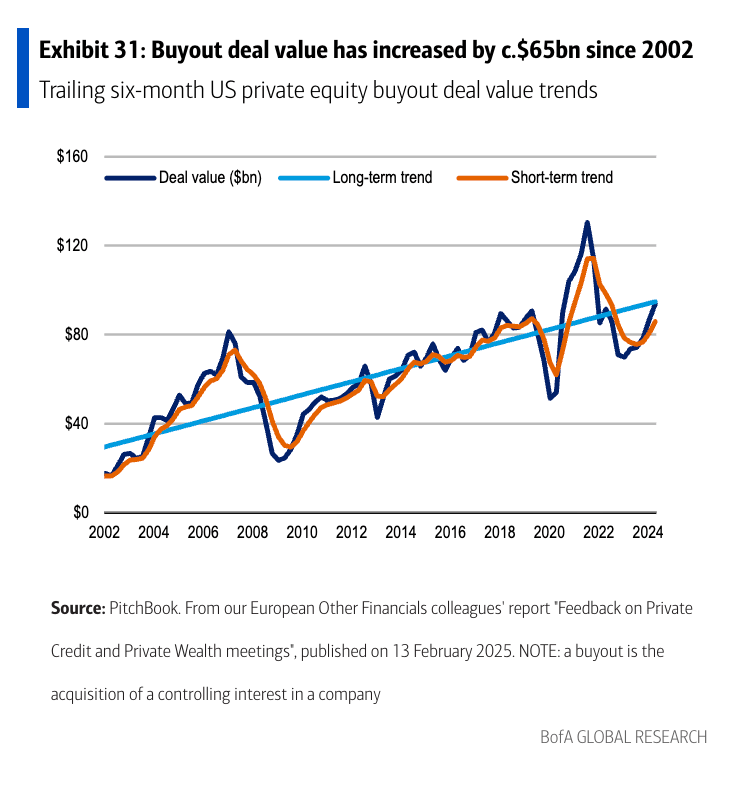

For investors, BofA finds that private equity has notably outperformed the S&P 500 over this period, by six percentage points per year on average. And there are other benefits to privacy, BofA analysts add: “In the time spent on financial regulation paperwork every year, 12 Great Pyramids of Giza could be built.”

But as this asset class balloons, financial experts warn that opacity breeds risk, especially with regard to the $1 trillion-$3 trillion chunk of the asset class known as private credit. Public markets offer transparency, governance, and liquidity; private firms, by contrast, often avoid periodic reporting and undergo less rigorous oversight. This lack of visibility can mask financial and governance hazards, with analysts urging investors not to overlook the pitfalls in their quest for returns.

Wall Street’s “fear index”—the VIX—spiked by more than 35% in the past month amid bankruptcies at subprime lender Tricolor Holdings and auto supplier First Brands, both marred by alleged fraud and loss events, slicing $100 billion off U.S. bank stock market capitalization. JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon warned, “When you see one cockroach, there are probably more,” pointing to the dangers of hidden risks in private lending markets. In fact, Dimon has been sounding a similar tune since at least May, when he warned that non-bank lending “hasn’t been tested in a downturn,” implying that a deluge of defaults could follow if a recession hits.

Capital allocation goes private

Historically, public companies were seen as the best vehicles for capital efficiency. They offered liquid investments, transparent financials, and were accessible to all. Yet, private capital is rewriting the rules. With fewer companies pursuing IPOs, public markets are losing their once-central role in economic growth. At the same time, innovation and digitization—sparked by disruptors like OpenAI’s ChatGPT—are increasingly nourished by deep-pocketed private investors. Since ChatGPT’s launch, BofA finds, Nvidia, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have invested in roughly half of the world’s 100 artificial intelligence (AI) unicorns.

The data-center deals that are driving a significant chunk of GDP growth are increasingly based on private credit, to boot. Meta, for example, has secured a nearly $30 billion financing package or a data center in Louisiana, Bloomberg reported, adding that it is the largest private capital deal on record. The scale of spending in this space is unprecedented, with OpenAI alone estimating it will require trillions in infrastructure spend to keep up with rapid technological demands. In late October, Apollo Global Management Chief Economist Torsten Slok argued that private construction spending on data centers was so massive that there was “basically no growth in corporate capex outside of AI at this moment.”

Even some of the beneficiaries of this are concerned. OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman has drawn parallels to the dot-com bubble, cautioning that “someone’s gonna get burned there”—especially since 95% of generative AI projects reportedly don’t deliver any profit, according to a widely read piece of MIT research. Analysts warn that investors could face pain if speculative infrastructure bets outpace real-world utility or revenues, recalling lessons from early-2000s telecom overreach.

The first phase of AI build-out was largely peer-to-peer, but now bond investors and private credit lenders are providing two to three times the funding of public markets. Tech “hyperscalers” have tapped private credit for sustained, long-tenor loans, and commercial mortgage-backed securities tied to AI infrastructure hit $15.6 billion in August, JPMorgan estimated at the time. Major deals now feature 20-30 year funding horizons—extraordinary bets on technologies whose commercial viability five years from now remains uncertain. “We are conservative in our assessment of forward cash flows because we don’t know what they will look like, there’s no historical basis,” Ruth Yang, global head of private market analytics at S&P Global Ratings, told Bloomberg in August.

Shawn Tully, who has reported extensively on private credit for Fortune, noted a distinction between major players such as Apollo, Ares, and KKR, who are “pioneering a highly original strategy by extending credit they originate independently, often backed by high-earning assets from rail cars to data centers, that lock in borrowers for a number of years.” Borrowers are willing to pay a lot more in interest than the traditional lengthy, expensive syndication process that requires ratings from S&P and Fitch, tough covenants, and sometimes long.

Two top executives in the space, David Spreng of Runway Growth Capital and Ted Goldthorpe of BC Partners Credit, argued in a Fortune commentary this month that private credit is not, in fact, a shadowy bogeyman but “structured finance built on cash flow, enterprise value, and downside protection.” Far from venture-style risk-taking, they argue that many private debt vehicles are publicly listed or institutionally backed, while reporting audited financials and operating under legal and fiduciary obligations. To be sure, they add, there are riskier parts of the market with looser standards such as covenant-lite loans, aggressive structures, or promises of liquidity where underlying assets are illiquid.

Earlier this month, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management CIO Lisa Shalett told Fortune she was particularly concerned about how much of the spending boom has been driven by private credit. “Every morning the opening screen on my Bloomberg is what’s going on with CDS spreads on Oracle debt,” she said, referring to credit default swaps, the financial instrument infamous for the role it played in the 2008 Great Financial Crisis global market meltdown. “If people start getting worried about Oracle’s ability to pay,” Shalett said, “that’s gonna be an early indication to us that people are getting nervous.”

The long view: opportunity vs. oversight

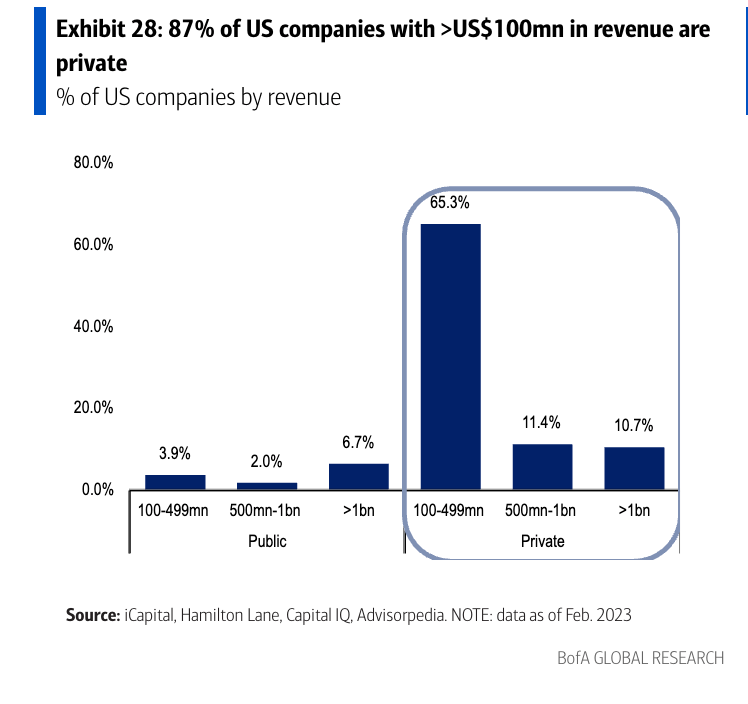

The tectonic shift toward private investing carries enormous implications for society. BofA analysts note that as private firms scale, they shape how technology develops, how jobs are created, and how risks are managed. The top 120 private unicorns now boast a total valuation roughly equal to Germany’s entire market cap, signaling their outsized influence on the global stage.

Jim Rossman, the global head of Barclays’ shareholder advisory group, has been tracking private assets with a particular focus on hedge funds for decades on Wall Street, and he sees a wider transformation taking place. “The growth of private capital is really a reflection of the fact that companies, particularly these now that Apollo and Blackstone and TPG, are closing in on trillion-dollar platforms,” he told Fortune in a recent interview, noting that they’ve acquired their own insurance companies in some cases and are growing beyond the traditional conception of an investment firm.

These firms are so flush with capital and assets, Rossman said, that he sees the private capital boom facilitating the growth of alternative platforms to public markets. “You could see an age when private equity, private capital allows companies to remain in a private format for longer. And if 401(k)s get opened up” for private equity investments, he added, he could envision some kind of investment platform where wealth advisors could invest money just as freely in the private capital space as they can now in equities. “And that would give you exposure to a much broader part of the economy than just what’s public.”

More generally, Rossman added, the world of finance is undergoing many changes. “I think there’s a technology change, a generational change, and then finally, the structural change [that] may be the most important is the growth of mutual fund investing.” Instead of seeing private capital as a shadowy and risky thing, Rossman argued it is opening up more kinds of companies to investment, and that will likely grow, even mutate in surprising ways to many investors.

Rossman recalled buying his first mutual fund through a leading asset manager in the late 1990s: “It cost 300 basis points, three percentage points to join, and they would select 28 interesting technology companies … and then, oh, the expense ratio would be two-and-a-half, 250 basis points a year.” Today, he said, the index-fund revolution has democratized access to the point where you can get the same fund for just 5, 15 or 25 basis points. “It’s just so incredible.”

As the line between public and private capital blurs, the $22 trillion world of private capital is not just a financial story—it’s a signpost for how our economies, companies, and innovations will be built and valued in the years to come. With private assets rivaling the size of national economies and the biggest names in tech betting big outside the public eye, top analysts believe this is a revolution that’s just getting started.

First Appeared on

Source link