Is NASA losing the moon race? SpaceX Starship’s megarocket launching Monday may have answers

Calls for the United States to return astronauts to the moon before the end of the decade have been increasingly loud and frequent, emanating from bipartisan lawmakers and science advocates alike. But underlying that drumbeat is a quagmire of epic proportions.

NASA plans to use SpaceX’s Starship — the largest rocket system ever constructed — for a key portion of the lunar journey, yet it’s still unclear whether the vehicle will work. And a fierce competitor is nipping at the agency’s heels.

“The China National Space Administration will almost certainly walk on the moon in the next five years,” Bill Nye, the entertainer of “Science Guy” fame and CEO of the nonprofit exploration advocacy group The Planetary Society, said during a recent demonstration against the Trump Administration’s plans to cut science funding. “This is a turning point. This is a key point in this history of space exploration.”

Starship is still in the nascent stages of a long and laborious development process. So far, parts of the vehicle have failed in dramatic fashion during six of its 10 test flights. Another prototype recently exploded during ground testing. SpaceX is set to launch its next test, Flight 11, as soon as 7:15 p.m. ET Monday from the company’s South Texas launch facilities.

The megarocket has yet to hit several key testing milestones. These include figuring out how to top off Starship’s fuel as it sits parked in orbit around Earth. Such a step is necessary given the vehicle’s design and enormous size — but it’s never been attempted before with any spacecraft.

Adding to the uncertainty is that no one knows exactly how many tankers full of fuel SpaceX will need to launch to give Starship enough gas for a moon-landing mission, which NASA has planned for mid-2027.

One SpaceX executive estimated in 2024 that number “will roughly be 10-ish.”

But, more recently, engineers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston estimated that a single moon landing could require SpaceX to launch more than 40 tankers — which are Starship vehicles designed to carry fuel, according to one former NASA official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

That estimate may be specific to the current version of Starship, referred to as Version 2 or V2, that SpaceX is flying, the source noted. And the company is expected to debut an upgraded version of the vehicle after its next test mission on Monday that could change those predictions.

Still, even if the number of refueling flights is somewhere between 10 and 40, in general, the path NASA has chosen to return to the moon is “extraordinarily complex,” Jim Bridenstine, who was NASA administrator during President Donald Trump’s first term, said at a Senate committee hearing in September.

“This is an architecture that no NASA administrator that I’m aware of would have selected had they had the choice,” Bridenstine said, referring to the decision to use Starship as the vehicle that will land astronauts on the moon. That choice was made in 2021 when the space agency was without a Senate-confirmed leader.

Acting NASA administrator Sean Duffy responded to the Senate hearing during a September 4 town hall with agency employees, saying the hearing amounted to “shade thrown on all of us.”

“Maybe I am competitive. I was angry about it,” Duffy said. “I’ll be damned if that is the story that we write. We are going to beat the Chinese to the moon.”

A spokesperson for current NASA leadership declined to provide comment for this story, citing the government shutdown.

Given Starship’s gargantuan size and refueling needs, NASA’s road map for its planned moon-landing mission, called Artemis III, appears far more convoluted than the Apollo missions of the 20thcentury.

On those lunar treks decades ago, NASA launched a single rocket — the Saturn V — that had everything the astronauts needed already on board, including the Apollo crew capsule and the landers, such as the Eagle, they rode to the moon’s surface.

NASA is not repeating that streamlined approach for several reasons.

For one, spaceflight is not as simple as dragging out blueprints from old missions. The supply chains, construction methods and institutional capabilities that built the Apollo launch vehicles no longer exist.

Even if NASA could resurrect its retro rockets, the space agency has made it clear that path wouldn’t align with its goals.

NASA hopes the Artemis program will accomplish far more difficult missions than Apollo, including allowing humans to visit the moon’s largely unexplored south pole region, where researchers believe water is stored in ice form beneath the dusty surface. It’s trickier to land there due to the rough terrain and a flight path that requires far more energy. But water and other lunar resources could be harvested and used to sustain a moon base where astronauts would live and work.

The goal — as NASA leadership frequently says — is not to merely plant a flag on the moon but to pave the way for a permanent crewed operation.

Such a vision requires far larger and perhaps more versatile lunar landers, according to former NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, who helmed the agency under President Joe Biden.

“For the research that we’re going to do on the surface of the moon, particularly at a very difficult place to get — the south pole — it takes a larger lander,” Nelson told CNN during a September phone call.

“You just simply can’t take everything with you,” like the Apollo astronauts did, he added, “because of the law of physics.”

Still, critics argue, it’s possible for NASA to carry out a moon mission that — while not as simple as Apollo — is at least less complicated than relying on Starship.

Under the current road map for Artemis III, the mission will begin with the launch of a single, bare-bones Starship vehicle that will serve as a refueling depot. That spacecraft will sit in orbit as it waits for additional Starships, also flying with nothing but propellant as cargo, to launch, dock with the depot and pass off more fuel.

Whether it requires 10 launches or 40, the process must be carried out quickly to counter the effects of fuel boiling off, noted Doug Loverro, a consultant who previously was NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration. Loverro resigned from NASA, as CNN previously reported, because he improperly communicated with an Artemis contractor.

The cryogenic fuels Starship requires must be kept at super-cold temperatures or else they will evaporate. And it’s not clear just how much propellant may boil off as it is moved from one place to another in space.

“Nobody knows how efficient the transfer is going to be,” Loverro said. “It’s nearly an impossible question to answer.”

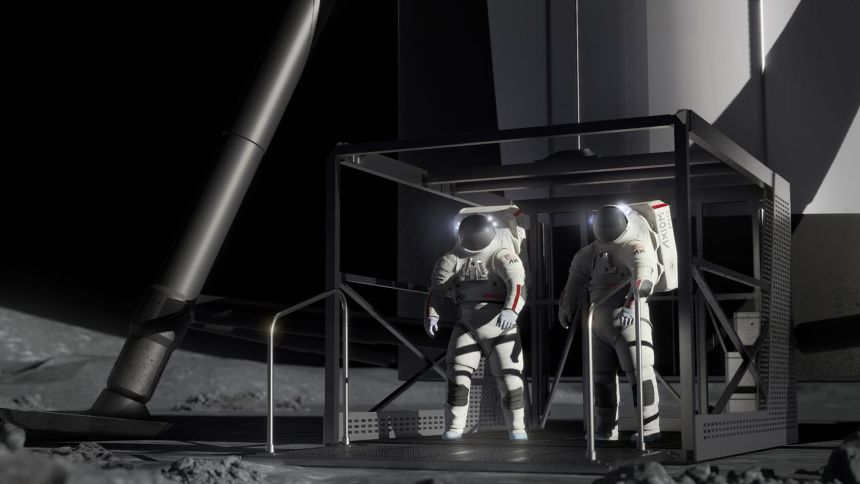

Once the refueling depot is filled up, SpaceX would then launch a Starship vehicle that is equipped to carry humans — called the Starship HLS, or Human Landing System — which would be decked out with all the systems necessary to support life.

Only after the Starship HLS docks with the refueling depot and is topped off with propellant can it begin its trek to the moon.

Meanwhile, NASA astronauts will launch into orbit aboard a different vehicle: the Orion spacecraft, which rides to space atop NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

Following launch, Orion separates from SLS and begins its own journey to orbit around the moon. Once there, the Orion spacecraft will link up with the Starship lander, docking while orbiting above the moon’s surface. Two of the astronauts will then transfer to the Starship HLS, which will carry them down to the moon’s south pole, a treacherous area pockmarked with steep craters.

After about a week, the astronauts would then climb back aboard Starship HLS and launch into lunar orbit where they would once again dock with Orion. The Orion capsule would fly the astronauts back to Earth, making a splashdown landing in the Pacific Ocean.

If NASA achieves its hope of carrying out this mission in mid-2027, it would beat China’s goal of pulling off an astronaut landing by 2030.

NASA’s plan, however, is “incredibly hard, complex” and likely a decade away from reality, Loverro said.

From his vantage point, Loverro said NASA’s decision to use Starship as the lunar lander for the Artemis III mission was made in error.

SpaceX made big promises on paper, he said, referring to the bid the company submitted to secure the $2.9 billion contract for the job. And while Loverro said he believes the company will eventually deliver on its pledges to make Starship operational — he also thinks there is no way it will have the vehicle ready before China lands astronauts on the moon.

SpaceX did not respond to a request for comment for this story, nor does the company typically respond to requests for information.

One former NASA official close to the selection process told CNN that Starship beat out its competitors in a series of technical evaluations that a team of NASA experts conducted. The assessments evaluated Starship’s capabilities as well as costs to the government — an important consideration because NASA had limited funds to dole out.

“It was not like this was a controversial decision at that stage” from the agency’s point of view, the source said, adding that NASA would have liked to have chosen two companies to compete to build lunar landers but simply did not have the money.

SpaceX’s competitor, Blue Origin, sued the federal government over the decision, alleging the space agency unfairly favored SpaceX. But a judge ultimately upheld NASA’s decision. (After Nelson lobbied Congress and secured additional funds, NASA brought Blue Origin on as a second contractor in 2023 to build lunar landers for use later in the Artemis program.)

SpaceX’s Starship promised not just to get the job done for the moon landing — but to be transformative for the space industry. The massive rocket could conduct missions NASA could previously only dream of.

Still, critics say, Starship was likely chosen for its future promise, not for its potential to perform under an ever-looming deadline.

“It — quite frankly — doesn’t make a lot of sense if you’re trying to go first to the moon, this time to beat China,” Bridenstine said during his testimony in September.

However, Duffy, the acting NASA chief, indicated that the space agency remains confident in SpaceX.

“I think it’s important to be honest, and if I thought we were going to have concerns — I would tell you,” Duffy told CBS News in August. “And if there’s a point that I do have concerns, I’ll make that public.”

Despite a growing chorus of voices expressing concern that pinning the outcome of a moon race on Starship may be a losing bet, not many stakeholders are ready to decry the plan publicly or recommend shifting course.

In fact, Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, a key figure in US space policy, made it clear during a September hearing that he thinks it is too late to ditch Starship for an alternative plan: “Any drastic changes in NASA’s architecture at this stage threaten United States leadership in space,” Cruz said then.

Behind closed doors, however, some space industry leaders have voiced deep concerns.

When asked about the public discourse, Loverro said that it’s possible that the gravity of the issue may not have fully sunk in across space industry leadership.

“I think we’re really at step one of the 12-step process of figuring out we have a problem,” he said.

Still, others remain optimistic, pointing to SpaceX’s remarkable success across other projects it has worked on with NASA, such as the International Space Station’s Commercial Crew Program.

During a September 21 meeting of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, member Paul Hill, who had visited SpaceX’s Starship development facilities in August, said the timeline for this vehicle is “significantly challenged.”

The ASAP committee expects the vehicle will be “years late” to the 2027 deadline, Hill said.

In a September 23 statement responding to the meeting, NASA press secretary Bethany Stevens said the agency “appreciates the opportunity to hear from our advisory groups and stakeholders. …These discussions are important to helping NASA safely execute our missions.”

However, Hill also complimented SpaceX, repeating sentiments frequently voiced by space industry leaders and stakeholders: Even if SpaceX is behind schedule, the company has a long track record of excellence and tends to get things done even when conventional wisdom suggests it will fail.

“There is a multifaceted, self-perpetuating genius, for lack of a better way of saying it, at SpaceX,” Hill said, heaping praise on the company’s business model and development approach. “There is no competitor, whether government or industry, that has this full combination of factors.”

First Appeared on

Source link