It May Be Safe to Nuke an Earthbound Asteroid After All, Simulation Suggests : ScienceAlert

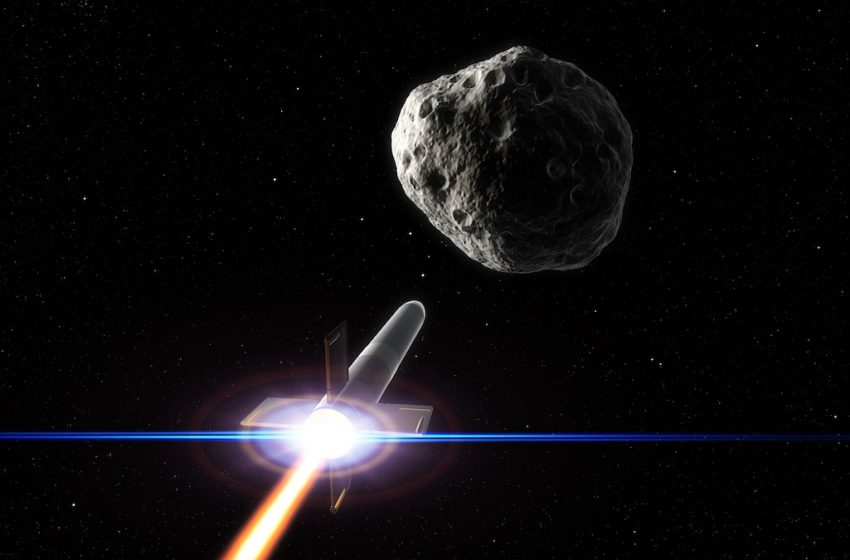

Could humanity nuke an incoming asteroid to deflect it and save the Earth, disaster-movie style? A unique new impact simulation suggests that a nuclear option could be a viable last resort to avert an apocalypse.

Researchers have recently found that space rocks can withstand much more stress than previously inferred from experiments and observations. Counter-intuitively, asteroids actually grow stronger when subjected to an intense impact.

It may sound discouraging, but this discovery can improve planetary defense strategies because it suggests that a nuked asteroid will remain intact, rather than fragmenting into many space rocks that would rain down across our planet.

As detailed in a recently released paper, a team of researchers, including physicists from the University of Oxford, partnered with the Outer Solar System Company (OuSoCo), a nuclear deflection startup, to analyze what happens to an iron space rock under different levels of stress.

“These analyses are intended to examine changes in the meteorite’s internal structure caused by the irradiation and to confirm, at a microscopic level, the increase in material strength by a factor of 2.5 indicated by the experimental results,” explains Melanie Bochmann, co-founder of OuSoCo and co-leader of the research team.

Like the DART mission displayed in 2022, one promising way to avert an asteroid-induced apocalypse is to deflect the incoming threat with a kinetic impactor, a human-made cosmic battering ram sent to smash into a looming asteroid at many times the speed of a bullet.

It’s conceptually simple, but the reality is fraught with perilous uncertainties; a hit in the wrong spot may only delay an asteroid’s doomsday approach toward Earth. Furthermore, the impactor’s energy and the asteroid’s material response can lead to unexpected consequences like fragmentation or a surprising shift in momentum.

So, to decide between an impactor like DART or an as-yet untried nuclear approach, planetary defenders must ascertain the mechanical behavior of different asteroid materials. This knowledge is essential to transfer energy to said asteroid and redirect its trajectory away from Earth.

Yet such data is scarce, especially data that shows how materials react in real-time. For example, different models yield different values for yield strength, a measure of how easily a body breaks under stress.

These models may differ by up to a factor of seven, depending on whether they test for local (microscopic) or bulk (macroscopic). Additionally, the destructive nature of previous tests precluded direct measurement of material responses as they occurred.

“This is the first time we have been able to observe – non-destructively and in real time – how an actual meteorite sample deforms, strengthens and adapts under extreme conditions,” says Gianluca Gregori, a physicist at the University of Oxford and one of the study’s co-authors.

Researchers employed a unique technique to ensure they didn’t destroy the evidence. They used the Super Proton Synchrotron particle accelerator at CERN’s High Radiation to Materials (HiRadMat) facility to irradiate a sample from a Campo del Cielo iron meteorite, blasting it with high-energy, short-duration proton beam pulses at lower and higher intensities.

As a result, temperature sensors and laser Doppler vibrometry (a technique to analyze surface vibrations) revealed that the meteorite sample softened, flexed, then surprisingly re-strengthened. It also displayed a quality called strain-rate dependent damping, which means that the harder it’s hit, the more effectively it dissipates energy.

This study method provides invaluable data that explain why discrepancies in yield strength observed in previous laboratory experiments differ from evidence of meteor fragmentation in Earth’s atmosphere, and that these discrepancies are due to factors such as internal stress redistribution.

It also highlights that these mechanical properties evolve in real time and should not be assumed to be fixed, as may often be the case in existing asteroid deflection models. Further research will involve other types of asteroid compositions.

Here, researchers chose an iron-rich sample for its relative homogeneity, but more heterogeneous space rocks will exhibit different stress-dissipation capabilities based on the spatial distribution of their constituent materials.

The ultimate scope of this research will hopefully remain theoretical:

“The world must be able to execute a nuclear deflection mission with high confidence, yet cannot conduct a real-world test in advance. This places extraordinary demands on material and physics data,” says Karl-Georg Schlesinger, co-founder of OuSoCo and co-leader of the research team.

Related: NASA: Nuclear Explosion Could Save Moon From Asteroid Strike in 2032

However, should a nuclear option ever be necessary, it likely won’t mirror the movies – no drilling necessary. Instead of loading an asteroid with explosives, some physicists propose a standoff nuclear detonation near an asteroid to vaporize part of its bulk and deflect its orbital path.

This research is published in Nature Communications.

First Appeared on

Source link