Kevin Warsh and Weathervane Economics

On Friday I had some, well, less than positive things to say about the nomination of Kevin Warsh to head the Federal Reserve. As I noted, many news reports have characterized Warsh as a monetary hawk, but I argued that he’s more of a political weathervane: He’s for tight money when Democrats are in power, but all for running the printing presses hot when a Republican is in the White House.

Writing in the New York Times, Catherine Rampell says more or less the same thing I did, but more politely.

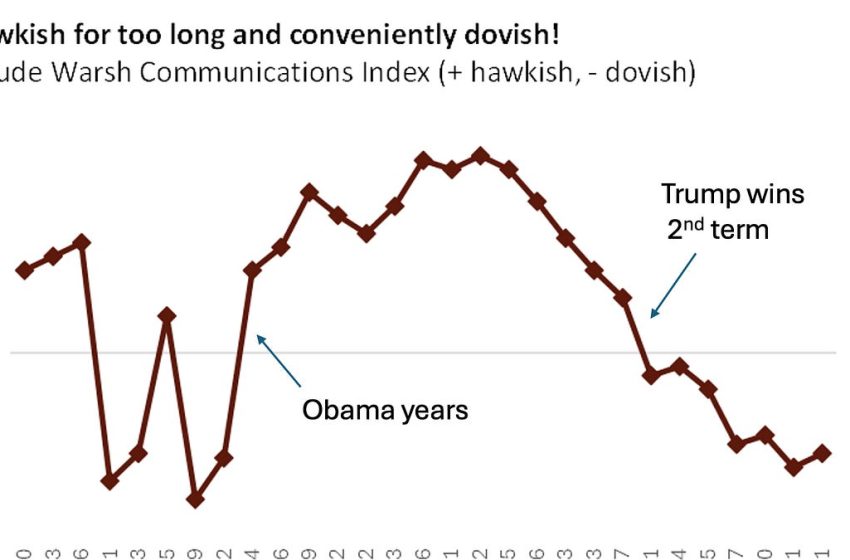

And I have a picture! Neil Dutta of Renaissance Macro, another skeptic, asked Claude to rate Warsh’s speeches and public comments over the years for monetary hawkishness or dovishness. He sent me the chart at the top of this post. Warsh was very hawkish in the years following the 2008 financial crisis. But he turned abruptly dovish … after Donald Trump won in 2024.

If you look carefully at that chart, you’ll see that there’s a gap in the timeline for several years after Warsh was passed over for Fed chair during Trump’s first term. Dutta tells me that this is because he didn’t say enough in public about monetary policy for Claude to rate his position.

Why was Warsh so opposed to easy money after the 2008 financial crisis? Initially he argued against low interest rates and quantitative easing because, he warned, they would lead to excessive inflation. He was, however, completely wrong, and it would have been a disaster if the Fed had followed his advice. As Rampell says,

Of course, plenty of people get predictions wrong. But not usually this wrong, without acknowledgment or explanation of how they’d avoid a similarly catastrophic error next time, particularly when expecting a promotion.

OK, she’s not that much more polite than I was.

It’s also worth noting that Warsh has been extremely caustic, condemnatory and insulting about the Federal Reserve’s track record. But during the biggest, most consequential monetary debate of modern times, Warsh got it totally wrong — while the professional staff at the Fed got it mostly right.

Also, Warsh continued to argue vociferously against easy money even after the inflation he predicted circa 2010 failed to materialize. Rather than changing his views, he came up with new arguments to justify an unchanging policy position, seemingly inventing new economic principles on the fly. I’ll discuss debates about monetary policy at length next weekend, but let me just say here that Warsh’s biggest effort to justify tight money in the face of low inflation and still-weak employment, made in 2015, was an intellectual mess. Larry Summers (I know, I know) called it “the single most confused analysis of monetary policy that I have read this year.”

Given this history, why have so many established economists rushed to say nice things about Warsh? Well, I’m an economist too, and we’re supposed to think about incentives. Imagine yourself as a policy-oriented economist who tries to have contact with and influence over policymakers. Do you want to risk making a bitter enemy out of the next chair of the Federal Reserve? I’m personally wondering how I’ll be greeted at some of the conferences I’m supposed to attend over the next few months.

Still, readers deserve to be told the truth. Warsh might surprise us all by showing unexpected integrity, but don’t count on it. He may be better than the alternatives, but that’s a very low bar, which mainly tells us how sorry a state economic policymaking — actually, policymaking of any kind — has reached in the age of Trump.

MUSICAL CODA

First Appeared on

Source link