Long Covid Is Real — And It’s Changing an Entire Generation

I

n January 2020, just weeks before the NBA shut down and Costco shelves emptied and Tom Hanks got sick, Joy Corbitt’s only brother died in his mid-forties with symptoms of Covid. Which meant, from the pandemic’s earliest days, Joy was taking no chances.

She’d heard that Black and brown people like her seemed to be getting sick and dying at higher rates than other Americans. And that kids were either not getting sick, or getting less sick, or getting sick in ways we didn’t really understand. So, when it came to protecting her then-14-year-old daughter Lia, the North Carolina mother was vigilant.

“I was consumed with the news — consumed with the numbers,” Joy says.

As one week of lockdown slogged into the next, Lia, a straight-A student, struggled through that chaotic, ever unmuted, camera-off Zoom version of school. Which is to say, she didn’t learn much.

With Joy’s husband James, a long-haul trucker, frequently on the road, the mother and daughter did their best to fill the time. They got a crazy Shih Tzu puppy named Zane. They spent long hours playing foosball and air hockey. They watched Netflix and cooking shows and Bridgerton together (yes, even the sex scenes).

By the time fall 2020 poked its head onto the horizon, Lia’s high school was set to resume in-person classes. Joy kept her daughter home. She was anxious; it was too soon for students to return. But Lia, a budding theater kid, was eager to get back to her friends, to her life, to try her luck onstage.

A couple months into the school year, after Lia scored a role in a production of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Joy relented. Lia “just lit up” about theater, her mom recalls. Joy figured, we had to let kids be kids. She took some consolation in the rules mandating universal masking.

The masking, of course, didn’t last long. Kids.

On an otherwise unremarkable day in January 2021, Lia came home with what she described as a “very minor sore throat.” She isolated, per school policy, counting down the 10 days until she could return. On Lia’s first day back, though, her throat was sore all morning. She threw up at lunch. Joy took her home early.

“I was very confused,” Lia says. “I thought, ‘Am I still sick?’”

“I thought it would go away,” she adds, “quickly.”

It didn’t.

Over the next three years, Lia would develop a perplexing, debilitating, and persistent set of symptoms. Extreme fatigue that turned mornings into catatonic nightmares. Brain fog that made memories slippery. Incessant vomiting. It all kept her out of class, stuck in the nurse’s office — or out of school entirely. The straight-A’s evaporated.

Lia’s story is one I’ve heard from dozens of families over two years investigating the impact of long Covid on kids. It’s a slow-moving spiral: first their health, then their grades, then their future. And as the country throttles past the pandemic’s fifth anniversary, those for whom Covid looms very present are feeling increasingly forgotten, subject to pervasive skepticism and a kind of cultural fatigue when it comes to their illness.

Lia and Joy Corbitt at their dining room table in Davidson, North Carolina. “When you have a disability people can’t see,” Joy says, “you don’t get as much empathy.”

Eli Cahan

The Make America Healthy Again movement has recently gestured at embracing the long Covid community. In September, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) convened two roundtables with the stated purpose of bringing long Covid “out of the shadows,” including by launching a “public awareness and education campaign.” Kansas Sen. Roger Marshall — a physician with a loved one suffering from long Covid and who co-led the convenings — says those conversations were the first step to “take this invisible illness seriously.”

But since the earliest days of the second Trump administration, the dollars that could help those suffering from the illness have quietly faded away. In March, cuts to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) disappeared the nearly $2 billion invested in the RECOVER (Researching Covid to Enhance Recovery) initiative, hamstringing research that might have yielded diagnostic tests or better treatments. The same week, the administration shuttered the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Long Covid Research and Practice.

In April, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) gutted the NIH’s Vaccine Research Center — the entity whose work laid the foundation for the Moderna Covid shot. In May, health officials installed by Trump overrode career scientists at the Food and Drug Administration to limit approvals of new Covid vaccines. Around the same time, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. disavowed the vaccine for healthy kids and pregnant women. (“We’re now one step closer to realizing President Trump’s promise to make America healthy again,” Kennedy said in a video announcing the policy.)

In the weeks that followed, the secretary also removed every member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) vaccine advisory committee, replacing them with a merry band of loyalists and skeptics. That committee has since walked back recommendations for the Covid shot. And since the committee’s suggestions only move forward with the approval of the CDC director, RFK Jr. fired Susan Monarez, whom he’d appointed to that role 29 days earlier, for her refusal to “commit in advance to approving every [committee] recommendation regardless of the scientific evidence,” as Monarez later testified at a Senate hearing.

Then there was Trump’s so-called Big Beautiful Bill, expected to boot tens of millions of Americans, including potentially one in five kids, off Medicaid. Where health insurance goes, vaccine access follows: Uninsured or partially insured children are less likely to get the shot, studies show. And unvaccinated children are up to 20 times more likely to develop long Covid.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to requests for comment on how the measures taken since March could impact young people with long Covid. But in the leadup to this school year, these developments led experts to warn that Covid cases may start ramping up again. That could have devastating effects in an education system beset by plummeting achievement levels and an epidemic of absenteeism (more than 10 million kids, or nearly one-third of all school-aged children, regularly missed school last year). And for families already affected by long Covid, absence after absence is prompting threats of investigations for truancy that have led to children being removed from school altogether, either by choice or upon the advice of the district.

“Millions of Americans are impacted by long Covid, and they deserve a federal government that will have their back,” Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine said in response to inquiries from Rolling Stone. “The Trump administration is not only failing to achieve those goals, but actively taking us in the wrong direction.”

It all suggests a brewing public health crisis for a generation of Americans — including people like Lia Corbitt, who, since 2022, has been largely in virtual education. That’s left doting parents like Joy disheartened.

A decorative pep talk on the Corbitts’ bookshelf

Eli Cahan

“When you have a disability people can’t see, you don’t get the same level of empathy,” Joy says. “It feels like the world has moved on.”

THE CDC DEFINES LONG COVID as a wide array of chronic symptoms — including fatigue, difficulty concentrating, memory changes, and sleep disturbances — that began after an infection with the virus and last more than three months. The most recent data from HHS estimated that, as of December 2024, around 22 million American adults had the illness at some point. More than nine million were still sick with it by the end of 2023.

Data is harder to come by for children, who since the earliest days of the pandemic were noted to experience a wider-ranging and less predictable set of symptoms than adults. In February 2024, a paper published in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) estimated that up to six million children in the United States had suffered from long Covid at some point. A year later, CDC researchers put the figure at closer to one million, with 300,000 actively suffering from the disease; it also noted the numbers, based on national survey data, may significantly undercount the illness’ true toll.

Whichever figure you use, the numbers are enormous, rivaling conditions like ADHD and autism as one of the most common chronic diseases in American youth today. And for the children and teens I’ve spoken with, long Covid has done serious physical and emotional damage. It’s also hindered their ability to participate in school — something that becomes an all-encompassing source of frustration for children and parents alike.

All of the students interviewed for this story were diagnosed with long Covid. And they all met the Department of Education’s (DOE) eligibility criteria for specialized school accommodations because of their illness. It’s a group that’s ballooned in size: The number of children receiving specialized accommodations increased by 500,000 after the pandemic relative to before.

There’s Alexander, in eighth grade when the pandemic hit, the adventurer extraordinaire from Massachusetts whose Covid-related exhaustion meant tardy after tardy — but who was denied accommodations because his grades were too good.

There’s Eliza, a kindergartner in Washington state whose severe stomach pain constantly kept her out of school, but who was denied accommodations because the principal said that “we have great teachers here.”

There’s ninth-grader William, a Mets fanatic from suburban New York, who was denied accommodations because school officials told him that “Covid is over.”

Those struggles are despite a July 2021 joint statement from HHS and the Department of Justice clarifying that long Covid is a protected condition under the Americans with Disabilities Act. But early actions under the second Trump administration stand to further jeopardize their ability to access special education. An Inauguration Day executive order targeting DEI withdrew federal support through the DOE for learning loss caused by the pandemic, including from long Covid. (The rollbacks specifically targeted special education for Hispanic, Black, and Tribal communities, whose children who faced higher rates of severe illness due to Covid, and who use special education at higher rates.) The Big Beautiful Bill’s Medicaid cuts likewise stand to dry up billions more in special education dollars.

And should the Trump White House fulfill its campaign promises to axe the DOE entirely, billions of federal dollars upon which schools rely to support millions of children who need special education may vanish overnight.

WITHIN THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY, the legitimacy of long Covid has been a wellspring of controversy.

What the wide-ranging long Covid symptoms have in common is that they’re a challenging combination of persistent yet intermittent, incapacitating yet invisible. Too often, especially for young people, that means adults — even doctors — “don’t believe there’s anything wrong with the child,” says Alexandra Yonts, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who is also the director of the post-Covid program at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. “They think they’re being a teenager.”

At various points, skeptical doctors have attributed the symptoms to a kind of neurosis: patient as hypochondriac, equipped with a fancy new diagnosis. “It is hard to know if this kind of long-tail phenomenon is more pronounced or more common [with Covid],” Adam Lauring, an infectious disease doctor at the University of Michigan, told The Washington Post in June of 2020, “or we are just seeing things that come to our attention because there is a heightened awareness.”

Other doctors have chalked up the symptoms to a kind of societal malaise: patient as emotional sponge in a chaotic world, sickness quite literally all in their heads. “Whether long Covid can be considered just a consequence of a viral infection or should be attributed to the implications of ‘the pandemic era’ we are now living in is still a matter of debate,” Achille Marino and Rolando Cimaz, pediatric rheumatologists at the University of Milan, wrote in 2022 in the journal of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Some in the medical community have even called for dumping the diagnosis altogether. “It is time to stop using terms like ‘Long Covid,’” John Gerrard, former chief health officer of Queensland, Australia, wrote in a press release for a March 2024 study comparing symptoms of Covid patients to those with the flu. “This terminology can cause unnecessary fear, and in some cases, hypervigilance to longer symptoms that can impede recovery.”

Another piece of the long Covid puzzle is a practical issue: getting diagnosed.

According to Elizabeth Pray, former president of Washington state’s chapter of the National Association of School Nurses, who herself has cared for numerous kids with symptoms of long Covid, there are two major steps in the diagnostic odyssey. First, the child needs a documented Covid infection. Second, they need to find a doctor able — and willing — to make the diagnosis.

But many kids may not have tested at the time of their infection, Pray says. Months into the pandemic, the U.S. faced severe shortages in Covid tests for everyone. Well into the winter of 2022, major retailers like CVS and Walgreens were still rationing tests to favor adults, who were at greater risk of severe illness and death. At various points, tests were restricted for kids under 16 years of age, and then under 12.

Even in kids who did test, studies show that up to 90 percent of cases can go missed due to differences in how kids’ immune systems handle the virus. “If you have families that didn’t test,” Pray says, “how would you tie it back to know how big the problem is?”

In the situation where a child does have a confirmed case, finding a doctor to ink the long Covid diagnosis can still be a challenge. According to the patient advocacy group Long Covid Alliance, there are fewer than a dozen long-Covid pediatric clinics across the country, compared with 400 adult clinics. That means many kids who live far from major medical centers — like Pray’s students in Moses Lake, a town of 25,000 that’s 200 miles from Seattle — won’t ever be seen at such a clinic.

Dakota Presnell was one of those kids.

Before the blackouts, the vertigo, the sniffle and the cough, Dakota’s childhood in the seaside North Carolina vacation town of Manteo was idyllic.

Dakota Presnell on a dock in Manteo, North Carolina. He used to spend the summers roller skating and playing in the ocean, his mom says, before his long-Covid symptoms hit.

Eli Cahan

He’d spend summers leaping off story-high footbridges and docks and jetties, and slipping down slides into the rollicking Atlantic surrounding Roanoke Island. In the off-season, he’d roller skate down deserted streets and frequent the laser tag arena or the bowling alley, playing one or the other until they closed up shop.

Dakota was “a happy-go-lucky kid,” his mother, Michelle Hooker, says. “It was hard to keep him home… He was always on the go, always doing something.”

Then, sixth grade. Winter, 2021. Omicron.

Dakota had gone back to school in-person and — like many who contracted Covid’s most infectious variant — he was quickly bedridden, Michelle says. Of all his symptoms, the dizziness and fatigue were the worst. At one point, a friend told Michelle that she should “look into” long Covid; she’d bring it up time and time again with Dakota’s pediatrician, to little avail.

In the summer of 2022, the blackouts started. Out of nowhere, like a limp marionette, Dakota would drop to the ground. Michelle “became his legs,” she says, as she’d carry her son from room to room. By the fall his fatigue and fainting spells were a “complete and utter nightmare.” By January 2024, Dakota’s symptoms also included memory loss and severe pain in his arms and legs that he couldn’t shake.

Michelle says that, during this time, they went to loads of doctors — pediatricians, neurologists, the works — and racked up several hospitalizations where they were seen by still more clinical teams. They accrued loads of diagnoses: non-epileptic seizures, amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome, functional neurologic disorder.

That last diagnosis, in particular, irked Michelle. “That’s a fancy way of saying it’s all in your head,” she says.

Long Covid, she adds, never made the list.

To Yonts, at Children’s National, experiences like Dakota’s are no longer surprising. She’s heard story after story of undiagnosed patients who, by the time they make it to her clinic, have been seen by doctors who “think there’s something else going on, [something] not physical.”

At the same time, Yonts knows specialized long Covid clinics, including hers, can’t see the vast majority of patients who request a visit: Their capacity is “woefully inadequate,” she says. “We’ve had really lengthy waitlists for most of our existence.”

FOR KIDS LIKE DAKOTA suffering from long Covid, navigating school is a mess, too.

Under federal law, any student with a “physical or mental impairment” impacting their ability to participate in school is entitled to accommodations under a so-called 504 or an Individualized Education (IEP) plan. The DOE’s language is deliberately inclusive: Such entitlements stand whether students are diagnosed with — or are “regarded to have” — any such impairment, William Koski, director of the Youth and Education Law Project at Stanford University, says.

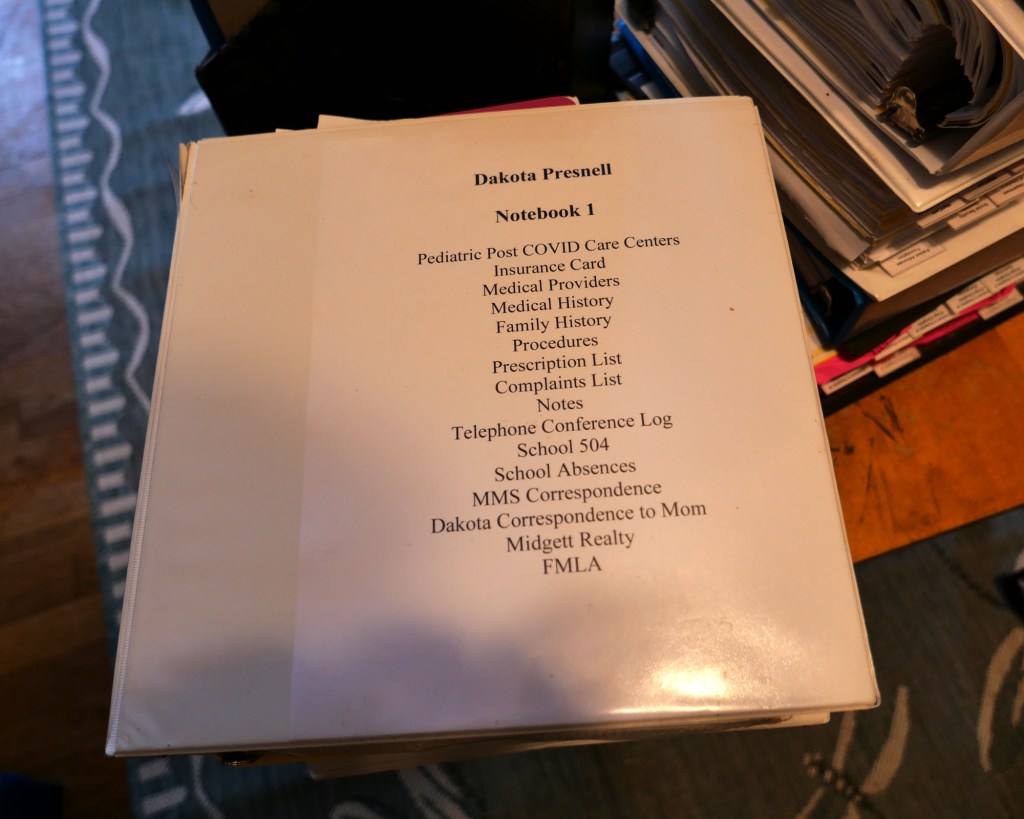

A table of contents for one of many notebooks maintained by Dakota’s mom, Michelle, charting his medical care and correspondence with the school district.

Eli Cahan

The accommodations provided under the plans can run a broad spectrum. They include everything from rest breaks to extra time to provision of quiet spaces for testing. They can also be more tailored: For example, for children with conditions that put them at risk of passing out — in which staying hydrated is critical — accommodations can include things like keeping pretzels or a water bottle at their desk. More intensive plans can include tutors or “changes to the curricular expectations” altogether.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the number of school-aged students with IEPs has jumped. In the 2018-2019 school year, 6.3 million children received special education services. In 2022-2023, 6.8 million did. Still, some long-Covid families say they’ve been in the dark when it comes to accommodations. In some cases, they’ve faced pushback for seeking special education.

That’s true for people like Lia, who had a pre-existing special education plan for ADHD, and who had, by then, a long Covid diagnosis. But Lia struggled to convince her school to provide additional accommodations for her fatigue, nausea, and frequent absences. After much back and forth, the school offered a compromise: She could have two extra days to hand in her homework. Oh, and she could go to the bathroom when she needed to.

“That was really the only change that they gave us,” Lia says.

“If there had been other options,” Joy adds, “they weren’t discussed or offered.”

The obstacles to accommodations have been especially stark for people like Michelle and Dakota, who hadn’t previously navigated special education, and who lacked a formal diagnosis of long Covid. It took more than three years before Michelle realized they could even seek help. “[The school] didn’t give us any information,” Dakota says.

When they finally did hear through Facebook about the possibility of a 504 — and started pinging the school to advocate — things quickly became contentious.

“I’m battling the school,” Michelle says, “[because] they don’t believe anything is wrong with Dakota.”

(Dare County Schools, Dakota’s district, did not respond to requests for comment.)

To Laura Malone, pediatrician and director of the Post-Covid-19 Rehabilitation Clinic at Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, part of the trouble around accommodations traces back to lack of knowledge around the illness. “Long Covid is a newer diagnosis…[that] schools, education systems aren’t as aware of,” Malone says.

Michelle puts it more bluntly. “They don’t believe he has long Covid,” she says of the school. “They don’t believe long Covid exists.”

AFTER MONTHS OF BATTLING, by the beginning of eighth grade in fall 2023, Dakota successfully got a 504 plan. Theoretically, that entitled him to extra time on tests and deadlines, as well as breaks throughout the school day. On paper, it was a version of school that retained a sense of normalcy while being feasible given his fatigue and brain fog.

Unfortunately, the text on paper didn’t translate to real life, Michelle says. The plan “didn’t do much — he was still expected to [take] all these classes, carry all of this homework, do the daily assignments,” she says. “It was kind of a B.S., fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants type answer.”

In this way, Dakota and Michelle’s experience reflects a different issue with learning accommodations: the difficulty implementing and enforcing them.

One of the biggest pieces of the implementation issue is that of dogma, Kathy Riley, nurse at the Plymouth school district in Massachusetts and co-lead for the National Association of School Nurses’ long Covid efforts, says. There are cases where teachers, much like some school officials, simply disagree with the notion that long Covid is real, or that kids with it need help. “The teachers have to buy into the accommodations…or it’s not going to work,” Riley says. “If a teacher doesn’t really agree with it, then the kid doesn’t get it.”

That gets into the problem of enforcement, which typically falls upon the districts themselves. The DOE’s Office of Civil Rights “generally will not evaluate the content” of 504s or IEPs, the agency states on its website. Nor does it “review the result of individual placement or other educational decisions.” Instead, “any disagreement can be resolved through a due process hearing.”

But a 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office found that the ability and willingness of families to pursue such hearings varies widely due to language barriers, ability to find an attorney, legal costs, and fears of retaliation, among other factors. Such barriers were particularly marked in low-income school districts, which on average have more children of color, and which tend to have higher numbers of children with disabilities.

“Many parents feel they are at a disadvantage in a conflict with the school district due to an imbalance of power and so may be reluctant to engage in dispute resolution,” the report concluded. (The DOE did not comment on inquiries from Rolling Stone about the inability of students with long Covid to receive 504s or IEPs, or lack of enforcement of 504s or IEPs in cases where they are granted. )

Recent reporting suggests that kids’ access to special education may worsen further following widespread cuts to the DOE. In March, the administration hollowed out the department’s Office of Civil Rights — including entire investigative teams in the majority of regions — leaving thousands of pending cases in limbo, according to the New York Times. And in May, ProPublica found that, in the period following the cuts, hundreds fewer ongoing cases were investigated, and new cases were dismissed outright at rates 30 percent higher than previously.

In late September, Maryland Sen. Angela Alsobrooks introduced a bill to exempt funding for special education from any future DOE cuts. “Any attempt to slash programs and protections for our students with disabilities is beyond callous,” Alsobrooks said in a press release. Still, by October — amid the government shutdown — mass layoffs were imperiling the DOE’s ability to administer special education, department sources told ABC News.

To Dakota, politics shouldn’t play a role in whether kids with long Covid get the support they need. That’s true for teachers not following certain special education plans rather than others. It’s also true for government-wide initiatives that pull out the rug from under children like him.

“People are inclined to their opinion,” Dakota says, “but at the same time, in some situations, like [with] long Covid…opinions get in the way.”

THE TUG-OF-WAR AROUND accommodations comes at a time when fewer American students are attending school than ever before.

In January 2024, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that chronic absenteeism — defined as the number of students missing at least one out of every 10 school days — nearly doubled following the Covid pandemic. Every state saw increases in chronic absenteeism, the study found: In total, nearly 30 percent — some 13 million children — regularly missed school.

The alarm bells around the absenteeism crisis partly relate to learning loss. In January 2025, an annual Congressional analysis known as the “nation’s report card” found that American students’ achievement levels were declining to some of the worst in recent history.

The alarm is also related to money. Attendance is one of the key factors that determines school funding in most states. That incentivizes schools to do what they can to make sure students show up, since absences can only hurt their bottom line. As a result, some districts are taking a punitive approach to chronic absenteeism. On one extreme is Missouri, where, following an August 2023 decision from the state’s Supreme Court, parents of children with poor attendance records are now liable for jail time.

A more common mechanism involves truancy.

States like Indiana are already moving to toughen truancy laws by introducing bills to tighten attendance requirements and immediately refer families for investigation in ways that can lead to prosecution of children, parents, or both.

Truancy hinges on defining an absence as unexcused. But that’s a definition “really dependent on the school itself,” Christy McGill, deputy superintendent for educator effectiveness and family engagement for the Nevada Department of Education, says.

For example, some schools may require doctors’ notes for every missed day, McGill says, while others do not. Studies have found that children of color were up to four times more likely to have their absences marked unexcused than those who were white.

Rolling Stone contacted every state’s education department for this article, the majority of which did not respond to requests for comment. Most of those that did — Colorado, Kentucky, Oregon, and Utah among them — lack visibility into the reasons for excused versus unexcused absences.

Such variability worries Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national nonprofit organization focused on chronic absenteeism. “Unfortunately, across the United States, absences are too often deemed ‘unexcused’ for arbitrary reasons,” she says.

The lack of clarity around excused versus unexcused absences includes those potentially related to medical conditions such as long Covid. Even as large-scale reviews of children with long Covid find absenteeism to be a consistent issue, schools have little insight into whether poor attendance in their district may derive, in part, from kids struggling with the condition. “There’s no question there could be long Covid symptoms out there we don’t know about,” Eric Mackey, Alabama’s state superintendent of education, says, “[but] I don’t have any information on that.”

(The DOE did not respond to inquiries from Rolling Stone about policies for determining unexcused absences or the initiation of truancy investigations. The agency also did not respond to inquiries about how schools should incorporate protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act into their policies around absences or truancy.)

Many of the families I spoke to, at one point or another, found themselves staring down threats of truancy. For some, those threats came via robocall after robocall. For Dakota and Michelle, they came in meetings with school officials. And for Lia and Joy, they came more insidiously.

“I always wondered what my teachers thought,” Lia says. “They knew I was sick — but did they believe me, [or] did they think I was making it up?”

So, when Lia’s medical waiver fell off seemingly overnight in the fall of 2022, Joy was concerned. If Lia missed 10 days of a given course, she’d automatically fail — if not worse, when it came to the specter of truancy.

(Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Lia’s district, did not respond to requests for comment.)

“I tried to communicate from the beginning that…there is no way, at this point, she is not going to miss more,” Joy says. “[But] it didn’t matter. It felt like she was being punished for being ill.”

AFTER MONTHS OF FRUITLESS morning wake-ups and early afternoon pickups, tardies and absences and missed assignments, months of blackouts and vomiting and forgetfulness and dozing off, Dakota and Lia were left with only one option: hybrid education.

Education outside the schoolyard has long been considered the option of last resort, Koski, at Stanford, says: Keeping kids with their peers “is one of the bedrock principles of …the disability rights movement.”

Based on how their accommodations were implemented, though, the families I interviewed say they felt trapped.

In Lia’s case, even as her 504 entitled her to two extra days to submit homework, she kept racking up absences for not bringing it to class on the original due date. And even as she and Joy heard through the grapevine that other students across the country struggling with long Covid were offered additional services, such IEPs that included hybrid school with teachers coming to their homes for in-person tutoring, she was never offered such a plan.

“Given how the school was handling [accommodations], and their procedures, and their rules, I really had no choice but to switch to virtual school,” Lia says.

That switch came with its own costs. She was always missing out: parties, prom, homecomings. She kept finding herself on the outside of inside jokes. She lost close friends, who accused her of being flaky, or avoiding them entirely. “It’s still affecting me to this day,” Lia says.

Dakota found himself in a similar spot when, this past summer — after Michelle finally had an opportunity to advocate for his special education plan — officials rendered a decision: Dakota would be enrolled at Dare Learning Academy, the district’s “alternative” educational option. It was the worst of both worlds: simultaneously denying Dakota additional accommodations and punting him further to the margins. It also felt like confirmation of what his family had dreaded: that school officials saw him as undisciplined or unmotivated rather than sick.

To Michelle and Dakota, the decision felt premeditated: People “sometimes have their minds made up before we even see them,” Dakota says.

It’s hard to know whether the experiences of kids like Lia and Dakota are becoming more common. The most recent data available from the DOE shows that the number of students in homebound or hospital-bound, residential facility, or separate school-based programs has stayed roughly stable since the pandemic. But that data doesn’t account for the kind of hybrid education that became mainstream during the pandemic. (The DOE did not comment on inquiries from Rolling Stone about how students in hybrid school settings are counted.)

The longer-term consequences on a generation of struggling children taught without adequate support — or via hybrid education — are also not yet clear, says Susan Kressly, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics. But, based on what she’s seen, she’s afraid that “every community is going to pay the price in the long run.”

“We absolutely know the best place for a kid is in school,” Kressly says. In virtual education, she adds, “are we just putting them out of sight?”

Some parents — like Michelle — are already observing changes in their children.

“We’ve been beat up and chewed up, no one’s taken account for what they’ve done, and it’s not fair, because he’s falling through the cracks,” she says of Dakota. “As long as this goes on,” she adds, “his light is getting dimmer and dimmer — because he’s losing hope.”

Dakota, for his part, still has big dreams. He wants to live in a big city (Norfolk, Virginia), and work a demanding job (general surgeon). Dakota thinks he’ll be good, too: “I know how to listen and take other people’s opinions and worries into account,” he says.

But Dakota also knows he faces long odds. And he knows how much his illness plays a role in that. “Long Covid has taken my life and turned it around,” Dakota says.

Lia is also trying to concentrate on the future.

After she got into a pediatric long Covid clinic and began implementing a variety of different treatments — salt tabs day and night, electrolyte powder infused in every drink, this and that medication prescribed off-label — slowly but surely, she has been feeling better. So, she’s got her eyes on the prize. A high school diploma. A college welcome weekend. Most recently, a beauty pageant title.

Even still, life looks different now. In particular, there’s a void where her friends and classmates used to be. “I’m back,” Lia says, “and at the same time, so much has changed, because I’ve missed out on so much.”

This fall, she was excited to make a fresh start at college. New place, new people, new her. A her that feels like the real her. Not the long Covid version.

College “is a place where no one really knows me,” Lia says. “I can start over — and kind of, maybe, separate myself from the illness a little bit.”

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

First Appeared on

Source link