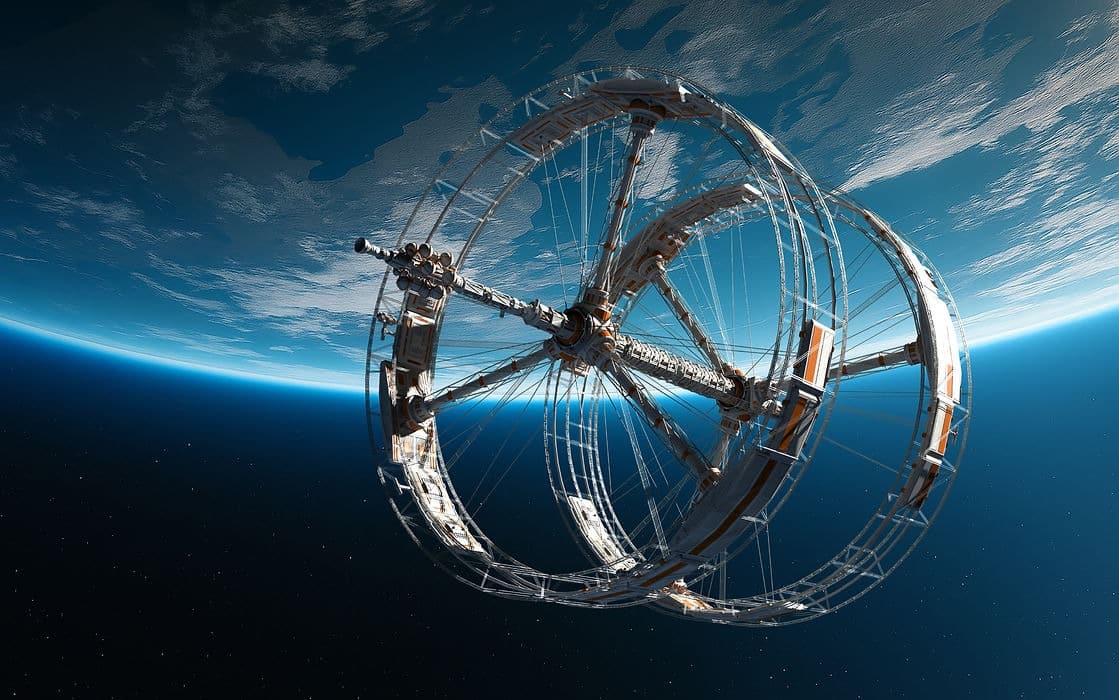

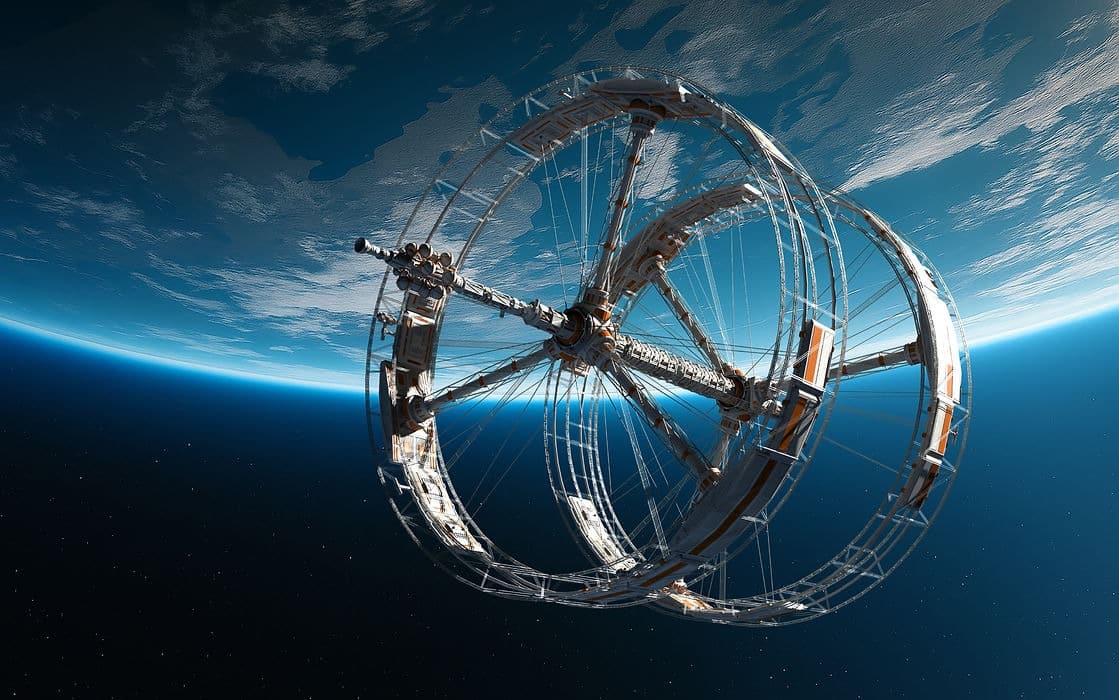

Meet Chrysalis, the 36-Mile Starship Designed to Carry 1,000 Humans Into Deep Space—Forever

When humanity dreams of escaping Earth, the visions often resemble high-tech lifeboats: compact, fast, and bound for familiar planetary destinations like Mars. But one new proposal takes a vastly different approach—by scaling up, slowing down, and removing the return trip entirely.

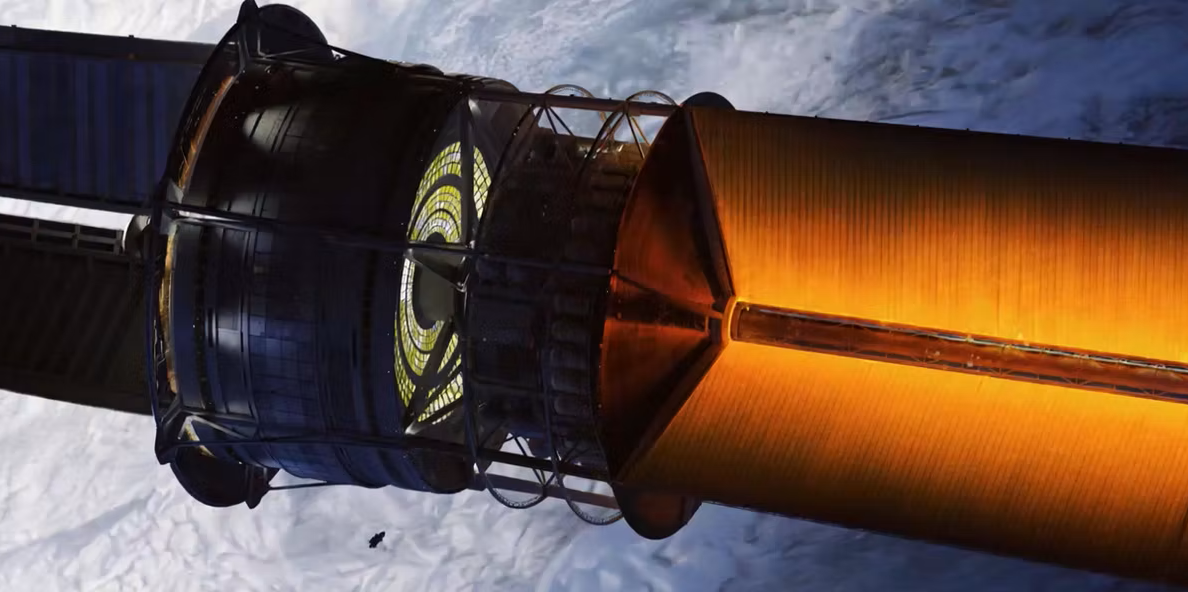

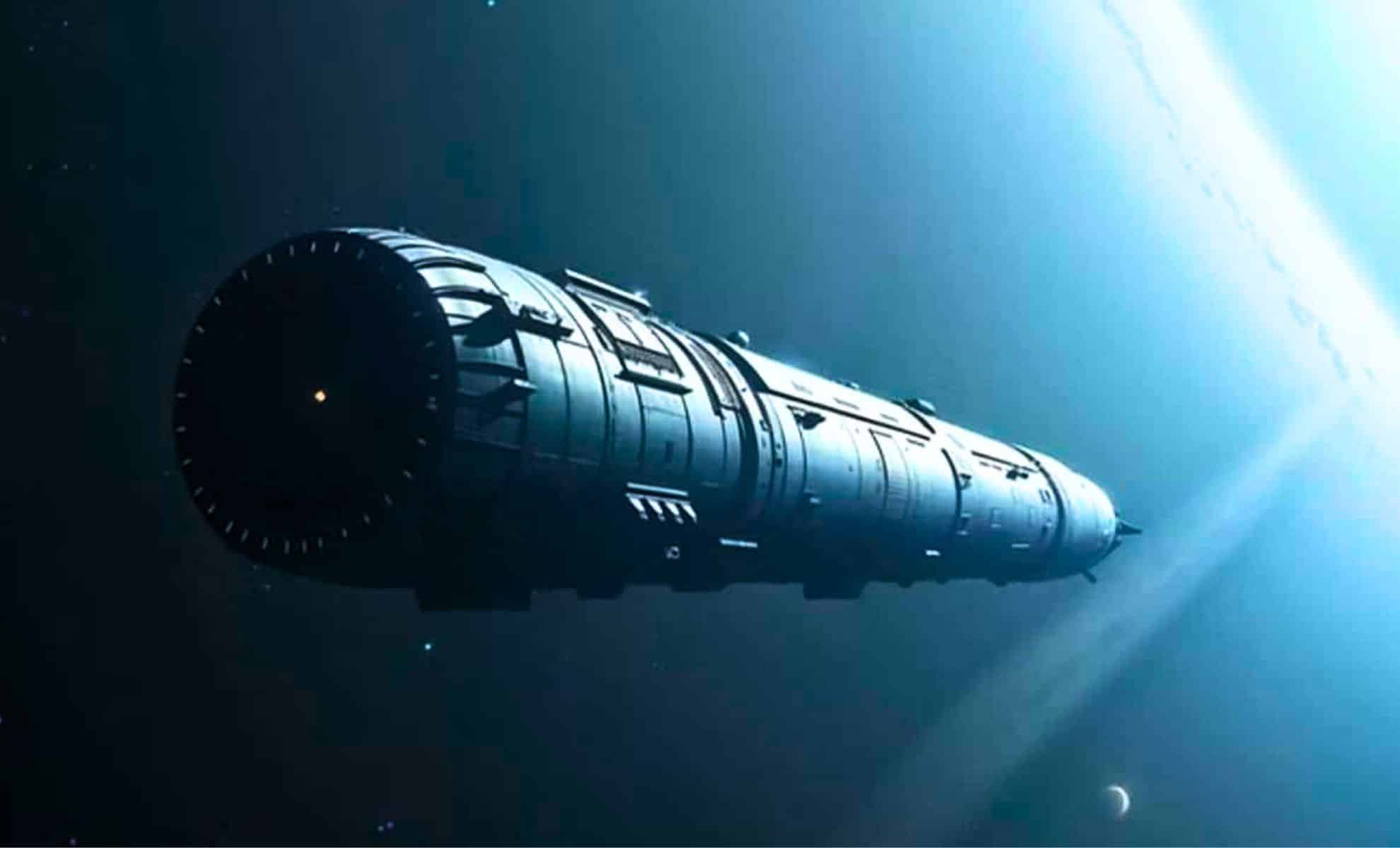

Enter Chrysalis, a theoretical generation ship longer than Manhattan and weighing over 2.4 billion tons. Designed not to ferry astronauts but to host a civilization, Chrysalis would spend 400 years traveling toward Proxima Centauri b, a potentially habitable exoplanet orbiting our closest stellar neighbor, 4.2 light-years away. The crew? Up to 1,000 humans, born and raised aboard the ship—none of whom would ever see Earth again.

The concept, developed for the Project Hyperion design competition, and awarded first prize by the Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is), is as bold as it is haunting: a colossal, rotating spacecraft that doubles as a self-contained world. It would sustain multiple generations of humans through fusion-powered energy, synthetic ecosystems, and artificial gravity. In its ambition and scale, Chrysalis revives a centuries-old dream of generation ships—and brings it closer to engineering plausibility than ever before.

A City Between the Stars

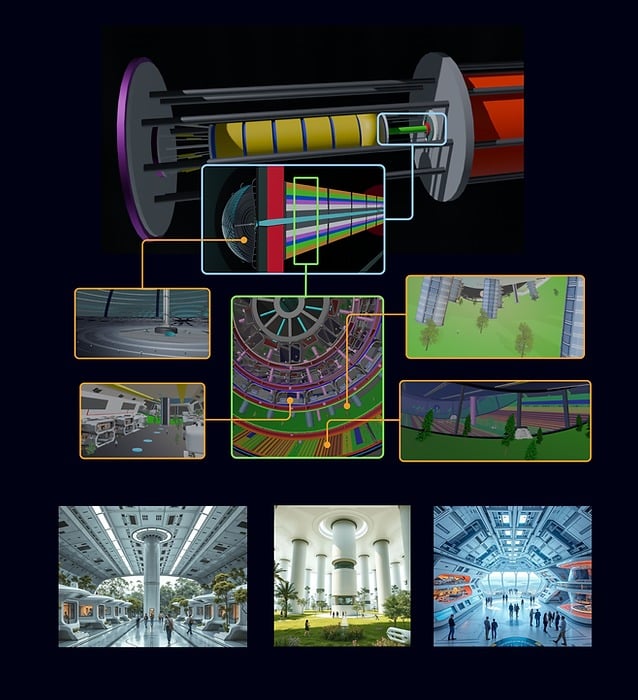

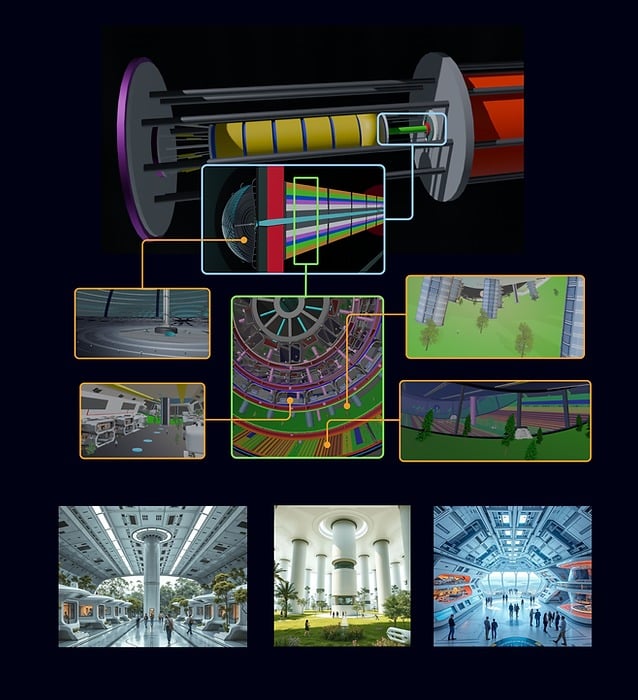

At the heart of Chrysalis lies a radical proposition: stop thinking of starships as transportation, and start thinking of them as mobile societies. Instead of hibernation pods or cryogenic chambers, the ship features concentric rotating cylinders that simulate gravity, vast biome domes mimicking Earth’s ecosystems, and a 130-meter-high cosmos dome designed for annual assemblies and stargazing.

To ensure the long-term health of the crew, Chrysalis integrates centrifugal artificial gravity—a necessity for preventing bone loss, fluid redistribution, and cardiovascular stress associated with microgravity.

As noted by Dr. John Page, senior aerospace lecturer at the University of New South Wales, smaller spacecraft simply can’t rotate fast enough without inducing disorienting side effects, such as blood pooling in the feet or severe motion sickness. In a 2012 interview, Page emphasized that only extremely large spacecraft could rotate slowly enough to simulate gravity effectively without harming occupants.

The sheer scale of Chrysalis addresses this concern. Within its spinning hull, multiple generations would live, age, and adapt to an existence entirely removed from Earth. Food production, waste recycling, and psychological support systems would all be embedded within the architecture. Artificial intelligence systems would assist with decision-making and maintain operational stability, while humans, robots, and software agents would co-manage life support, governance, and education.

In essence, Chrysalis would not just sustain life. It would nurture a culture in motion.

Built Beyond Earth, Tested on the Ice

Constructing such a ship on Earth would be impossible. The design calls for in-space manufacturing, specifically at Lagrange Point 1 (L1)—a stable gravitational zone between Earth and the Moon. According to NASA, L1 offers a low-fuel environment for spacecraft “parking,” and already hosts critical missions like the SOHO Solar Observatory.

In Chrysalis’ case, L1 would serve as both construction yard and launch point, taking advantage of minimal gravitational interference and constant solar exposure for energy and operations. The approach aligns with long-term infrastructure proposals discussed in NASA’s roadmaps and several theoretical mission studies.

Yet perhaps the most human element of the plan begins far closer to home. Before launch, selected crew members would live in Antarctic isolation for decades, simulating the social and psychological conditions of interstellar confinement. The project’s authors argue that adaptation will be “more cultural than biological,” pointing to the need for rituals, governance models, and educational systems that can evolve across centuries.

The idea echoes lessons from long-duration missions on the International Space Station, where even short-term isolation can affect cognition, interpersonal relationships, and morale. In Chrysalis, these stressors would stretch over multiple generations.

From Speculative Fiction to a Strategic Blueprint

Generation ships have long been central to science fiction, appearing in novels by Arthur C. Clarke and Kim Stanley Robinson, or on screen in Interstellar and Passengers. But Project Hyperion‘s competition sought more than fiction—it invited teams of engineers, anthropologists, and architects to explore whether these concepts could work using current or near-future technologies.

Chrysalis was selected from among dozens of submissions, standing out for its system-level integration, modular design, and profound engagement with what it means to sustain a civilization in deep space. Its full technical proposal (PDF) offers not just architectural renderings and power source calculations, but thoughtful consideration of identity, memory, and motivation for future generations born among the stars.

The ship’s vision recalls the worldship concepts proposed in the 1980s, but with updated social frameworks and technical realism. As Hyperion jury members noted, Chrysalis was the only entry to thoroughly explore intergenerational meaning-making, not just survival.

But Chrysalis isn’t just an engineering puzzle. It forces a confrontation with one of the most uncomfortable questions in the space age: not how we get there, but what we become when we do.

First Appeared on

Source link