Metabolism, not cells or genetics, may have begun life on Earth

Planet Earth is overrun with life. Lakes, rivers, seas, and oceans are teeming with it, from the surfaces all the way down to the bottom, often at depths of miles and miles. The land, both above and below ground, is packed with living organisms of varying size, mass, and complexity, including plants, animals, and fungi. Even the atmosphere houses a wide variety of life forms, from birds and insects to microbes found far above the highest mountain peaks. All told, more than 8 million species of organisms are currently represented on Earth, totaling over half a trillion tonnes of carbon in overall biomass.

We can trace our evolutionary history through time, with notable milestones including:

We have fossil evidence of life existing 3.8 billion years ago, but the start of it all — the origin of life itself on Earth — remains an unsolved puzzle. Although many theories and scenarios abound, one of the least-talked-about may actually be the most likely: a metabolism-first scenario for life’s beginnings.

Here’s why recent research, only conducted in the last few years, may revolutionize the story of life’s emergence on our planet.

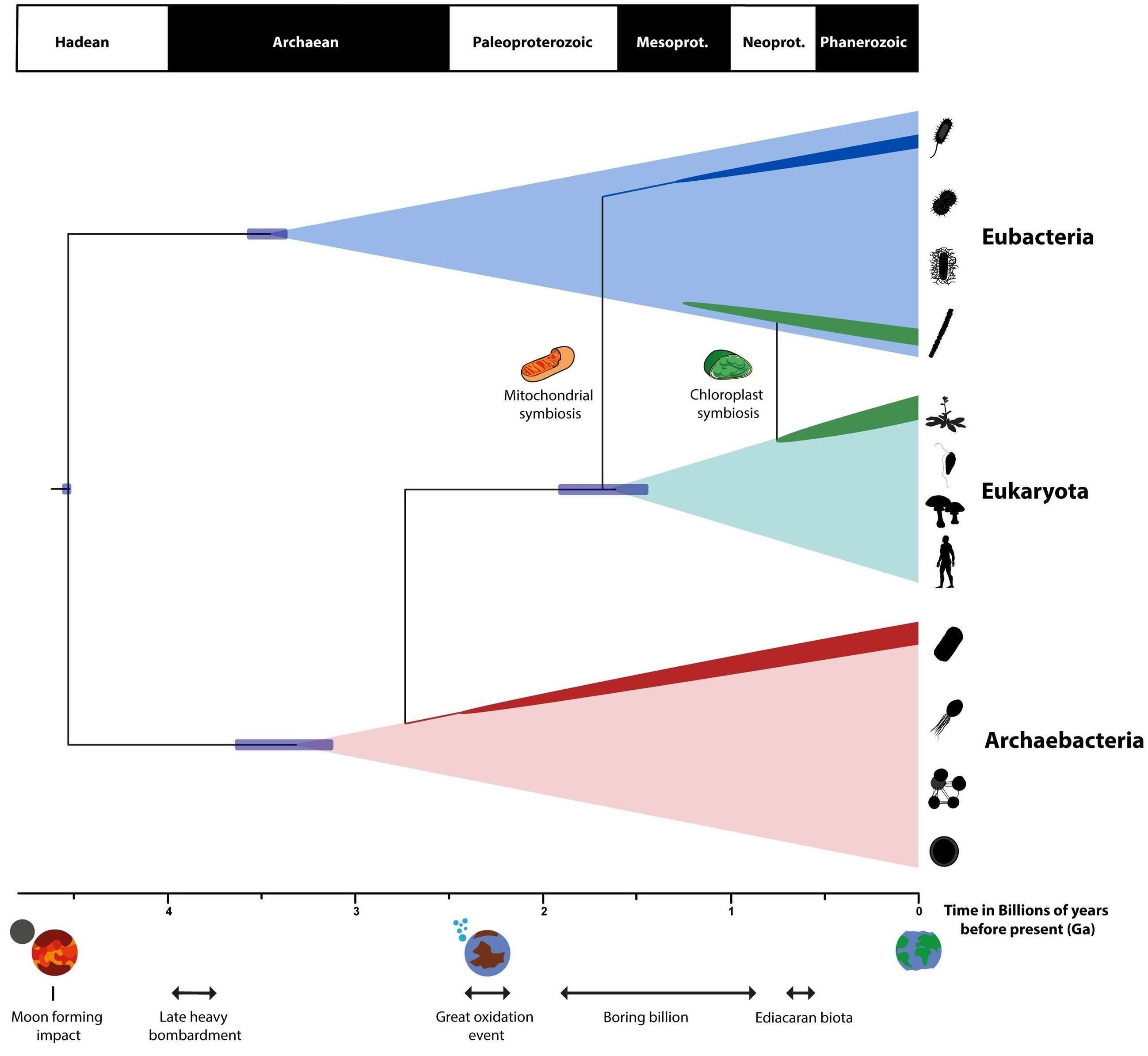

This tree of life illustrates the evolution and development of the various organisms on Earth. Although we all emerged from a common ancestor more than 2 billion years ago, the diverse forms of life emerged from a chaotic process that would not be exactly repeated even if we rewound and re-ran the clock trillions of times. As first realized by Darwin, many hundreds of millions, if not billions, of years were required to explain the diversity of life forms on Earth.

The 8+ billion species of organisms found on our world today possess an enormous diversity of properties. Some are large, some are small; some are complex, some are simple; some live only under specific, extreme conditions, while others thrive in a wide variety of terrestrial environments; some complete their life cycle in only a few hours, while others survive for decades, centuries, or even millennia. There doesn’t seem to be a universal set of conditions — at least, among these and many other common metrics — that you can apply to life.

And yet, there are at least five properties that are universal to all modern life-forms:

- All forms of life collect resources of some type from their environment.

- They all possess a metabolism, where energy is extracted from an external source to achieve the organism’s metabolic goals.

- They all have the capacity to reproduce, making offspring that are partially or even wholly identical to the parent organism.

- They all have a separate “inside” and “outside,” delineated by the existence of a cell wall or cell membrane, creating a boundary between the organism and the external environment.

- And they all have, within them, some sort of genetic code that enables proteins to be synthesized and other life processes to occur.

It’s very unlikely that all of these properties arrived simultaneously, in a fully developed fashion. One of them must have come first.

Early on, shortly after the Earth first formed, life likely arose in the waters of our planet. The evidence we have that all life that’s extant today can be traced back to a universal common ancestor is very strong, but many details concerning the early stages of our planet, for perhaps the first 1-to-1.5 billion years, remain largely obscure. While life arose early on, there is no evidence that Earth came into existence with life already on it, with the origin being uncertain to within 100-700 million years after our planet’s formation.

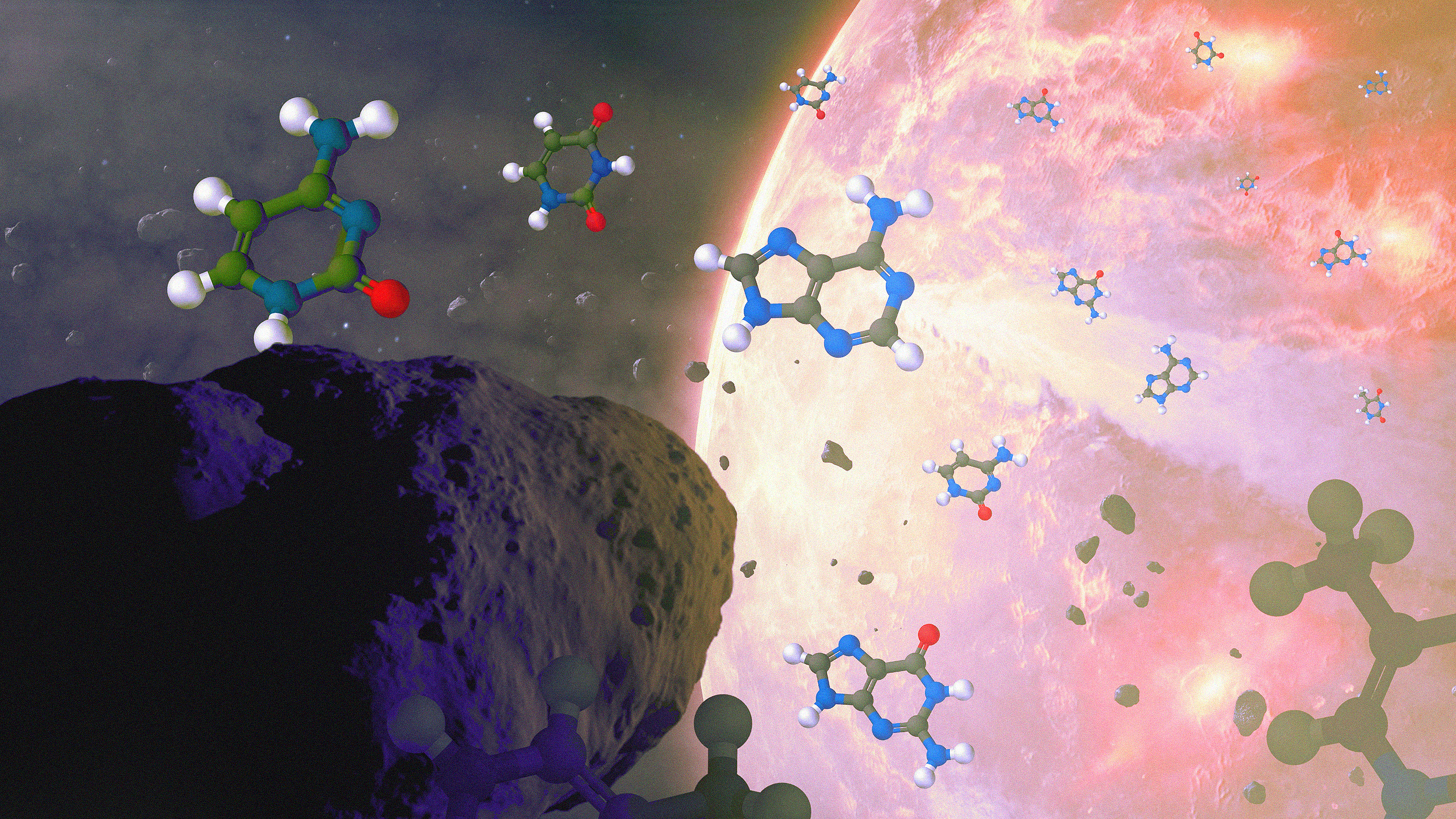

Many look to the raw chemical ingredients at the heart of our understanding of life today, and advocate for their prominence — and even their primacy — in the origin of life. After all, they argue, those raw ingredients, including all of the nucleobases used in terrestrial life, are found extraterrestrially: in asteroids, comets, and other primordial bodies left over from our Solar System’s formation. Even though the odds of a string of those nucleobases randomly forming in a sensible order that encodes a successful protein are astronomically small, they still argue that it only takes one such success to lead to life, no matter how remote the odds.

Others instead point to the necessity of an inside-outside difference. They argue that the first life-forms required a protective layer to withstand the harshness of early Earth’s environment, complete with:

- solar radiation,

- lightning storms,

- heavy bombardment by objects from space,

- and copious volcanic activity,

to avoid proteins denaturing and their sensitive inner constituents from disassembling.

Those who advocate a cellular structure first often rely on the presence of lipids in an aqueous environment to support their argument. But the question of how the information to create such a structure could arise concurrent with all the other necessary functions that life would need to have remains; a “barrier-first” scenario won’t necessarily lead to life processes being carried out.

This conceptual image shows meteoroids delivering all five of the nucleobases found in life processes to ancient Earth. All the nucleobases used in life processes, A, C, G, T, and U, have now been found in meteorites, along with more than 80 species of amino acids as well: far more than the 22 that are known to be used in life processes here on Earth. Similar processes no doubt happened in stellar systems all throughout most galaxies over the course of cosmic history, bringing the raw ingredients for life to all sorts of young worlds.

So how did life originate? Efforts to answer this question took a huge step forward in 2010, when a landmark paper integrated the evidence across the entirety of life on the planet with modern phylogenetics and rigorous probability theory. Previously unchallenged assumptions — such as the notion that similarity in genetic sequences necessarily implies genetic kinship, or that universal common ancestry was a requirement — were thrown out in favor of assumption-neutral tests. Horizontal gene transfer between barely-related species, including species in different kingdoms or phyla, was considered, along with fusion events. No stone was left unturned.

The results of conducting the formal test were as follows:

- Overwhelmingly, the idea that all extant life shares a universal common ancestor is favored, and all alternative hypotheses are disfavored.

- Horizontal gene transfer absolutely does occur, but it is extremely unlikely to occur between organisms descended from separate incidents of cell formation, as their genes would be converted into non-coding segments.

- The fact that the same 22 amino acids — and those 22, out of more than 80 known to naturally occur — are found in biologically produced protein molecules is additional strong chemical evidence in favor of universal common ancestry.

But even with this insight into life’s development and history on Earth, we still couldn’t draw definitive conclusions about its origins.

This image shows the standard RNA codon table, where each of the 64 possible three-base-pair codons involving U, C, A, and G bases are shown. These codons encode amino acids, as well as the information to begin (⇒) or end (Stop) encoding a particular protein out of those amino acids. Note the important feature of redundancy of the table, as there are only typically 20 amino acids for 64 codons. DNA typically encodes 20 amino acids as well, with thymine replacing uracil.

That’s why the newest approach isn’t to choose an assumption about what came first, but rather to begin with the conditions that must have been present on primordial Earth and work backward: what types of reactions would have been likely to occur, or even inevitable?

In the beginning, what would become our Solar System was no more than an enriched cloud of primeval gas. Its composition was about 70% hydrogen, 28% helium, and around 1% oxygen, followed by smaller amounts of other elements, including carbon, neon, nitrogen, iron, silicon, sulfur, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, magnesium, and many others. Some of those atoms were bound up into molecules, including sugars, amino acids, nucleobases, aromatic molecules, and so on. Most of the mass is drawn to the center, where it will eventually form our Sun, but a substantial amount collapses into a rotating disk that surrounds the central protostar: a protoplanetary disk.

While the lightest elements in the inner part of the disk — hydrogen and helium, as well as light species of ice, such as nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide ices — boil and/or sublimate away, the heavier elements coalesce, forming longer-chain, more complex molecules. Over millions of years, imperfections arise in that protoplanetary disk, leading first to protoplanets and later, as the Solar System matures, full-fledged planets.

Although we now believe we understand how the Sun and our Solar System formed, this early view of our past, protoplanetary stage is an illustration only. While many protoplanets existed in the early stages of our system’s formation long ago, today only eight planets survive. Most of them possess moons, and there are also small rocky, metallic, and icy bodies distributed across various belts and clouds in the Solar System as well. Early on, more planets and protoplanets were likely present; the eight that we possess today only represent the long-term survivors.

Early Earth was rife with violent events. The most famous is likely the collision with the protoplanet Theia about 4.5 billion years ago, which led to the formation of our Moon, with a subsequent period of heavy bombardment likely persisting for hundreds of millions of years thereafter. A combination of volcanic events and impacts from comets and asteroids led to the creation of oceans and an atmosphere, and precipitation on the planet’s early, highly uneven terrain led to the formation of freshwater stores, including rivers, lakes, and ices.

Although we colloquially use the phrase “boiling the ocean” to describe an overly ambitious, but practically impossible approach to problem solving, there’s a germ of a sound idea in that phrase that’s relevant. Since oceans are made of mostly water, but with many dissolved or suspended other particles and ions within it, “boiling” provides a method for removing the water while leaving the remaining contents behind. If you were to take even a large scoop of ocean water and began to boil it, you’d lower the fraction of water that’s present, removing it step-by-step, while leaving all of the dissolved and undissolved contents behind.

Now consider the various aqueous environments that our planet possessed early on, and you’ll see why the freshwater stores that formed over volcanically active areas — known as hydrothermal fields — are where Earth’s primordial ingredients were most concentrated. As their water evaporated, the density of organics within them — sugars, amino acids, nucleobases, ions, and much more — increased.

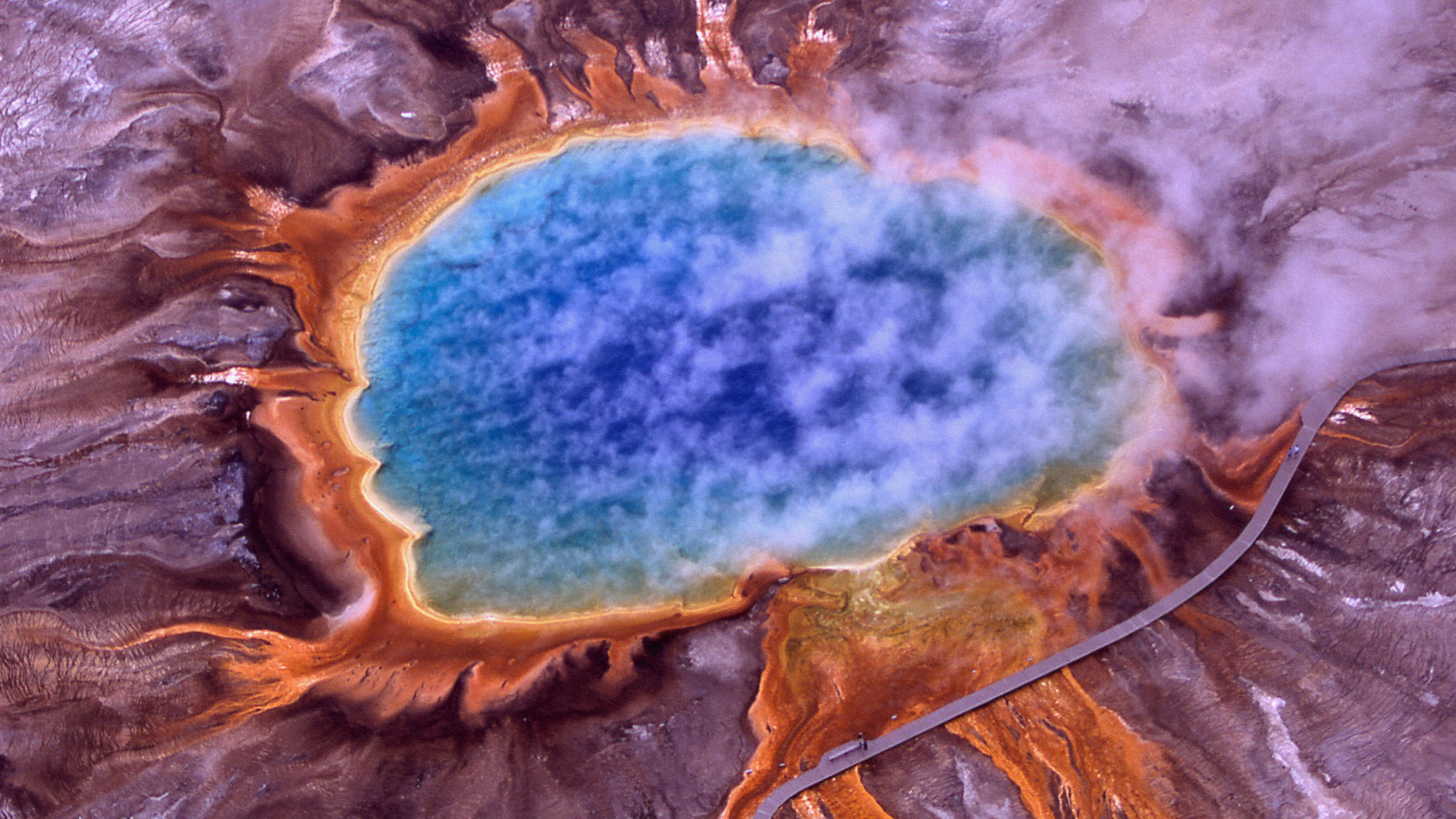

This aerial view of Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park is one of the most iconic hydrothermal features on land in the world. The colors are due to the various organisms living under these extreme conditions, and depend on the amount of sunlight that reaches the various parts of the springs. Hydrothermal fields like this are some of the best candidate locations for life to have first arisen on a young Earth, and may be home to abundant life on a variety of exoplanets.

How can we be certain about the raw ingredients that were present? The best proxy for that is the composition of asteroids, comets, and meteorites. When we look inside these primitive objects — many of which we can date back to ~4.56 billion years ago — we find:

If you create a nutrient and organic-rich environment in the lab, you can do things like make an early-Earth analogue. You can apply energy to it, enable phase changes, and allow long-term chemical synthesis to occur. Large, complex molecules easily emerge, including full-fledged nucleotides, complex proteins, and enzymes. You’ll synthesize not just sugars but polysaccharides and even starches, as well as molecules bearing many similarities to modern cholesterols, alcohols, and lipids.

Then-graduate student Chao He in front of the gas chamber in the Horst planetary lab at Johns Hopkins, which recreates conditions suspected to exist in the hazes of exoplanet atmospheres. By subjecting it to conditions designed to mimic those induced by ultraviolet emissions and plasma discharges, researchers work toward the emergence of organics, and life, from non-life.

Lots of complex, long-chained molecules are going to form in an environment such as this. Amino acids will assemble, link up, and form proteins. Most of those proteins will be completely inactive; they won’t perform any biologically useful functions. However, if you replace the neutral atom at the end of one of those proteins with an ion — particularly with a heavy element ion, such as magnesium — then that protein becomes an enzyme. Suddenly, your previously useless protein gains the ability to do things like:

- cleave molecules in two,

- catalyze energy-releasing chemical reactions,

- and turn previously “useless” molecules into a source of food and/or nutrients.

This isn’t a scientifically validated scenario depicting how life on Earth must have gotten its start, but rather a plausible scenario for how, before there was anything else (a cell membrane, a string of nucleic acids that encoded information, or even the ability to reproduce), there could have been molecules conducting metabolic activity.

As was first shown in a groundbreaking paper in 2013, this idea of a metabolism-first development of life should be considered, if not the default story of how biological life processes developed here on Earth, then at least a default component of the story.

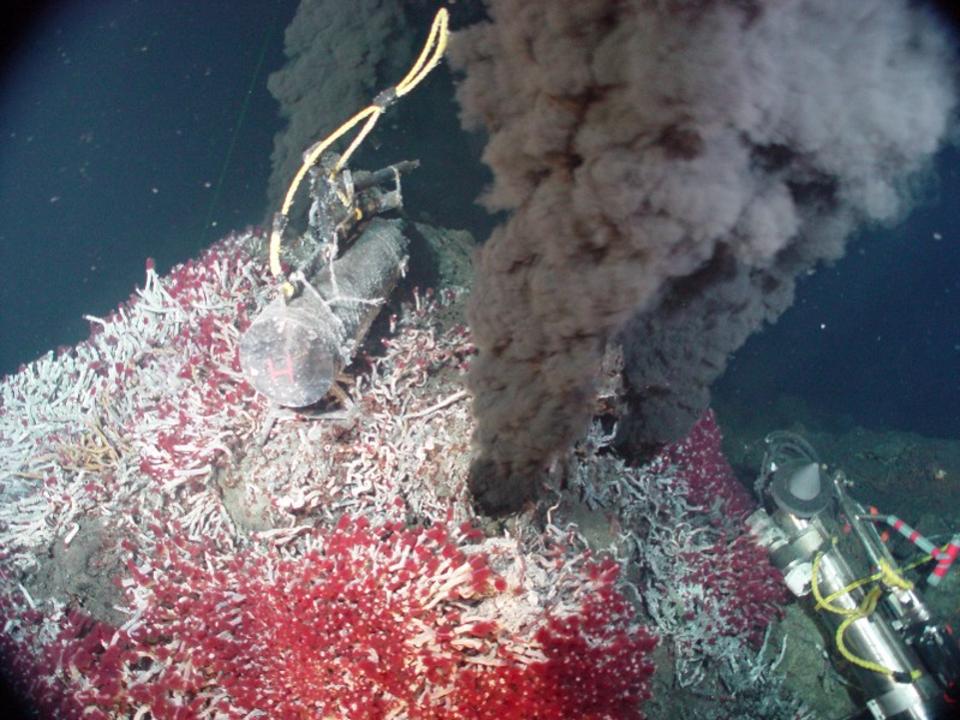

Deep under the sea, around hydrothermal vents, where no sunlight reaches, life still thrives on Earth. How to create life from non-life is one of the great open questions in science today, but hydrothermal vents are one of the leading locations where the first metabolic processes, the precursor to living organisms, may have first arisen. If life can exist down there on Earth, perhaps undersea on Europa or Enceladus, there’s life down there, too.

This conversion from a useless protein to a useful enzyme can occur not only in hydrothermal field situations, but in tidepools, around hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean, at the sea/air interface, or at other locations where non-equilibrium conditions persist. Amino acids interact and smack into one another, spontaneously forming and breaking bonds. Ions come along and bind to these primitive peptides, creating enzymes. Although these molecules are fragile and easy to destroy or denature, they’re very numerous and were found in high concentrations in these early environments, creating copious possibilities — set by the so-large-it’s-barely-fathomable mathematics of combinatorics — that truly boggle the mind.

Some of the proteins that formed likely gained the ability to perform specific functions merely by chance. These functions might have included the ability to:

- hoard resources, including specific peptides that can serve as food,

- split/recombine other molecules in a way that liberates usable energy in the process,

- “bite” or cleave other useful molecules, releasing energy while remaining intact themselves.

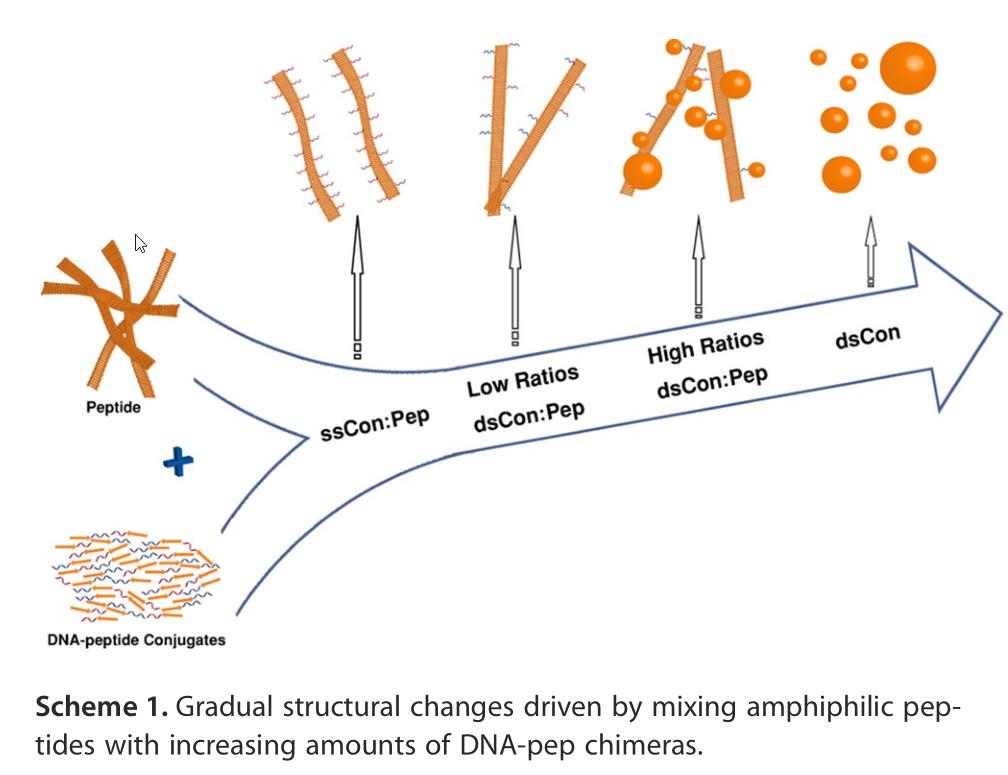

Whatever the case, the 2013 paper showed that the spontaneous creation of these metabolic peptides is all but inevitable. Then, less than 10 years ago, another incredible biological breakthrough was made into origin-of-life research: the discovery of RNA-peptide coevolution.

In an aqueous environment, nucleobases — the genetic “letters” of structures like RNA, DNA, or even PNA (peptide nucleic acids) — may line up along the various amino acids in a peptide chain. If each amino acid can pair up with its corresponding three-nucleobase codon, which can then “peel off” and draw additional amino acids onto that genetic strand, they can effectively reproduce, to a high degree of accuracy, the original peptide chain.

If life began with a random peptide that could metabolize nutrients/energy from its environment, replication could then ensue from peptide-nucleic acid coevolution. Here, DNA-peptide coevolution is illustrated, but it could work with RNA or even PNA as the nucleic acid instead. Asserting that a “divine spark” is needed for life to arise is a classic “God-of-the-gaps” argument, but asserting that we know exactly how life arose from non-life is also a fallacy. These conditions, including rocky planets with these molecules present on their surfaces, likely existed within the first 1-2 billion years of the Big Bang.

The RNA-peptide coevolution scenario, although new on the scene, has rapidly gained a following and is considered by many to be a leading theory for the origin of life not only here on Earth, but possibly anywhere the conditions for life’s emergence exist. The border between chemical and biological processes is blurry, but the idea of a primitive molecule that can metabolize nutrients found ubiquitously in its environment is highly attractive. If you then have an abundance of nucleic acids, and those nucleic acids can spontaneously align along the amino acid sequences that DNA, RNA, or even PNA can encode, you get a mechanism for another key component of life: replication.

If you have a metabolizing replicator that can successfully reproduce before its environment runs out of resources, denatures the molecule, or otherwise drives it to extinction, then the next steps can begin to fall into place, with the development of cell walls or membranes that delineate an “inside” of an organism from an “outside” chief among them.

We still have a long way to go in determining whether life is common, uncommon, rare, or even unique in the Universe; life here on Earth remains the only example we’re aware of. However, the clues to our origins aren’t just written into Earth’s history, but also into the laws and conditions found throughout the Universe. If life happened here, it could happen elsewhere. Perhaps our first detection of life on other worlds will happen in the very near future. Perhaps that discovery, coupled with some key insights into how life first arose on Earth, will allow us to finally understand if metabolism, rather than cellular structure or an underlying genetic code, is the key that unlocks life’s emergence in general.

This article is part of Big Think’s monthly issue Biology’s New Era.

First Appeared on

Source link