New Alzheimer’s Treatment Clears Plaques From Brains of Mice Within Hours : ScienceAlert

Scientists have repaired a natural gateway into the brains of mice, allowing the clumps and tangles associated with Alzheimer’s disease to be swept away.

After just three drug injections, mice with certain genes that mimic Alzheimer’s showed a reversal of several key pathological features.

Within hours of the first injection, the animal brains showed a nearly 45 percent reduction in clumps of amyloid-beta plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

The mice had previously shown signs of cognitive decline, but after all three doses, the animals performed on par with their healthy peers in spatial learning and memory tasks. The benefits lasted at least six months.

Related: Clearing Brain Waste Dramatically Improves Memory in Aging Mice

These preclinical results don’t guarantee success in humans, but they’re an encouraging start, which the authors say “heralds a new era” in drug research.

“The therapeutic implications are profound,” claim the international team of researchers, co-led by scientists at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) and the West China Hospital Sichuan University (WCHSU).

Their approach to treating Alzheimer’s reframes the blood-brain barrier as more than a hurdle to be leapt over, but a gate in need of repair.

The blood-brain barrier separates the blood system of the brain from the rest of the body, keeping dangerous toxins and pathogens away from our seat of consciousness. It also keeps out much of our medicine.

For years now, drug researchers have tried to use nanoscopic packages, called nanoparticles, to smuggle Alzheimer’s drugs across the blood-brain barrier. They’ve also used sound waves (ultrasound) to momentarily open the barrier, to allow drugs to pass.

But these approaches treat the barrier “merely as a gate to cross rather than as a dysfunctional tissue to repair,” write lead authors Junyang Chen and Pan Xiang from Sichuan University and their colleagues.

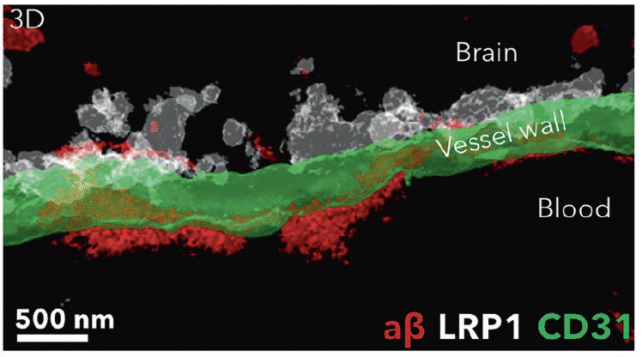

Instead of trying to sneak drugs into the brain, researchers in China and Spain are trying to make it easier for amyloid-beta to get out of the brain.

Their novel approach supports an emerging hypothesis that the blood-brain barrier is weakened or impaired in Alzheimer’s cases, leading to waste products piling up.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, the problem extends beyond access; the very transport machinery itself is pathologically biased,” argues the international team.

Using nanoparticles, not as passive carriers of medicine but as active agents of change, the researchers have altered traffic flow across the blood-brain barrier, restoring clearance of amyloid plaques in mice.

The nanoparticles act as tiny engineers of cellular behavior, the researchers explain, orchestrating repair at the molecular scale. Their ultimate target is ‘endothelial LRP1’, which helps remove amyloid-beta plaques at the blood-brain barrier.

“The long-term effect comes from restoring the brain’s vasculature,” explains bioengineer Giuseppe Battaglia from IBEC.

“We think it works like a cascade: when toxic species such as amyloid-beta accumulate, disease progresses. But once the vasculature is able to function again, it starts clearing amyloid-beta and other harmful molecules, allowing the whole system to recover its balance.

“What’s remarkable is that our nanoparticles act as a drug and seem to activate a feedback mechanism that brings this clearance pathway back to normal levels.”

Today, effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease are proving tricky to find. The latest drugs, which target abnormal clumps and tangles in the brain, have produced mixed results.

While drugs like lecanemab and donanemab can somewhat slow down Alzheimer’s symptoms, they can’t reverse the disease or stop its progression, no matter how scientists try.

Some researchers think we’ve gotten ourselves into a bit of a rut. They argue we’ve been too focused on clearing plaques and tangles inside the brain, when Alzheimer’s may actually start at the brain’s borders.

Julia Dudley, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, who was not involved in the current study, says it’s too early to say if this strategy will work in people. Mice don’t have the same brain vasculature as humans, and the current study only examined a very specific subtype of dementia in a small number of rodents.

Still, Dudley says the results add to growing evidence that “repairing the blood-brain barrier itself could offer a new way to treat Alzheimer’s.”

“This type of research – while still early – is crucial for taking us closer to finding a cure,” she writes.

The study was published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.

First Appeared on

Source link