Paleontologists Found a Clue Hidden in T. rex Bones for 66 Million Years and It Rewrites Everything They Thought They Knew

A new peer-reviewed study suggests the iconic dinosaur reached full size between the ages of 35 and 40, significantly later than previously estimated.

The research, published in PeerJ and led by professor Holly Woodward of Oklahoma State University, is rewriting the narrative around how the T. rex lived and matured. Using advanced bone analysis and statistical models, the team uncovered that these dinosaurs spent far more time in intermediate growth stages, calling into question some longstanding assumptions about their life history.

This shift in understanding has broad implications. It not only challenges the timeline of T. rex development but also its ecological role throughout life. Scientists are now reevaluating the idea of a single, dominant predator rapidly reaching its peak and instead considering a more flexible, dynamic growth journey. It also raises questions about whether all fossils labeled T. rex really belong to the same species. For the scientific community, this changes how researchers might interpret growth patterns, life expectancy, and species variation among large theropods.

Hidden Growth Rings Reveal a Slower Maturation

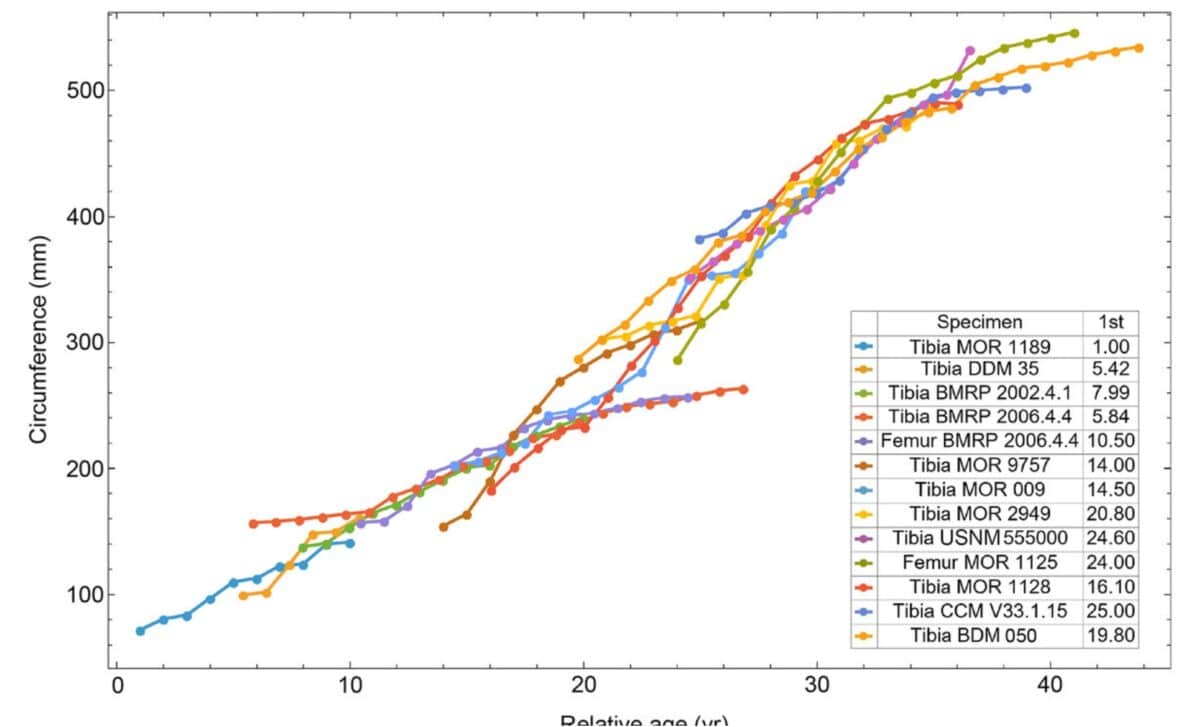

At the core of the new findings is a detailed examination of leg bone samples from 17 T. rex specimens. Using polarized light microscopy, Woodward and her colleagues identified growth rings, similar to those found in trees, that record changes in growth over time. But unlike tree rings, these fossilized growth markers only capture the last 10 to 120 years of life.

Past studies had assumed that T. rex reached full adult size, around eight tons, by age 25. Woodward’s team found otherwise. By examining both visible and previously hidden growth rings, they discovered that weight gain was most rapid between ages 14 and 29. In this phase, T. rex could put on between 800 and 1,200 pounds per year. Yet even after this surge, the dinosaur kept growing, albeit more slowly, for at least another 10 years.

This extended adolescence pushed full physical maturity to as late as 40 years old. Speaking to CNN, Woodward explained: “Instead of growing quickly, T. rex spent most of its life in the mid-body size range rather than achieving a total body length of 40 feet quickly.” The new timeline suggests a prolonged subadult stage, one that likely influenced its role in the prehistoric ecosystem.

Growth Curve Stitched From Multiple Specimens

The researchers applied a new statistical approach developed by Nathan Myhrvold, a mathematician and paleobiologist at Intellectual Ventures, to reconstruct growth trajectories. The method merged data from specimens of different ages to build a composite year-by-year picture of how the dinosaur grew. This helped fill in gaps left by incomplete individual records.

According to Phys.org, Myhrvold’s algorithm reduced the uncertainty caused by densely packed or eroded growth rings, giving scientists the clearest growth curve yet for T. rex. The result is now considered the most comprehensive dataset available for this species. Each data point came from actual specimens, allowing for better comparisons and a more realistic understanding of body size variation, reports Newsweek.

This composite curve not only supports the notion of delayed maturity but also reveals irregular growth rates. “We found that growth ring spacing varied within individuals, with some years showing substantial growth and others very little,” Woodward noted. These fluctuations hint at environmental factors or resource availability influencing how quickly, or slowly, the T. rex developed.

New Evidence Renews Species Debate

Beyond just growth timing, the study’s findings touch on a broader question that has divided paleontologists: is every T. rex fossil really from the same species? The newly observed variability in growth curves and physical development has reignited this debate. Two well-known specimens, nicknamed “Jane” and “Petey,” showed growth patterns distinct from the rest of the sample.

According to Science.org, Lindsay Zanno, a paleontologist at North Carolina State University, praised the study’s methodology, stating, “This study is as good as it gets.” She and others believe the new data may provide the clearest path yet toward understanding whether smaller, more slender specimens like Jane and Petey belong to a separate species, possibly Nanotyrannus, or are simply juvenile T. rex.

Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh who was not involved in the study, said in comments to CNN that the research suggests “more variation among T. rex than we used to think.” If future work confirms multiple species, it could mean reclassifying some fossils that have long been identified as T. rex under a broader “species complex.”

First Appeared on

Source link