Scientists Identified a New Blood Group After a 50-Year Mystery : ScienceAlert

A pregnant woman’s blood sample taken in 1972 was mysteriously missing a surface molecule found on all other known red blood cells at the time.

More than 50 years later, that strange absence finally led to researchers from the UK and Israel describing a new blood group system in humans. The team published a paper on the discovery in 2024.

“It represents a huge achievement, and the culmination of a long team effort, to finally establish this new blood group system and be able to offer the best care to rare, but important, patients,” hematologist Louise Tilley from the UK National Health Service said last year, after nearly 2 decades of personally researching this bloody quirk.

Watch the video below for a summary of their research:

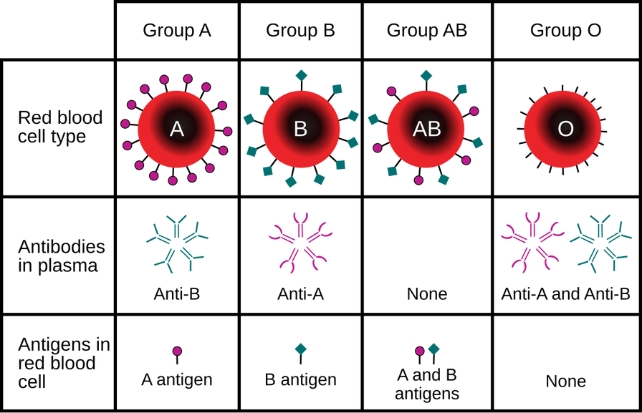

While we’re most familiar with the ABO blood group system and the Rh factor (the plus or minus), humans actually have many different blood group systems based on the wide variety of proteins and sugars that coat our blood cells.

Related: Scientists Identify New Blood Group, And It’s The World’s Rarest

Our bodies use these antigen molecules, amongst their other purposes, as ID markers to separate ‘self’ from potentially harmful ‘not-self’.

If these markers do not match up when receiving a blood transfusion, this life-saving tactic can cause reactions or even end up being fatal.

Most major blood groups were identified early in the 20th century.

Many discovered since, like the Er system first described in 2022, are only found in a small number of people. This is also the case for the new blood group.

“The work was difficult because the genetic cases are very rare,” explained Tilley.

Previous research found more than 99.9 percent of people have the AnWj antigen that was missing from the 1972 patient’s blood. Because this antigen lives on a myelin and lymphocyte protein, the researchers named the newly described system the MAL blood group.

When both copies of a person’s MAL gene are mutated versions, they end up with an AnWj-negative blood type, like the 1972 patient. Tilley and colleagues also identified three AnWj-negative patients without this mutation, suggesting some blood disorders can suppress the antigen.

“MAL is a very small protein with some interesting properties which made it difficult to identify and meant we needed to pursue multiple lines of investigation to accumulate the proof we needed to establish this blood group system,” explained University of the West of England cell biologist Tim Satchwell.

To confirm the culprit gene, after decades of research, the team inserted the normal MAL gene into blood cells that were AnWj-negative. This effectively delivered the AnWj antigen to those cells.

The MAL protein is known to play a vital role in keeping cell membranes stable and aiding in cellular transport. Previous research found that the AnWj isn’t actually present in newborns but appears soon after birth.

All AnWj-negative patients in the study shared the same mutation. However, no other cell abnormalities or diseases were linked to it.

Now that the genetic markers behind the MAL mutation are known, patients can be tested to see if their negative MAL blood type is inherited or due to suppression – which could flag another underlying medical problem.

These rare blood quirks can have devastating impacts on patients, so the more of them we can understand, the more lives can be saved.

This research was published in Blood.

An earlier version of this article was published in September 2024.

First Appeared on

Source link