Scientists Just Uncovered What May Be the Largest Water Reservoir Ever Found—Buried Inside Earth’s Mantle

Earth’s early history is undergoing a quiet revolution. Long assumed to be dry at its core, new research suggests our planet may have formed with a massive internal water reservoir—locked deep within the lower mantle and still influencing geological processes today.

A new study published in Science on December 11 reveals that under extreme conditions, a common deep-Earth mineral—bridgmanite—can store far more water than previously believed. If confirmed, it would mean that the largest body of water on Earth isn’t the Pacific Ocean, but an invisible one buried 1,000 miles (1,609.34 km) below our feet.

Extreme Experiments Point to a Wetter Early Earth

Researchers from the Carnegie Institution for Science, led by Wenhua Lu, used high-pressure, high-temperature experiments to simulate the early Earth’s interior. They relied on a laser-heated diamond anvil cell, reaching temperatures above 3,700 Kelvin and pressures exceeding 700,000 atmospheres—replicating the conditions inside the lower mantle during the solidification of the planet’s early magma ocean.

These conditions revealed that bridgmanite, which dominates Earth’s deep interior, absorbs more water as temperatures rise. The study found an “increased partitioning of water into bridgmanite with increasing temperature,” indicating that significant water may have stayed locked inside the mantle instead of being expelled to the surface.

That key insight was underscored in an accompanying commentary article in Science, which notes that earlier models may have drastically underestimated the amount of water retained in Earth’s interior during the planet’s formative years.

A Deep Reservoir Larger than Surface Oceans?

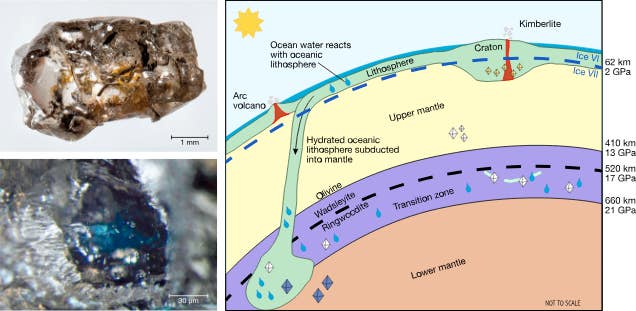

The implications extend far beyond lab experiments. The researchers suggest Earth’s deep mantle may hold water volumes equivalent to several surface oceans. Not in liquid form—but as hydrogen atoms bound within mineral structures, effectively creating a hidden ocean inside solid rock.

If accurate, that would dramatically expand the known global water cycle, which traditionally centers on surface and atmospheric processes. This internal reservoir could help explain chemical signatures in mantle plume volcanism, especially in areas like Hawaii and Iceland, where deep-sourced magma shows characteristics tied to primordial mantle material.

The research also aligns with mounting evidence that Earth’s water is not limited to external inputs. Findings like these suggest the interior of the planet has long served as a water buffer, regulating surface conditions through deep geologic time.

Rethinking Where Water Came From

The dominant theory for decades has been that Earth’s water was delivered late in its formation by comets or carbonaceous asteroids during the Late Heavy Bombardment. But this study bolsters the idea of a “wet accretion” process, in which water was incorporated into the planet from the start—embedded in the building blocks of Earth itself.

That shift carries implications far beyond Earth. If rocky planets form with internal hydration, they may possess latent water reservoirs, even if their surfaces appear dry. For exoplanet research, this broadens the criteria for identifying potentially habitable planets beyond just surface water signatures.

This new view also aligns with emerging models of volatile element retention during planetary accretion. Hydrogen and oxygen could survive inside a forming planet’s interior long after surface conditions turn hostile or unrecognizable.

Inside-Out Habitability

A deep, hydrated mantle doesn’t just shape the early water story—it may still play a major role in planetary evolution. Internal water helps drive plate tectonics, influences mantle convection, and even affects volcanic chemistry. This newly recognized storage capacity turns Earth’s interior into a key regulator of its long-term stability.

The experimental results are just the beginning. Although we can’t directly observe the lower mantle, seismic wave anomalies, xenolith data, and geochemical signatures all hint at lingering remnants of this deep reservoir. As more advanced lab techniques become available, scientists are beginning to map Earth’s interior hydration with increasing precision.

If future models continue to confirm this deep mantle water retention, it could alter our understanding of planetary cooling, geodynamo behavior, and long-term climate regulation.

First Appeared on

Source link