Scientists Now Says Dinosaurs Sounded Nothing like That

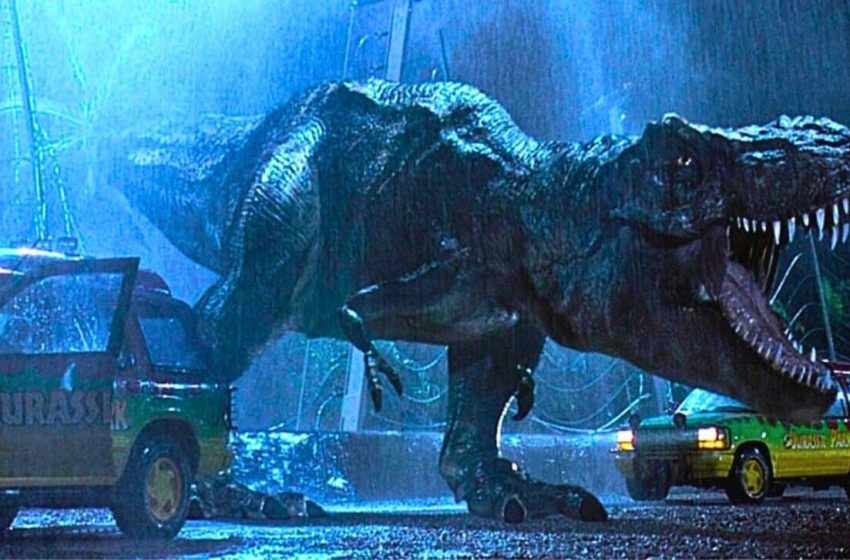

For thirty years, the sound of a dinosaur has been the sound of a baby elephant mixed with an alligator and a tiger. The roar that shook theaters in 1993 became the default setting for an entire prehistoric world, repeated across documentaries, theme parks and children’s toys until it settled into collective memory as fact.

Paleontologists have spent those same three decades trying to correct the record. The problem was always the evidence: vocal cords, larynxes and soft tissues decompose, leaving only bones and teeth for scientists to interpret. Without direct fossil evidence, the debate over dinosaur sounds remained speculative, a battle between anatomical inference and Hollywood’s persuasive power.

That changed in 2023. Researchers published the first description of a fossilized voice box from a non-avian dinosaur, and a second discovery followed in early 2025. The specimens suggest dinosaurs produced sounds closer to a cooing dove or a booming emu than anything resembling a mammalian roar. The anatomical evidence now exists, and it contradicts three decades of cinematic convention.

What Two Rare Fossils Reveal

The 2023 discovery involved Pinacosaurus grangeri, a Late Cretaceous ankylosaur from what is now Mongolia. An international team of researchers described the specimen in Communications Biology, noting that while its larynx shared structural features with modern crocodilians, it also exhibited specialized modifications previously documented only in birds.

The study concluded the dinosaur likely used its larynx as a vocal modifier capable of producing bird-like sounds, despite lacking the syrinx—the complex vocal organ unique to birds. The Pinacosaurus larynx study published in Communications Biology provided the first anatomical evidence that at least some dinosaurs could generate sounds through avian-style mechanisms.

A second specimen emerged from northern China’s Liaoning province in early 2025. Paleontologists described Pulaosaurus qinglong in the journal PeerJ, identifying it as only the second non-avian dinosaur preserved with a bony voice box. The fossil showed vocal structures similar to those of modern birds.

Study co-author Xing Xu, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in the report that it was possible for Pulaosaurus to have avian-like vocalization. The description of Pulaosaurus in PeerJ offers further evidence that complex sound production may have been more widespread among dinosaurs than previously assumed.

These two fossils, separated by thousands of kilometers and millions of years, represent the only direct evidence of non-avian dinosaur vocal anatomy ever recovered. The extreme rarity of such specimens explains why the field of paleoacoustics has advanced so slowly. Paleontologist James Napoli, who studied the Pinacosaurus specimen, told researchers that without such fossils it becomes really hard even to begin to estimate the limits of dinosaur vocal behavior.

Evidence From Living Relatives

A separate line of research published in the journal Evolution in 2016 examined vocalization data from more than 200 bird and crocodilian species—the closest living relatives of dinosaurs. Researchers found that closed-mouth vocalization evolved independently at least sixteen times within this group. The closed-mouth vocalization study in Evolution demonstrated that this trait appears repeatedly across the archosaur family tree, suggesting deep evolutionary roots.

Modern birds including doves, ostriches and emus use this method to generate low-frequency sounds that travel long distances without exposing the caller to predators. The anatomical requirements for closed-mouth vocalization align with the physical constraints of large bodies: bigger animals naturally produce lower frequencies, and keeping the mouth shut during sound production offers clear survival advantages for animals that cannot afford to advertise their location.

The study indicated that large sauropods, ceratopsians and theropods likely used this mechanism to communicate across vast Mesozoic landscapes. Rather than open-mouthed roaring, these animals may have communicated through sounds more analogous to cooing, mumbling or low-frequency booming.

Different Dinosaurs, Different Sounds

For some dinosaur groups, the evidence points to different sound-production mechanisms entirely. Duck-billed hadrosaurs such as Parasaurolophus possessed elaborate hollow head crests that functioned as resonant chambers. Paleontologists have used CT scans of fossil specimens to create computer models of these structures, simulating the sounds they could produce. The results generated calls described by researchers as otherworldly—deep, resonant tones closer to brass instruments than to animal vocalizations.

These findings complicate any single narrative about dinosaur sounds. Different groups likely produced different sounds using different anatomical structures. The hadrosaur crests represent one solution to the problem of sound production; the larynxes of Pinacosaurus and Pulaosaurus represent another. Whether these mechanisms overlapped or remained distinct across dinosaur lineages remains unresolved.

The rarity of preserved vocal anatomy limits what researchers can confidently claim. Cartilage and soft tissue fossilize only under exceptional conditions, which have occurred twice in more than a century of dinosaur paleontology. Scientists cannot determine whether complex vocal abilities were common across dinosaur groups or limited to specific lineages.

The Hollywood Problem

The gap between scientific evidence and public perception remains wide, largely because of Jurassic Park‘s enduring cultural footprint. The famous Tyrannosaurus rex roar was assembled from a baby elephant, a tiger and an alligator—sounds chosen for dramatic effect rather than anatomical plausibility.

Paleontologist Julia Clarke of the University of Texas has addressed this directly. She told reporters the films got it wrong, adding that a Tyrannosaurus rex would not open its mouth to roar, as predators do not advertise their presence before an attack.

Researchers continue prospecting for exceptionally preserved specimens in fossil sites known for soft-tissue preservation. Liaoning province in China and the Gobi Desert in Mongolia have yielded the two existing specimens, and geologists have identified additional formations with similar potential. Comparative studies of living archosaurs continue to refine hypotheses, and computer models of sound production based on fossil anatomy are becoming more sophisticated.

First Appeared on

Source link