Scientists Stumble Upon Mysterious Ancient ‘Wrinkle Structures’ in Morocco That Defy Explanation

Hidden in the rugged landscapes of Morocco’s Central High Atlas Mountains lies a discovery that could change everything we know about the origins of life on Earth. While exploring the region’s ancient rocks, geobiologist Rowan Martindale and her team stumbled upon an unexpected find—bizarre, wrinkle-like fossil structures embedded deep within layers of rock that were once at the bottom of the ocean.

The Bizarre Discovery of Wrinkle Structures in Ancient Rocks

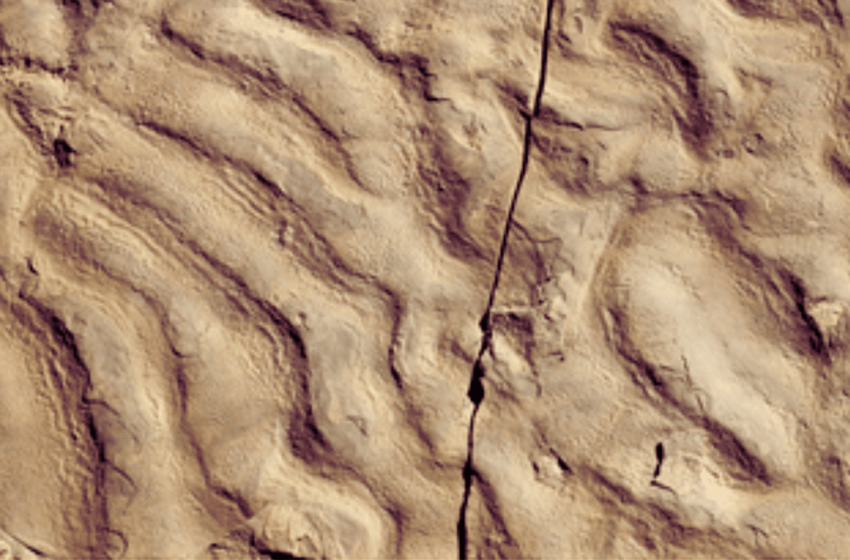

While studying ancient reefs in Morocco’s Dadès Valley, Rowan Martindale, a geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, stumbled upon a fascinating discovery. As she walked across the rocks, she noticed unusual, ripple-like imprints in the sandstone and siltstone beneath her feet. These patterns immediately caught her attention because they resembled microbial mats, delicate, layered communities of bacteria that usually form in shallow waters. However, what made this discovery so puzzling was the environment in which these imprints were found. The fossils were on turbidites, which are deposits formed by underwater landslides. Typically, microbial mats are associated with shallow, sunlit waters, but these fossils were found at much deeper depths, where light wouldn’t penetrate.

This unusual discovery challenged existing theories about where photosynthetic microbial mats could form. “Wrinkle structures,” Martindale said, “are really important pieces of evidence in the early evolution of life.” These findings, published in Geology, suggest that ancient microbes might have lived not in shallow, sunlit areas, but in the deep, dark regions of the ocean, relying on chemical reactions instead of sunlight to thrive.

The Role of Chemosynthetic Life in Early Earth

The wrinkle structures found in Morocco were not formed by photosynthetic organisms, as the researchers initially suspected. Given the depths of the water at the time, sunlight wouldn’t have been available to support photosynthesis. Instead, the organisms that created these structures were likely chemosynthetic, meaning they obtained energy from chemical reactions, rather than from light. Chemosynthetic life is typically found in environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents or around underwater volcanoes, where sulfur and methane are abundant.

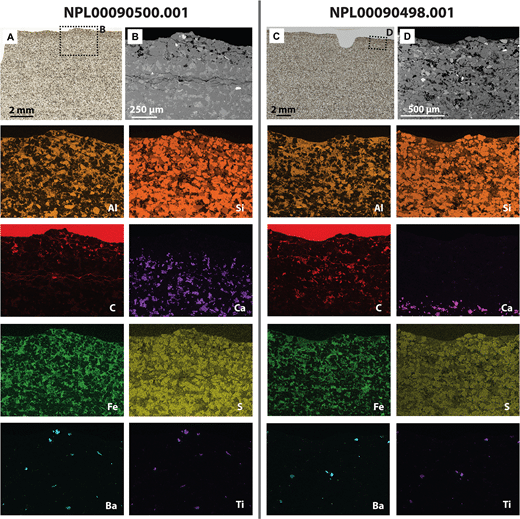

The presence of high levels of carbon in the rock layers further supports this theory. It suggests that these microbial mats were not simply photosynthetic, but rather used sulfur compounds, methane, or hydrogen sulfide for energy. These compounds, created by the decomposition of organic material during underwater landslides, would have provided the perfect energy source for these microbes. Between landslides, microbial mats likely flourished on the ocean floor, only to be buried again by subsequent debris flows, preserving their delicate imprints in the rocks.

Implications for Understanding Early Life on Earth

This discovery significantly alters our understanding of early life on Earth. While microbial mats have traditionally been associated with shallow, sunlit waters, the new findings suggest that life may have been far more widespread and adaptable than previously imagined. “Wrinkle structures” are now considered crucial pieces of evidence in understanding the early evolution of life. They provide insight into how organisms could have survived in extreme environments long before animals appeared on Earth.

The discovery also challenges the assumptions about where scientists should look for the earliest signs of life. If microbial mats could thrive in deep, unstable regions, then researchers may need to widen their search for the oldest signs of life, expanding their focus from shallow formations to deep-water rocks. This could potentially lead to the discovery of even older microbial communities that were previously overlooked.

First Appeared on

Source link