Skynet-1A, a Military Satellite Launched in 1969, Has Been Mysteriously Moved by Unknown Forces

When Skynet-1A launched into geostationary orbit in November 1969, the world was still buzzing from the Apollo 11 Moon landing just months earlier. Built in the United States by Philco-Ford and launched aboard a US Air Force Delta rocket, the satellite was Britain’s first military communications platform, tasked with connecting defense assets from Europe to far-flung outposts in Singapore. It was a bold symbol of British ambition in space at the height of the Cold War.

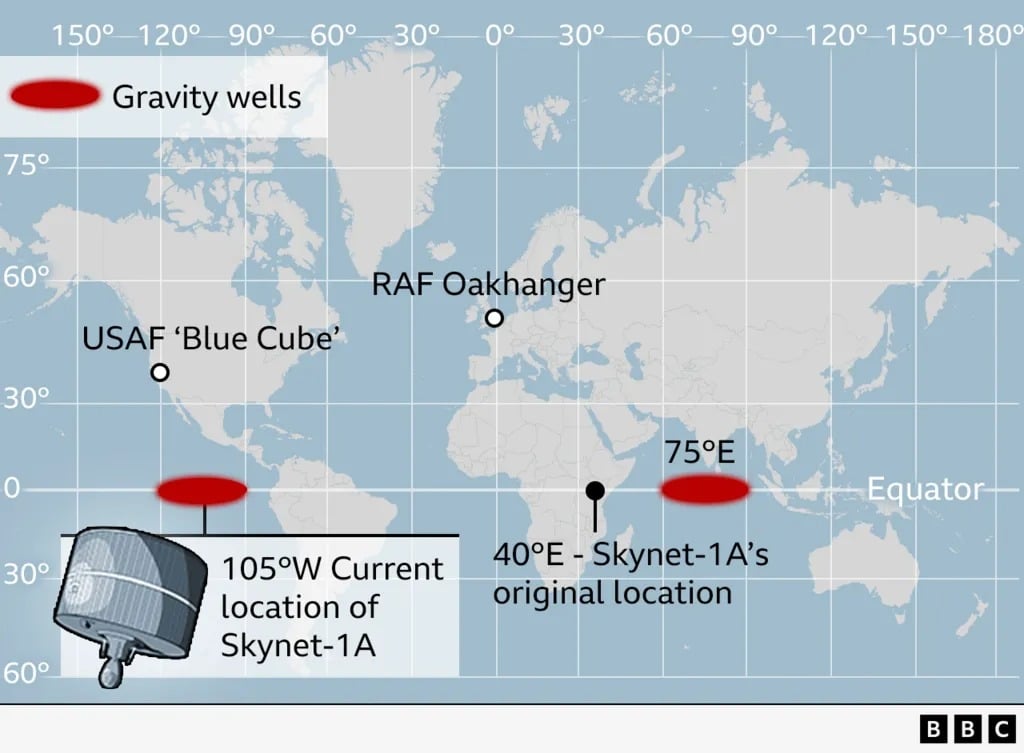

But less than two years after liftoff, Skynet-1A fell silent due to hardware failure. Left inert in orbit 36,000 kilometers above Earth, the spacecraft became space debris—a relic from a bygone era. For decades, its position near 40° East longitude, over Africa, remained unremarkable. Then, in early 2024, satellite trackers noticed something odd: Skynet-1A was no longer where it was supposed to be.

Now drifting near 105° West, over the Americas, the satellite’s new orbit raises serious questions—not just about how it got there, but also about who might have moved it, and why. Orbital mechanics suggest such a shift could not have occurred naturally.

According to Dr. Stuart Eves, former satellite engineer at the UK Ministry of Defence, the satellite appears to have used onboard thrusters—long thought defunct—to maneuver thousands of miles west. “The move defies passive physics,” Eves told the BBC, “which means someone likely commanded it.”

dual controls, lost records

During its short operational life, Skynet-1A was jointly managed by the UK and the United States. While RAF Oakhanger in Hampshire served as the primary control center, technical oversight and emergency operations were periodically handed to the USAF’s Sunnyvale facility—a high-security site informally known as “the Blue Cube.” This arrangement, known as “Oakout,” was designed to maintain continuity during British maintenance windows.

Yet somewhere along the line, the records documenting those operations vanished—or never existed at all. Rachel Hill, a PhD researcher at University College London, has spent the past year digging through National Archives documents in Kew, trying to pinpoint the moment of transfer. “The logs go dark around June 1977,” she noted. “That’s when Oakhanger officially lost contact with Skynet-1A. After that, it’s just gone.”

Her research was outlined in a detailed blog post published by the Global Network on Sustainability in Space, where Dr. Eves also laid out his orbital analysis. One theory suggests the satellite may have been moved during a temporary transfer of control to the U.S., though no definitive records have surfaced to confirm it.

a new problem in old orbit

The puzzle has resurfaced at a time when orbital space is becoming increasingly congested. Today, over 1,000 satellites occupy geostationary orbit, most clustered between 70° and 110° West—prime real estate for telecom, weather, and surveillance systems. Skynet-1A’s current location places it inside what physicists call a “gravity well,” where small oscillations keep it drifting within a narrow corridor—directly in the path of modern spacecraft.

The danger isn’t theoretical. According to NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office, even a collision with a dormant satellite like Skynet-1A could unleash thousands of high-speed fragments. These fragments, traveling at over 11,000 kilometers per hour, could disable or destroy functioning satellites in their vicinity. Under the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, the UK remains responsible for any damage the satellite may cause.

The UK’s official space object registry still lists Skynet-1A as an active item of interest. According to the Ministry of Defence, the satellite is being monitored through the National Space Operations Centre, which issues alerts when it approaches within 50 kilometers of another object. While it has not yet posed an imminent collision risk, experts caution that its age and inability to maneuver make it a growing liability.

tracking the future of space junk

Efforts to clean up Earth’s orbital environment are underway. The UK Space Agency, in collaboration with companies like ClearSpace and Astroscale, is investing in debris removal missions—testing robotic arms, nets, and drag sails designed to de-orbit dead satellites. Most of these are still in early stages, and only a handful are aimed at high-orbit targets like Skynet-1A.

As part of a broader shift in space policy, the UK has signed onto the Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines issued by the United Nations, committing to responsible space stewardship. Yet the Skynet-1A case serves as a sobering reminder: yesterday’s hardware doesn’t disappear—it lingers, often with unresolved ownership and unclear consequences.

Hill and Eves continue their search through declassified files and outdated catalogues, hoping to solve the riddle. But even if the truth is never fully known, the lesson remains clear. In space, as on Earth, neglect carries weight—and sometimes, it drifts silently through the sky for 56 years, until someone finally notices.

References:

First Appeared on

Source link