What are the mysterious lights sometimes seen on the moon?

On the night of April 19, 1787, astronomer William Herschel noted an hours-long light as bright as the Orion Nebula emanating from the unlit, new moon. He had likely witnessed a “transient lunar phenomenon” (TLP) — a short-term change in the appearance of part of the lunar surface.

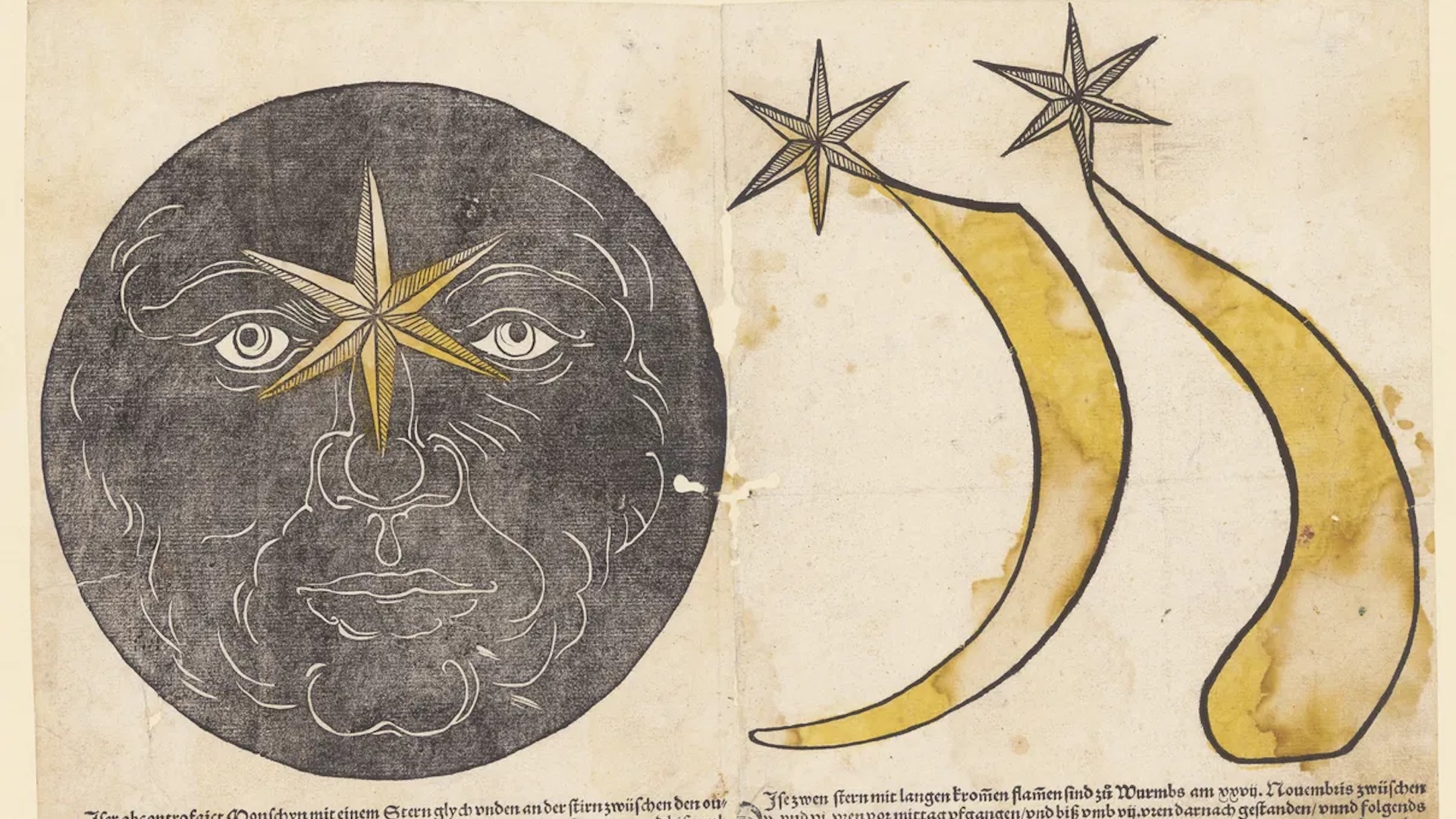

TLPs include brightening, reddish or violet blotches and foggy spots. In fact, some 3,000 TLPs have been documented over the past two millennia by people wielding telescopes, cameras or just plain good vision, said Anthony Cook, a research lecturer in physics at Aberystwyth University in the U.K.

From milliseconds to hours

Superfast flickers — those that last less than a minute — likely occur due to meteoroid strikes, Masahisa Yanagisawa, a professor emeritus at the University of Electro-Communications in Japan, told Live Science in an email. Meteoroids heavier than 0.44 pounds (0.2 kilograms) — about the weight of a billiard ball — produce fleeting flashes of light upon striking the lunar surface. The flashes themselves come from the energy of the impacts that heat rocks on the lunar surface, causing them to glow until they cool.

While such lunar impact flashes (LIFs) were long suspected to be the flickers, scientists couldn’t definitively identify them until in the 1990s, when high-speed video cameras became readily available for lunar monitoring, Yanagisawa said. Yet even then, he added, the flashes’ short duration meant that factors like electric noise within the cameras couldn’t be ruled out.

Confirming a flash, therefore, involved simultaneous observations from two or more distant locations. Despite these constraints, Yanagisawa said, “some flashes were first confirmed during the Leonid meteor shower in November 1999,” which he documented in a 2002 study published in the journal Icarus.

Since then, hundreds more LIFs have been formally recorded by projects like the European Space Agency-funded Near-Earth Object Lunar Impacts and Optical Transients (NELIOTA) program. NELIOTA has recorded 193 LIFs over nine years, and a map of these suggests the flashes occur in specific hotspots, like the Oceanus Procellarum, a lunar region that is potentially tectonically active.

However, the project’s principal investigator, Alexios Liakos, an associate researcher at the National Observatory of Athens, said this apparent pattern is an observational bias. In fact, a 2024 study he co-authored showed that the moon is pummeled “almost homogeneously by meteoroids,” he told Live Science in an email.

In contrast, lunar lights that last minutes may originate in radon gas released from the moon’s interior. A pair of studies published in 2008 and 2009 in The Astrophysical Journal suggest that such outgassing occurs when accumulated gas below the moon’s surface is explosively released by triggers like “moonquakes.” The radioactive radon generates light upon decaying, making it visible from Earth. Plus, spots where longer-lasting lights were observed largely overlap with areas with high concentrations of radon.

But some lights on the moon — like the kind witnessed by Herschel — last hours. Such sightings may be indirectly associated with the moon, according to a 2012 study. The study suggested that the solar wind — the stream of charged particles emanating from the sun — ionizes lunar dust particles, kicking them into enormous clouds 62 miles (100 kilometers) high. These clouds may refract light from stars or other bright objects that appear close to the moon in the sky, ostensibly lighting the lunar surface.

However, some researchers, like Liakos, dispute the existence of long TLPs. “The only longer (and not long) events that I have observed are satellites that cross the lunar disk,” Liakos said, adding that he hasn’t seen any long-lasting TLPs while observing the moon’s night side since 2017.

Still, if you ever see a light on the moon, take note. It could be an illusion of light reflecting off a satellite — but there’s a good chance it’s a TLP.

Moon quiz: What do you know about our nearest celestial neighbor?

First Appeared on

Source link