What Scientists Found in This 3-Million-Year-Old Bone Left Them Speechless

For the first time, scientists have recovered metabolic molecules from fossilized bones dating back up to three million years, opening a new window into the lives, diets, and diseases of prehistoric animals. Published in Nature, this international study explores how bone chemistry can reconstruct ancient environments once home to early human ancestors, providing a remarkable biochemical snapshot of a long-lost world.

Ancient Molecules Trapped in Time

The study, led by Timothy Bromage of NYU College of Dentistry, and published in Nature, explored fossilized bones unearthed across Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, regions significant for their association with early hominins. By applying mass spectrometry to these specimens, researchers detected thousands of metabolites, small molecules tied to biological functions, many of which are comparable to those in modern animals.

Traditionally, studies of fossil remains rely on DNA or collagen to glean insights into species and their relations. But Bromage’s team ventured further, diving into the biochemical realm of metabolomics. “I’ve always had an interest in metabolism, including the metabolic rate of bone, and wanted to know if it would be possible to apply metabolomics to fossils to study early life. It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites,” said Bromage. This groundbreaking approach enabled the team to trace details like diet, health status, and environmental exposure, marking a major advance in how paleontologists reconstruct prehistoric life.

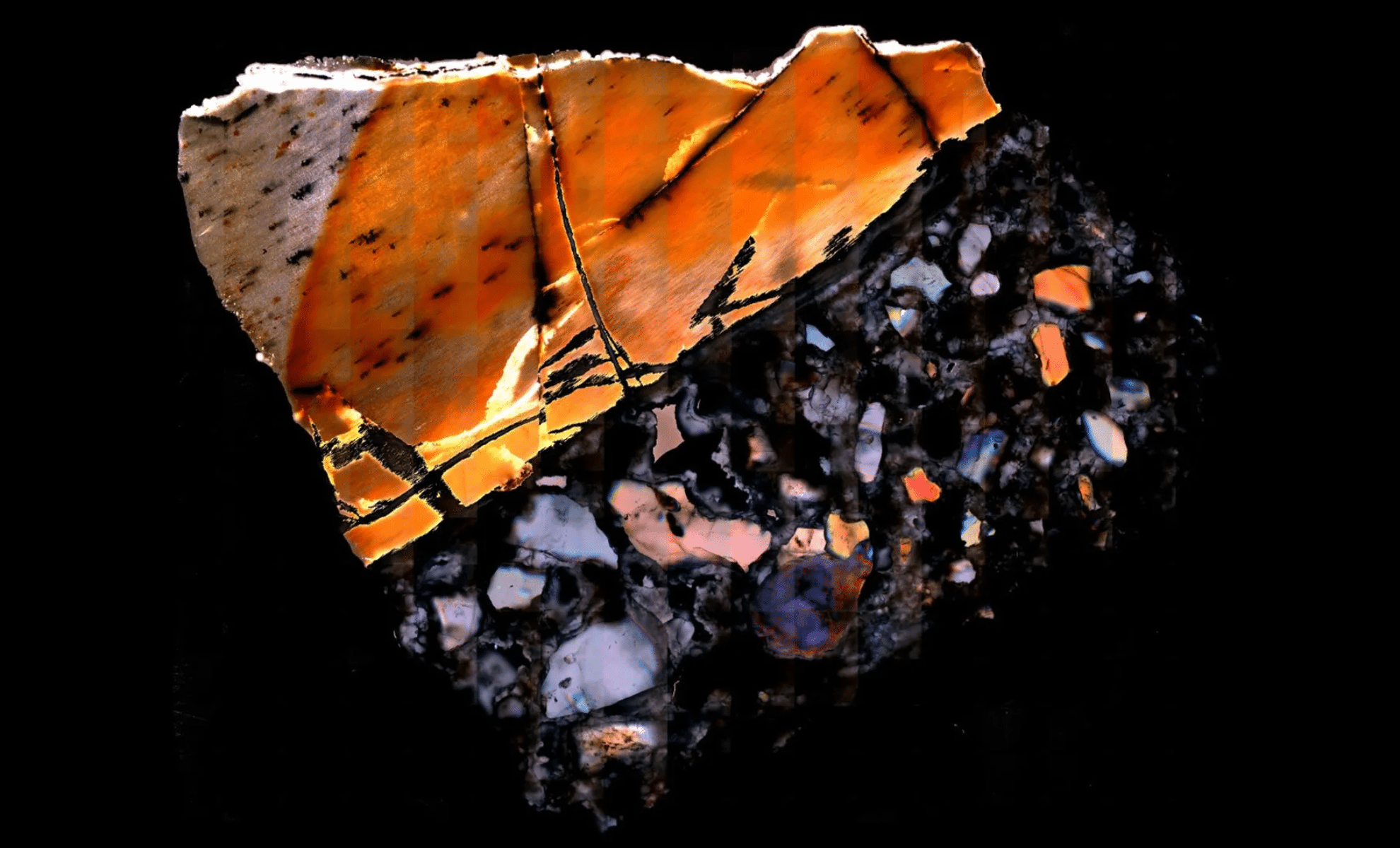

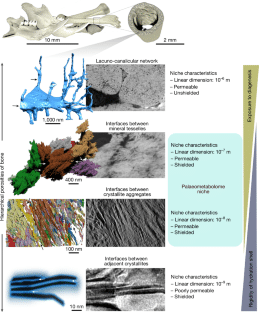

Why Fossil Bones Can Preserve Biochemistry

Fossil bones are more than stone-like remnants. They are porous microenvironments, once interlaced with tiny blood vessels and nutrient exchanges. This internal network may have locked in chemical residues, shielding them from decay over millennia. Previous research had already confirmed the survival of collagen proteins in some fossil bones. Bromage extended this idea, proposing that other molecules, even delicate ones like metabolites, might also be entombed within the bone matrix.

“I thought, if collagen is preserved in a fossil bone, then maybe other biomolecules are protected in the bone microenvironment as well,” Bromage explained. His hypothesis proved accurate. The researchers used modern mouse bones as a baseline and detected over 2,200 metabolites. Applying the same method to fossil samples confirmed their presence in animals that roamed millions of years ago.

This method not only retrieves traces of amino acids, vitamins, and hormones, it also preserves snapshots of illness and dietary intake, creating a multi-dimensional profile of the animal’s last days and the world it lived in.

A Parasite Frozen in Prehistoric Time

One of the most surprising discoveries involved a 1.8-million-year-old ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. Analysis revealed evidence of Trypanosoma brucei, the parasite responsible for sleeping sickness in humans and animals, transmitted by tsetse flies. The squirrel’s body had responded with an anti-inflammatory immune reaction, which was chemically visible in the fossil.

“What we discovered in the bone of the squirrel is a metabolite that is unique to the biology of that parasite, which releases the metabolite into the bloodstream of its host. We also saw the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, presumably due to the parasite,” said Bromage.

This level of disease detection is unprecedented in paleontology, offering new possibilities for studying the evolution of host-pathogen dynamics over geological time.

What Plants Reveal About Prehistoric Climates

Fossil metabolites didn’t just tell scientists what infected these animals, they also revealed what they ate, and by extension, where they lived. The squirrel’s bone chemistry contained plant-based metabolites, including compounds from aloe and asparagus, plants still found in Africa today. These species require specific climate conditions, offering valuable indicators of ancient temperature, rainfall, and soil.

“What that means is that, in the case of the squirrel, it nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream,” explained Bromage. “Because the environmental conditions of aloe are very specific, we now know more about the temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and tree canopy, essentially reconstructing the squirrel’s environment. We can build a story around each of the animals.”

These findings align with prior geological studies, confirming that regions like Olduvai Gorge were once wetter, warmer, and more densely vegetated than today. Each fossil acts like a chemical time capsule, allowing researchers to reconstruct entire habitats with unexpected precision.

A New Era for Paleo-Ecology

This research, published in Nature, establishes a revolutionary approach to studying fossils, not by bones alone, but by the chemical whispers preserved within them. It suggests a future where scientists can decode prehistoric ecosystems down to their climatic and ecological details, using tools from modern biochemistry.

As Bromage summarized:

“Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail, as though we were field ecologists in a natural environment today.”

This integration of paleontology, chemistry, and ecology opens the door to rewriting chapters of ancient life that were once lost to time.

First Appeared on

Source link