What the Smell of Ancient Mummies Reveals About Lost Rituals

Ancient Egyptian mummies have a scent that visitors often describe as woody, spicy, and sweet. Now, researchers are capturing those invisible vapors to uncover exactly how these bodies were embalmed thousands of years ago.

Instead of cutting into wrappings and dissolving fragments, scientists are analyzing the air surrounding the mummies. The results reveal not only the ingredients used in embalming balms, but also how recipes evolved across nearly three millennia of Egyptian history.

For decades, the study of mummification has relied on solvent extraction methods that required removing small samples of bandage, resin, or tissue. Those techniques, while effective, are invasive and sometimes degrade fragile molecules in the process. With limited material available, researchers have had to balance scientific curiosity with preservation.

Now, teams working with museums in Europe and Cairo are turning to volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, microscopic molecules that evaporate easily and carry scent. By analyzing these airborne traces, scientists can link specific smells to fats, waxes, resins, and even bitumen used in ancient embalming practices.

A Molecular Approach to an Ancient Aroma

The distinctive odor of mummies has long intrigued both scholars and the public. A recent sensory study ofnine mummified bodies at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo described their smell as “woody”, “spicy”, and “sweet”, as reported in a 2025 analysis combining human panels and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry.

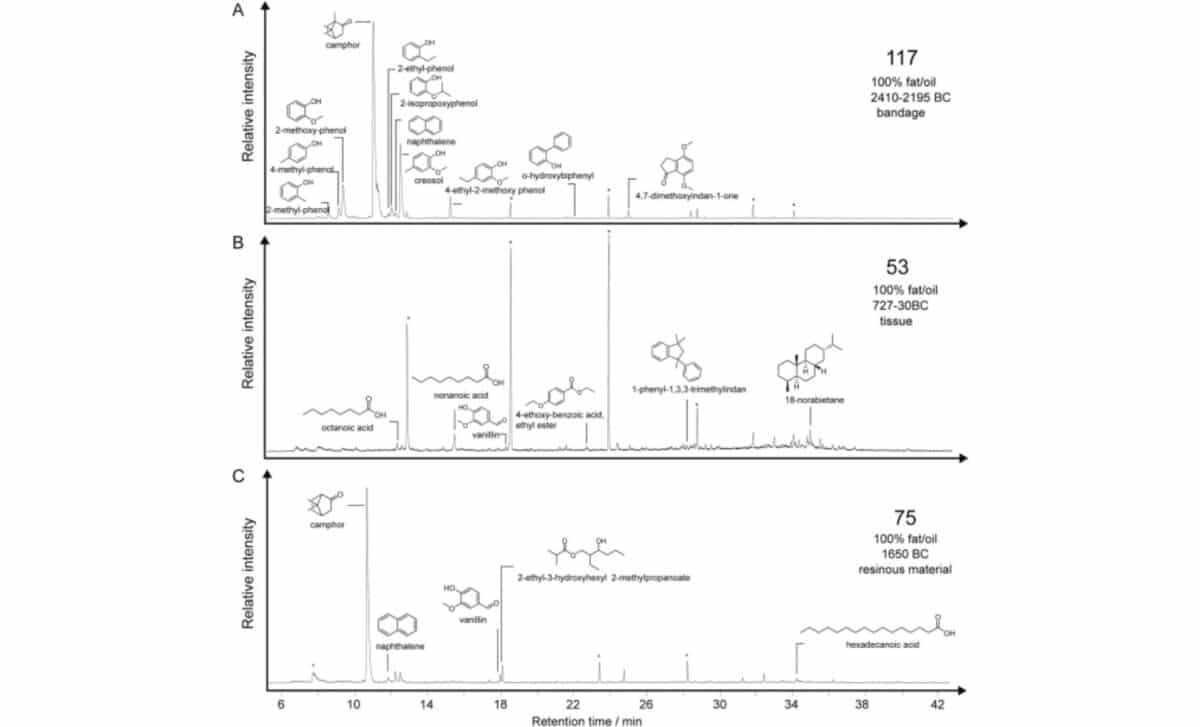

Building on that work, a team from the University of Bristol analyzed 35 samples from 19 mummies dated between around 2000 BC and 295 AD. According to the study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the researchers used headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify VOCs without destroying the material.

Each sample was placed in a sealed chamber and allowed to “breathe,” releasing any lingering volatile compounds. These gases were then chemically separated and identified, revealing biomarkers linked to fats and oils, beeswax, plant resins, and bitumen. The approach provided a minimally invasive alternative to traditional solvent extraction, which can be time-consuming and chemically disruptive.

Recipes That Changed over Three Thousand Years

The chemical signatures tell a story of evolving embalming practices. Early mummies, especially from the Predynastic and Old Kingdom periods, were typically treated with simpler mixtures dominated by fats and oils. Many samples from these early eras showed 100 percent fat or oil compositions.

Over time, the balms became more complex. According to the Bristol team’s findings, later periods incorporated higher proportions of beeswax, coniferous resins such as pine or cedar, and in some cases bitumen. Statistical analyses, including non-metric dimensional scaling and PERMANOVA tests, showed that sample date accounted for the most substantial variance in volatile profiles.

Camphor, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and 18-norabietane were among the compounds that significantly differentiated historical periods. The presence of conifer-related biomarkers suggests the use of cedar or juniper oils, which historical sources indicate were sometimes injected into the body during embalming.

Bitumen, increasingly used from the New Kingdom onward, proved especially distinctive. Even when present in small quantities, its volatile components altered the overall chemical profile. Naphthalene compounds, in particular, were prominent in bitumen-containing samples.

Scent as Science and Belief

Smell was not incidental in ancient Egypt. “Scent played a vital role in Egyptian mythology and afterlife,” researchers wrote in one of the studies. Aromatic substances were used not only to mask the odors of decay but also to protect the body from pests and microbial damage.

The Cairo-based sensory research also identified four main sources of volatile compounds: original mummification materials, conservation oils, synthetic pesticides, and microbiological deterioration products. Terpenoids such as α-pinene and l-verbenone pointed to plant resins and essential oils, while short-chain aldehydes and ketones could signal microbial activity.

Importantly, volatile analysis can distinguish mummies from different historical periods without physical intrusion. As the authors of the Bristol study concluded, “VOC analysis can be used as a rapid, non-destructive, preliminary screening method to obtain useful analytical information without compromising the integrity of the sample or to target samples for more convoluted and time-consuming analysis.”

Taken together, the findings suggest that the scent of a mummy is more than a curiosity. It is a chemical archive, one that preserves traces of ancient trade, ritual practice, and technological skill, still detectable in the air thousands of years later.

First Appeared on

Source link