Why does the same cold virus hit some people harder than others? The nose knows

Dr. Ellen Foxman still remembers her young son struggling to breathe as he battled an asthma attack that tightened his small airways. For any parent, it’s a frightening moment – one that has stayed locked in her memory. But for a scientist, that experience sparked a deeper question.

Foxman knew that her son had asthma. She also knew that a rhinovirus infection, the most frequent cause of colds, can cause wheezing in people with asthma.

“In fact, rhinovirus infection is the most common trigger of asthma attacks,” said Foxman, an associate professor of laboratory medicine and immunobiology at the Yale School of Medicine.

But what interested her was why the same rhinovirus infection unleashed severe asthma attacks and other life-threatening symptoms for some people but barely registered as a sniffle for others.

“Here’s a virus that, in many people who get it, causes no symptoms. Many people who get it get just a cold in their nose,” Foxman said. “Then, for certain groups of people, they get it, and it triggers life-threatening difficulty breathing. … It’s a really interesting virus.”

Foxman and her colleagues at Yale discovered that one key factor behind why some people may experience the same virus differently is how quickly the cells in their noses, called their nasal cells, respond to the virus and contain it.

The body’s quick response, called the interferon response, can vary for different people, and when the response gets inhibited, that can trigger a different reaction, which leads to excessive mucus production and inflammation, according to their study, published in January in the journal Cell Press Blue. Interferons help stop the virus from spreading.

“It’s the body’s response that really determines the disease the virus causes,” said Foxman, a lead author of the study.

Foxman and her colleagues came to this finding when they grew nasal cells from healthy adults in a lab until the cells developed into a community of specialized, interacting cells, similar to what you would find in the average person’s nose.

“They’re real cells, and then if you grow them with the surface exposed to the air for four weeks, they differentiate into a tissue that looks just like the lining of the nose or the lining of the airways of the lung,” Foxman said.

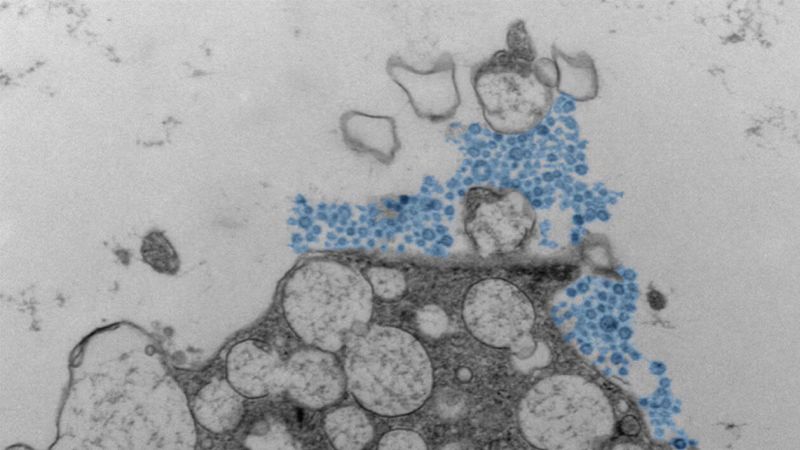

The researchers then infected these cells with a rhinovirus and observed their reactions, using a technique that allowed them to watch thousands of cells at once, specifically examining which defenses were activated in infected and uninfected “bystander” cells.

They found that if the interferon response was activated quickly, it restricted the rhinovirus infection to fewer than 2% of the nasal cells. In a person, that quick response could potentially result in no symptoms of the infection or just a few sniffles, Foxman said.

But when the researchers manipulated the cells to mimic an environment in which the initial interferon response gets blocked, then, “instead of only 1% of the cells getting infected, about 30% got infected,” Foxman said. In that scenario, the researchers also noticed the cells producing a lot of mucus and inflammation.

“So we were basically able to capture both the scenario where the virus is contained, it doesn’t cause much damage, and a scenario where the virus causes a lot of mucus production and inflammation,” she said, which is what would happen during a miserable cold.

But an unanswered question remains: What may cause some people’s interferon response to be weakened or blocked, leading to more inflammation and potentially more symptoms?

Conducting more research in real-life people could help find the answer, Foxman said.

For now, she described the new study as a first step in better understanding what happens in the nose when a rhinovirus infection occurs. It’s possible that in the future, medications could aim to better target the inflammation and mucus production.

The new study is “very informative,” but the findings would need to be confirmed in real-life people with rhinovirus infections to better understand differences in interferon responses, said Dr. Dan Barouch, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who was not involved in the research.

“People might have different levels of the interferon response, and those people who have a higher initial interferon response might only get the sniffles and recover very quickly, whereas people who do not have a robust interferon response would have a much more extensive infection,” Barouch said. “But it’s not entirely clear how someone can improve their own interferon response.”

He added that “although this paper focuses on interferon, there could be other factors too.”

The question of why the same viral infection could affect people differently has emerged frequently in medicine – for nearly all pathogens, said Dr. Larry Anderson, a professor and co-director of pediatric infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the new study.

Although the interferon response can offer clues, other factors that may influence how severely a rhinovirus infection affects a person could include whether there are also certain bacteria present, differences in genetic factors, any underlying illnesses or chronic conditions, and whether a person has prior immunity to the virus due to past infections.

“So there’s a lot of different factors that come into play. And with rhinovirus, someone can get infected with the same rhinovirus and have a different clinical outcome, but that’s the same with influenza, with respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus and coronavirus,” Anderson said. “You see it with a range of illnesses.”

First Appeared on

Source link