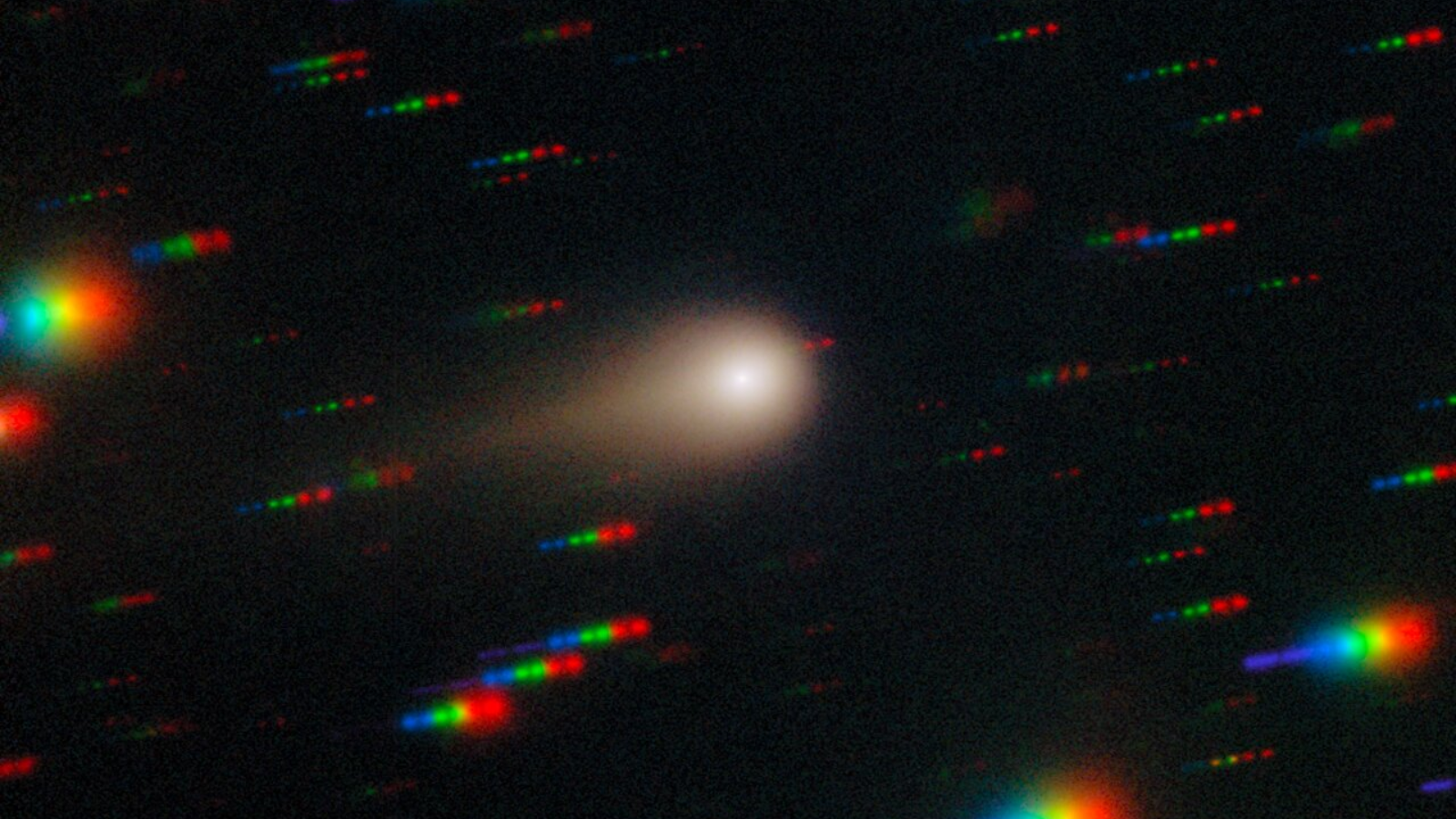

A risky maneuver could send a spacecraft to interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS. Here’s the plan

Scientists think it’s possible for a spacecraft to gain enough velocity to catch up with iconic interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, which is currently speeding away from us, by firing its booster rockets during a very close approach to the sun.

If this mission could launch in 2035, the researchers say, it could at minimum catch up with 3I/ATLAS by 2085 at a distance of 732 astronomical units (AU) from the sun. In other words, that’s 732 times farther from the sun than Earth is, which is 68 billion miles (109 billion kilometers). For comparison, our most distant active space probe, Voyager 1, is currently only 170 AU from the sun after almost the same flight-time as the proposed mission to 3I/ATLAS.

To cross such huge distances so quickly, the mission would take advantage of something called the Oberth effect, named after the Austro–Hungarian rocket scientist Hermann Oberth (who later became a nationalized German and worked for the Nazis). Oberth first proposed the concept in 1929 in his book “Wege zur Raumschiffahrt” (meaning “Ways to Space Travel”).

The idea is that as an orbiting spacecraft falls into a gravitational field produced by a planet or, in this case, the sun, the spacecraft accelerates. At periapsis – the spacecraft’s closest point to the gravitating body — it fires its engines to gain even greater velocity. The Oberth effect describes how doing this when at higher velocities produces a greater change in velocity — what rocket scientists refer to as “delta-V” – and the highest velocities attainable are at periapsis.

“Pretty much every launch uses the Oberth effect,” T. Marshall Eubanks, a former NASA scientist who is now chief scientist at Space Initiatives Inc. and an author of a new paper describing this mission to 3I/ATLAS, told Space.com. “It’s why for example missions such as Artemis 2 do their translunar injection burns at perigee, not apogee. That’s an Oberth maneuver. However, I cannot find a record of a straight-out Oberth maneuver of the type we propose, which is a major rocket burn at closest approach in a flyby.”

As the most massive body in the solar system, the sun is the best place to take advantage of the Oberth effect. But that means getting close — really close.

To achieve a delta-V of at least 5.1 miles (8.4 kilometers) per second, which you can think of as the work required to accelerate a spacecraft onto a new trajectory, the mission would have to perform a solar Oberth maneuver (SOM) at a distance of 3.2 solar radii from the center of the sun. The radius of the sun is 432,450 miles (696,000 kilometers).

Three solar radii equals about 0.015 AU.

Getting this close to the sun, which would be deep inside the solar corona, is not impossible. When NASA’s Parker Solar Probe made its closest approach to the sun in 2023, it came within 0.04AU (3.7 million miles/6.1 million km). Even though this isn’t quite as close to the sun as the proposed 3I/ATLAS interceptor would get, it gives an indication of what would be in store: Parker Solar Probe experienced temperatures of 2,500–2,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,370–1,400 degrees Celsius).

Still, Parker Solar Probe’s heat shield protected it. Adam Hibberd, who is a member of the Initiative for Interstellar Studies and lead author of the research, cites the example of a 2015 design study from the Keck Institute of Space Studies for an interstellar mission that would take advantage of the risky maneuver. The heat shield in the Keck study was a carbon-composite, like the one on Parker Solar Probe, but with added layers of aerogel to further insulate from the sun’s searing heat.

“In principle, a similar heat shield could be used for the mission to 3I/ATLAS,” Hibberd told Space.com.

The solar Oberth maneuver would accelerate the 3I/ATLAS interceptor so much it would become the fastest spacecraft ever, “by a good measure,” said Eubanks.

Hibberd is a software engineer by trade and creator of the Optimum Interplanetary Trajectory Software, which he utilized for this study to determine when would be the most efficient time to launch, given the relevant positions of the Earth, the sun, Jupiter and 3I/ATLAS. He found that 2035 provided the optimum trajectory.

The idea is to first fly out to Jupiter, and use Jupiter’s gravity to slow the spacecraft enough that it is then able to loop back around and fall towards the sun. Though this sounds counterintuitive, it’s necessary. Any spacecraft launched from Earth already possesses Earth’s orbital motion of 18.6 miles (30 kilometers) and at this velocity a spacecraft heading towards the sun would be moving too fast and end up being flung around the sun on a wide orbit rather than get close.

So, the spacecraft needs to shed velocity first. Parker Solar Probe used seven flybys of Venus over seven years to achieve this. Since 3I/ATLAS is racing away from us at 38 miles (61 kilometers) per second, any mission to it doesn’t have time to make multiple Venus flybys, so the 3I/ATLAS interceptor would race out to Jupiter on a journey taking about a year, before heading back towards the sun.

Hibberd, Eubanks and their co-author Andreas Hein of the University of Luxembourg calculate that the spacecraft could have a mass of about 1,100 pounds (500 kilograms), which is about the same as NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto. The mass of the heat shield would have to be deducted from this 500 kilograms – on Parker Solar Probe the heat shield is 160 pounds (73 kilograms).

Separate to this payload would be two or three solid-rocket boosters needed to provide the immense thrust needed at perihelion for the solar Oberth maneuver. The team suggests that several Starship Block 3s (featuring nine Raptor 3 engines) attached to the spacecraft in low Earth orbit before it departs on its mission would be sufficient.

How quickly the mission would reach 3I/ATLAS would depend on the delta-V provided during the solar Oberth maneuver. A delta-V of 5.19 miles per second (8.36 kilometers per second) would enable a fly-by of 3I/ATLAS after a flight duration of 50 years. If we don’t want to wait that long, then if it is possible to get the delta-V up to 6.43 miles per second (10.36 kilometers per second), the rendezvous would take place in just 30 years. This is not impossible — NASA’s Dawn spacecraft to the Asteroid Belt achieved a delta-V of 6.84 miles per second (11 kilometers per second) after separating from its booster rocket.

Because both 3I/ATLAS and the spacecraft would be moving so fast, only a flyby would be possible, rather than entering orbit around the interstellar interloper. This however begs the question, why bother chasing 3I/ATLAS down? Especially as astronomers expect the Rubin Observatory, which has now begun science operations in Chile, to find on average one interstellar comet per year — a big increase on the three that have been identified so far. Very soon there should be plenty of easier targets to reach.

“We’ll just have to see,” said Eubanks. “Maybe after, say, 10 interstellar objects have been found, 3I will seem commonplace and it won’t seem worthwhile to mount an expedition to chase it. But then again, maybe it will seem different and unusual and there will be such a desire.”

3I/ATLAS was well-characterized by astronomers as it passed through last year, and if he had the choice, Hibberd would prefer to see a mission to 1I/’Oumuamua, which was a more puzzling object, instead. In fact, Hibberd has already developed a mission plan for an ‘Oumuamua interceptor called Project Lyra, but feels that the chance to catch it has now slipped away.

Indeed, if we have a mission ready to go, then if we can spot an interstellar comet early enough, more conventional means of reaching it should suffice. This is a viewpoint that was supported by a study from scientists at the South-west Research Institute in 2025.

“For future interstellar objects, a solar Oberth maneuver should be avoided if possible, since it is designed to catch a specific interstellar object ‘after the bird has flown’ and it is heading away from the sun,” said Hibberd. “There are better mission architectures, using a probe already in orbit in space, which would intercept an interstellar object around perihelion in much less time, rendering an Oberth unnecessary.”

The European Space Agency’s Comet Interceptor mission, set for launch either in late 2028 or early 2029, is just such a mission. It will wait at the L2 Lagrange point for a suitable target, either a new long-period comet from the Oort Cloud or an interstellar comet, before being dispatched to rendezvous with it. So, there is a fair chance we’ll have a spacecraft investigating an interstellar comet in the next 10 years.

“I feel quite confident that when we develop the ability to reach these interstellar objects, there will be a strong desire to directly explore at least some of them,” said Eubanks.

That doesn’t mean that the mission profile of a spacecraft taking advantage of a solar Oberth maneuver needs to be discarded. A spacecraft could swing past the Sun to gather speed to head out to explore the outer solar system beyond Neptune.

“Any trans-Neptunian object would be a pretty easy target, and the exploration of those has hardly begun,” said Eubanks.

Additionally, if the theorized Planet Nine is discovered, then it would be so far away, with estimates ranging from 290 AU to 800 AU; a mission to it would likely have no choice but to make use of a solar Oberth maneuver if it wants to get there anytime soon. The maneuver could even be used to send a telescope out to 550 AU from the sun, which is the distance at which the sun’s gravitational field creates a gravitational lens that can be used as a telescope far more powerful than any built so far.

For the time being, 3I/ATLAS continues to speed away from us. Regardless of whether anyone gives chase or not, the development of spacecraft trajectories utilizing solar Oberth maneuvers means that the outermost reaches of our solar system may not be as inaccessible to us as we had feared after all.

Hibberd, Eubanks and Hein’s research is available as a pre-print on arXiv.

First Appeared on

Source link