The Hidden Tumor Trick That Fooled the Immune System for Years

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is among the most aggressive cancers, often described as immunologically “cold” because it provokes little immune response. For years, scientists have known that high levels of the MYC protein drive tumor growth. What remained unclear was how these fast-growing tumors avoid immune detection.

Now, an international team led by researchers at the University of Würzburg, working with collaborators at MIT and Würzburg University Hospital, has uncovered what they describe as a molecular “invisibility switch.” According to the study published in Cell on January 22, 2026, MYC can shift from its well-known role in DNA binding to a separate function that suppresses innate immune signaling.

MYC Shifts from DNA to RNA Under Cellular Stress

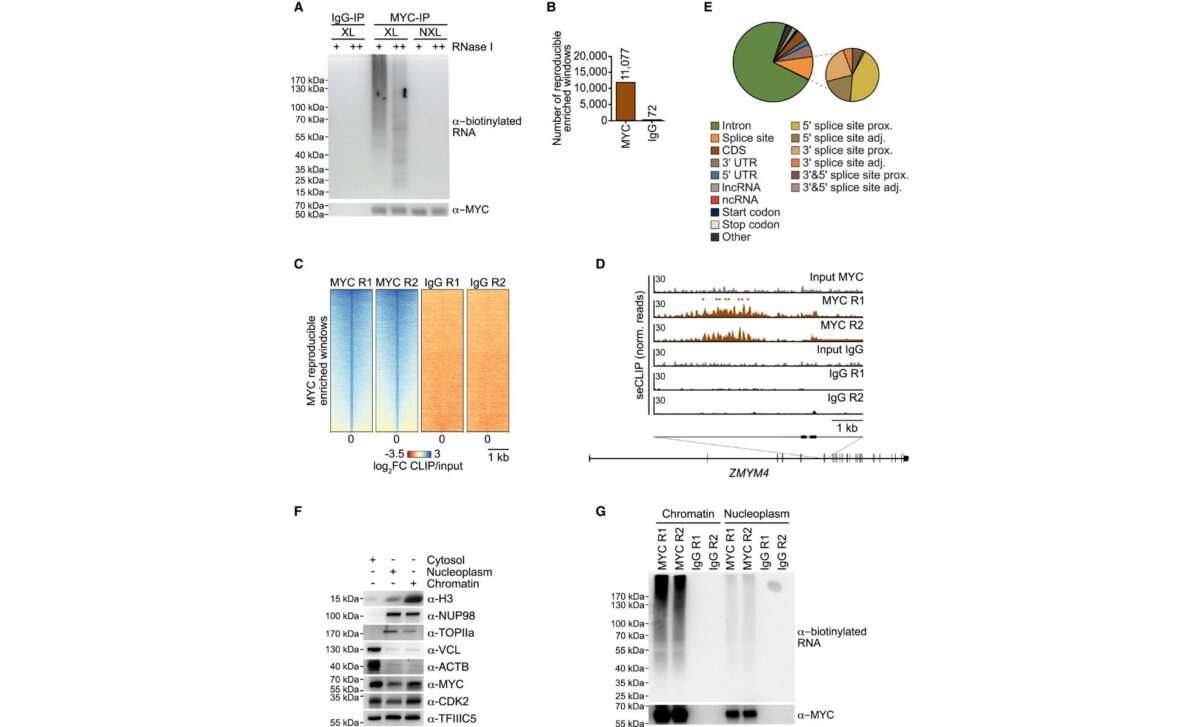

MYC has long been recognized as a central driver of uncontrolled cell division. It forms a complex with MAX and binds to promoters and enhancers across the genome, reshaping gene expression in tumors. Yet the new research shows that MYC does not always stay anchored to DNA.

According to the authors, when transcription is perturbed and intronic RNA accumulates, MYC relocates globally from DNA to nascent RNA. In this RNA-bound state, MYC forms multimers (dense molecular clusters) around double-stranded RNA and structures known as R-loops, which contain RNA-DNA hybrids.

The study demonstrates that MYC contains four RNA-binding regions, labeled RBRI through RBRIV. One region in particular, RBRIII, proved central. It promotes MYC multimerization and enables the recruitment of the nuclear exosome, an RNA-degrading complex, to sites where abnormal RNA structures accumulate. Importantly, this RNA-binding function is mechanistically distinct from MYC’s transcriptional activation role.

Silencing Immune Alarms Before They Sound

Under normal conditions, RNA-DNA hybrids derived from R-loops can activate innate immune pathways. These hybrids are recognized by the pattern recognition receptor TLR3, which in turn activates the kinase TBK1, triggering downstream immune signaling.

The researchers found that MYC, via its RBRIII domain, suppresses this alarm system. By recruiting the nuclear exosome to degrade RNA associated with R-loops, MYC limits the buildup of RNA-DNA hybrids and prevents activation of TLR3 and TBK1.

According to the study, pancreatic tumor cells expressing a mutant MYC protein incapable of binding RNA through RBRIII failed to suppress TBK1 autophosphorylation, a hallmark of TBK1 activation. While both wild-type MYC and the mutant stimulated proliferation in cultured cells, only the wild-type protein repressed gene sets linked to innate immune signaling, including NF-κB and interferon-related pathways.

The difference became even clearer in vivo. In an orthotopic mouse model using pancreatic KPC cells, tumors expressing normal MYC increased in size 24-fold over 28 days. Tumors expressing the RBRIII mutant, by contrast, shrank by 94 percent during the same period—but only in mice with intact immune systems.

Tumor Regression Depends on Immune Recognition

The in vivo experiments underscored a critical point: MYC’s RNA-binding function is dispensable for proliferation in culture but indispensable for sustaining tumor growth in an immunocompetent host.

According to Martin Eilers, senior author of the study, the data show that once the immune system is allowed to recognize the tumor, it can drive tumor regression. Deleting or mutating the RBRIII domain did not impair MYC’s ability to bind promoters or activate canonical MYC target genes. Instead, it disrupted MYC’s capacity to suppress the accumulation of R-loop–derived RNA-DNA hybrids on TLR3.

Further analyses revealed that cells expressing the RBRIII mutant accumulated higher levels of R-loops within genes bound by MYC. These RNA-DNA hybrids were loaded onto TLR3, leading to activation of TBK1 and downstream immune signaling. The authors propose that RNA binding by MYC is a stress response that shields tumors from immune eradication by preventing immunogenic RNA species from triggering innate defenses.

The discovery separates MYC’s growth-promoting function from its immune-evasive role at a mechanistic level. Rather than shutting down MYC entirely, a strategy that has proven difficult due to its importance in normal cells, the findings suggest that selectively targeting its RNA-binding capacity could expose tumors to immune attack without abolishing its transcriptional activity.

First Appeared on

Source link