As Pokémon Legends: Z-A launches, we return to Pokémon Legends: Arceus’ rose-tinted take on the past, and the hard questions it raises about Japanese history

Pokémon has always been a jet-setting series, with its head in the clouds and its feet planted firmly in the real world. The first four generations of Pokémon games took us on a whirlwind tour of Japan. Red and Blue were set in a fictionalised version of Greater Tokyo, with dense cities and urban sprawl. Gold and Silver whisked us down to Kansai, with gorgeous temples and leafy towns. Ruby and Sapphire looked south to subtropical Kyūshū, all seaside cities and swathes of blue ocean. Diamond and Pearl donned their winter coats and flew to the chilly northern island of Hokkaidō, with its craggy peaks and snowfields.

After that, Pokémon went global. Black and White visited New York; X and Y strolled through Paris; Sun and Moon vacationed in Hawaii; and Sword and Shield showed us a mirror-world United Kingdom, where people like Pokémon battles more than football. The Pokemon Legends series even returned to some of these locations with updated graphics and new mechanics. Pokemon Legends: Arceus took us back to Hokkaidō and now, with Pokémon Legends: Z-A, we’re heading to France once more. These regions each have their own made-up names, but their connection to real places is deliberate and palpable.

It’s a brilliant conceit, and the designers have tremendous fun riffing on local creatures and customs. The poké-UK has roly-poly spherical sheep and haunted teapots. The streets of poké-Paris have bouffant poké-poodles. The outskirts of poké-NYC are filled with herds of sentient trash bags. But Pokémon Legends: Arceus, in particular, was different – and as its successor releases into the wild, this is worth revisiting. That’s because, as anyone who played it knows, Legends: Arceus didn’t just transport us through space; it quite literally took us on a journey through time.

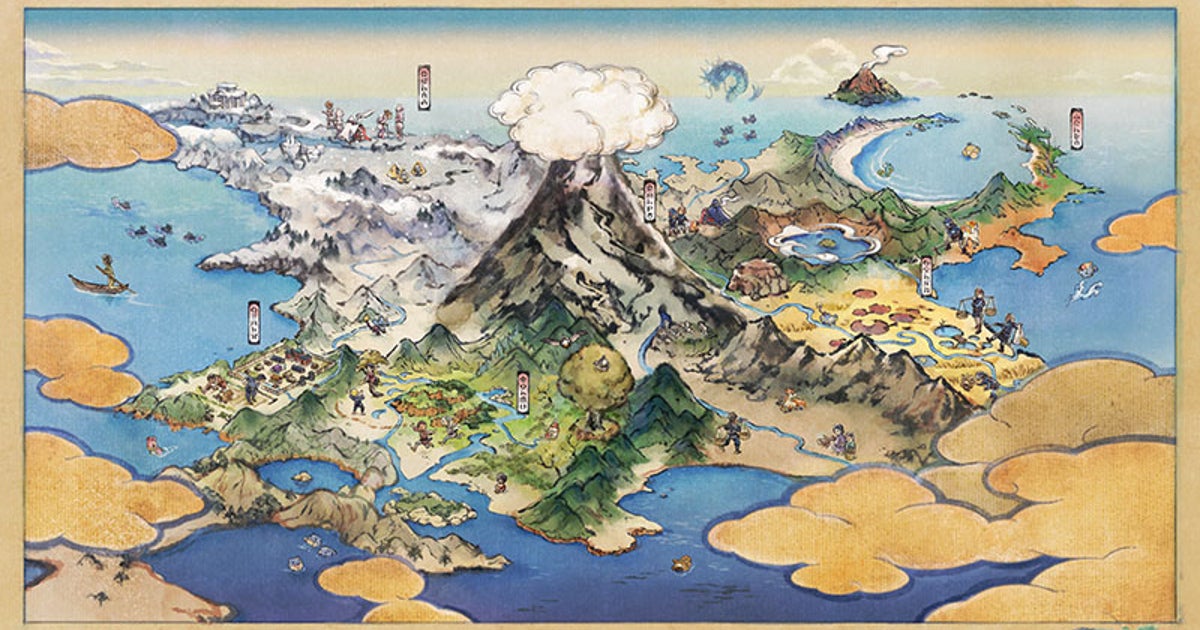

Pokémon Legends: Arceus is set in ‘Hisui’, a reimagining of the northern Japanese island Hokkaido in the late-ish 1800s. You end up there after being mysteriously sucked into a space-time vortex. And this rendering of historical Japan is, mostly, a total charmathon. In Hisui, pokéballs are hand-carved, and loaded with tiny fireworks that crackle and fizz. The battle menus evoke calligraphic brushwork, the skyboxes look like woodblock prints, and the new ‘strong’ and ‘agile’ attack styles are accompanied by the clap of hyōshigi sticks.

Likewise, regional Pokémon designs take cues from Japanese tradition. The Hisuian Decidueye looks like a wandering Ronin, his eyes peeking out from under his wide-brimmed umbrella hat. Samurott sports a dashing red and black samurai helmet. Growlithe is now styled on a Shinto temple lion. It’s a labour of love and, despite the sometimes-muddy graphics, much time and effort have obviously been lavished on getting the setting just right.

But the problem with time travel is that, when we go digging up the past, we sometimes unearth painful memories. Often, these should be handled with serious care.

Pokémon Legends: Arceus takes place during the colonisation of Hokkaidō, when the Japanese government was busily bringing the northern island under its thumb. The game wears its historical inspiration on its sleeve. The central hub area is a bustling frontier town, full of merchants and settlers, which expands as you finish quests. The building where you receive your missions is a facsimile of the Hokkaidō Development Office in Sapporo, the administrative heart of the colonization efforts from 1888 onwards. In one memorable cutscene, settlers arrive on the beach, ready to start their new lives on freshly annexed land. And the game’s primary supporting cast, the Diamond and Pearl clans, are very clearly based on the Ainu, the Indigenous inhabitants of Hokkaidō.

And at this point, anyone even passingly familiar with this period of history might raise an eyebrow. Because the annexation of Hokkaidō was, to be blunt, a tumultuous period, characterised by colonial expansionism and slow bureaucratic cruelty. Unlike the fictional Diamond and Pearl clans, the real Ainu were rarely willing participants in this process. Instead, they were often its casualties.

You see, the Ainu traditionally lived in large part by hunting, gathering, and fishing. Though they also historically practiced cultivation, many and, at times, most Ainu were highly dependent on foods from nature. And it isn’t a bad living. Hunter-gatherer diets are broad, workloads are manageable, and lives are long. But it takes space. It takes clean rivers, and unspoiled habitats for wild animals. It does not easily coexist with intensive farming.

In Pokémon legends: Arceus, Hisui is portrayed as a vast wilderness. And, as a member of the ‘Galaxy Expedition Team’ survey corps, it is the player’s job to survey and explore. But the real-life goal of the real-life ‘Team Galaxy’ – the Kaitakushi, or ‘development commission’ – was not just to explore, but also to displace the Indigenous inhabitants of Hokkaidō and convert their ancestral territories into high-intensity farmland. The real-life Ainu, rather than waxing lyrical about the wonders of Pokémon, instead watched as their land was systematically stolen.

And it gets worse. Not only did the island’s new governors take the Ainu’s traditional territories and hunting grounds, they also orchestrated a campaign of cultural assimilation. This is a euphemistic way of saying they legally defined all Ainu as Japanese citizens, then deliberately, systematically eradicated their language and culture. They outlawed traditional hunting and fishing practices, along with traditional religion and dress. Families were separated and sometimes forcibly married to settlers. Many starved. Even after annexation, the Ainu faced continued discrimination and stigma which endures even to the present day. So successful was this campaign of cultural erasure that, today, only 300 or so people speak the Ainu language, and many have lost touch with their heritage.

The Pokémon Legends treatment is not utterly blind to historical happenstance, of course. Ainu are very seldom depicted in games – their recent appearance in Ghost of Yōtei, Sucker Punch’s Hokkaidō-set action game, being a rare exception – and here in Legends: Arceus they’re portrayed as powerful stewards of nature. The Diamond and Pearl clan’s leaders are all elite Pokémon trainers, and wardens of Husui’s boss-battle ‘noble Pokémon’. Sure, there are a few tired noble savage tropes, which anthropologists like me sometimes grumble about, but it does put Ainu culture and tradition in the spotlight, and gives a generally positive, sympathetic portrayal.

Nor are the Galaxy Expedition Team, for their part, painted as entirely benevolent. At the start of the game, Team Galaxy seems openly hostile and, when Poké-disaster strikes in the game’s final act, rather than helping out, they pin the blame on you, the protagonist, and send you into Poké-exile. By the time the credits roll, though, everyone is very sorry, everything is reconciled, and that’s about as far as the critique goes. Perhaps that’s enough? But considering the actual history, casting the protagonist as the agent of a colonial mission, sent to tame the wilds, is still a thorny path to tread.

Pokémon has always had seams of subtle darkness running deep beneath its family-friendly mantle. Pokémon themselves are weird and otherworldly. Past pokédex entries reveal that, and I quote, Primeape “has been known to become so angry that it dies“. The adorable owl Pokemon Rowlett silently glides close to targets and “pelts them with vicious kicks”. The only person to get a proper look at the disguise-wearing Pokémon Mimikyu was apparently so “overwhelmed by terror” that they “died from the shock”. These macabre morsels add texture and, deliberate or not, Pokémon Legends’ bright and colourful exploration of a grisly time-period certainly keeps pace with the series’ venerated tradition of jarring juxtaposition. But even so, choosing to recruit the player character to the fictional counterpart of a genuine, real colonisation commission, that displaced thousands of people and uprooted thousands of lives? I did wonder if that was a road too far.

Perhaps this is not my judgement to make. Though my brother lives in Hokkaidō, I have never been there. For my day-job, I work in hunter-gatherer communities who have suffered similar displacement and discrimination; but I don’t know anyone with Ainu ancestry, and cannot speak on their behalf. As a UK citizen – a country which hasn’t wholly come to terms with its own chequered history – I am in no great position to tell others how to reckon with the bleaker chapters of their past. It could be that the one-and-a-bit centuries that have passed is long enough to take the sting from these events. And the game does shine a light on a culture that is too often forgotten. But, however you slice it, the game glosses over much historical tumult. This is wise for a children’s game, but was it wise to choose this setting in the first place?

To grapple with these issues, I spoke to Dr John Hennessey, a historian at Lundt University, whose work has explored Ainu colonial experiences and popular representations of imperialism more broadly. He shared my mixed feelings about the game. He agreed that increasing positive Ainu representation in mass media is a praiseworthy trend: “There’s this really, really popular manga series called Golden Kamuy in Japan right now. And the main character is a veteran from the Russo-Japanese war. Then he meets this Ainu girl and they hang out together. She’s super tough and kick-ass” he told me. “The person who wrote this manga, Noda Satoru, went and talked with Ainu representatives and asked ‘How I should depict your culture?’ They said ‘we want to be strong and not just the victims'”. This is something that Legends: Arceus also gets right.

But Dr Hennessey agreed that the game does not always represent the period well: “1969 is the turning point because the Meiji regime started actively colonizing Hokkaidō… They saw it as an important source of wealth for developing the nation; a new source of land… ‘Our wild west’.” These comparisons were quite overt: “They compared it over and over again with America – very self-consciously – and brought in American experts,” Dr Hennessey explains. “That’s the kind of depiction being perpetuated here”, he told me, it’s “the common colonial trope of ‘terra nullius‘ – treating a territory as practically ‘uninhabited’ or a ‘wilderness’ waiting to be explored and claimed, even though it was in fact already inhabited.” And these very same ideas were used to justify settler-colonialism not just in Hokkaidō but around the world.

We also discussed whether the game could have done more to highlight the tragedies of the time-period. Certainly, much of the actual history is too stark for a family-focussed game, but not all of it. For instance: “there used to be huge amounts of salmon and deer. And then they opened canning factories. And within 10 years, they were almost all gone”. Ecological devastation is a topic that is often tackled in children’s media, from the Lorax to Wall-E. Given Pokémon “has a nature focus”, Dr Hennessey continued, this is where Game Freak could have really “planted the seed to get people interested in reading and studying the history”.

Lastly, we explored the role of Western journalists and whether, as outsiders, it is our place to critique another country’s representations of its own history. Dr Hennessey talked about the dialogues happening today in Japan: “there are a lot of lingering stereotypes… they’re working now on improving things and the Ainu have been [legally] recognised twice in different ways,” he said. “But a lot of activists and critical scholars think that Japan is not fully living up to its treaty obligations.”

He told me there’s an open debate about whether “the Japanese government is sponsoring Ainu cultural revival enough”. For example, “when you go to Shiraoi where the Ainu museum is, the trains give announcements in Japanese, English, Korean, Chinese and Ainu… but that station is the only place in Hokkaidō where they did it; and it’s not like this is the only place where Ainu live.” When writing as an outsider, he added, “you have to have a degree of self-criticism” but he also felt that “oftentimes people have blind spots about their own cultures. It can be difficult to study yourself, I think, so there is need for both.” In other words, there is space for internal and external conversations.

Most of all, however, Dr Hennessey felt it was simply valuable to make more people aware of the issues: “It’s really important that these conversations exist, because if they only happen in Japan, then we miss out on them. We need to know about Ainu and Japanese history too!” he said. “If we don’t engage, or are too afraid to talk about these things,” he added, “then we are more likely to perpetuate negative cultural stereotypes.”

And that, more than critique or condemnation, is what motivated me to write this article; because as the Pokémon series once again holds up a twisted Lewis Carrol looking glass to real life, it gives us a valuable opportunity to reflect on a time and place that many of us have never considered. Perhaps it’s sensible that the newest game in the series, Pokémon Legends: Z-A, returns to the modern day; yet if Game Freak’s team decides to make a third Legends game, I hope they’ll do the time warp again. Perhaps they’ll get it right, perhaps they’ll get it wrong. In either case they’ll give us another opportunity to learn about history through that same colourful, distorted lens.

First Appeared on

Source link