Corporate America struggles to respond to killings in Minnesota.

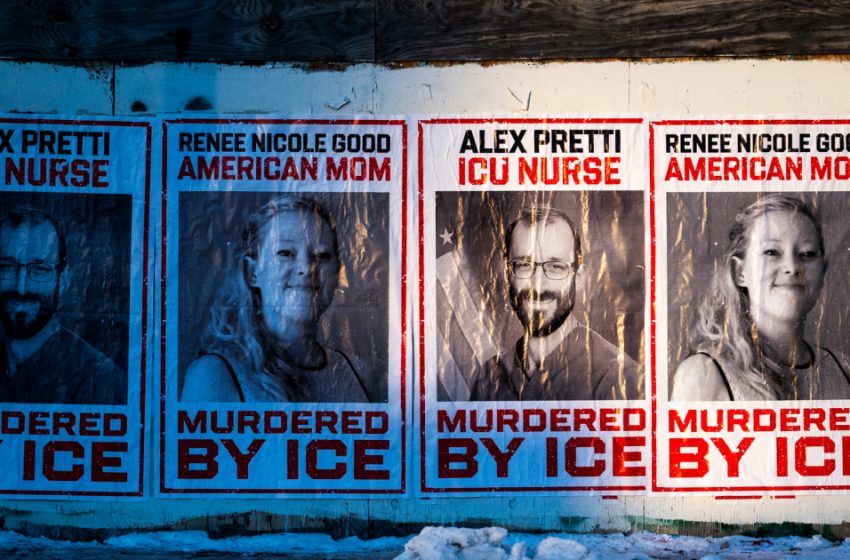

In the wake of Alex Pretti’s death at the hands of federal officers in Minneapolis, a growing number of corporate leaders, employees and Minnesota-based companies are speaking out. Some are condemning the fatal shooting and President Donald Trump’s broader immigration enforcement in the state.

But the response has also exposed a familiar tension in corporate America: Powerful executives and public-facing companies often stay quiet until internal and external pressures converge — and until they believe speaking out together matters more than speaking loudly.

“What’s really interesting is that the CEOs do engage when they get to a tipping point, and we’re at one again,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a Yale School of Management professor and author of the book “Trump’s Ten Commandments.”

He pointed to moments such as the deadly 2017 white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 as examples of crises that forced high-profile executives to move collectively.

“CEOs have to periodically speak out not on every issue but when there are watershed moments where there is a tipping point where the fabric of society is put at risk,” Sonnenfeld said in a phone interview.

Following the killing of Pretti in Minnesota, a small number of tech and financial industry leaders moved quickly. Hemant Taneja, CEO of the venture capital giant General Catalyst, appealed to his colleagues “to come together to preserve our democracy,” writing on X that “what we are seeing in Minnesota is a threat to those core tenets and to the promise of America.”

Anthropic co-founder and leading AI researcher Chris Olah wrote on his personal X account, “I try to not talk about politics … but recent events — a federal agent killing an ICU nurse for seemingly no reason and with no provocation — shock the conscience.”

Leaders of larger companies have moved more slowly. After weeks of relative silence from major employers in Minnesota following the fatal shooting of Renee Good in early January, more than 60 CEOs of companies based in the state, including Target, UnitedHealth Group, Best Buy and 3M, released a brief joint statement Jan. 25 calling for an “immediate de-escalation of tensions.”

The letter urged “the Governor, the White House, the Vice President and local mayors” to “work together to find real solutions,” although it stopped short of calling for specific actions.

Critics argued the letter did not go far enough because it did not mention immigration or directly condemn the shooting of Pretti.

But Sonnenfeld pushed back against the idea that sharper language would have been more effective.

“Whether or not they call for de-escalation or actually call the shooting a murder is inconsequential if it buys them the force of 60 CEOs rebuking the Trump administration,” he said, arguing that executives were trying to maximize unity rather than escalate rhetoric or pick a fight with the White House.

Sonnenfeld pointed to a line he attributed to the civil rights leader Andrew Young as a guide for how CEOs think about persuasion in moments like this: “You can’t reach an alcoholic by calling them a drunk.”

“The only way you counter a bully is through collective action,” Sonnenfeld continued. “That’s a cautionary tale for CEOs not to speak out alone but to speak out together.”

That dynamic has played out repeatedly during the Trump era, as executives weigh the risk of drawing political retaliation against the risk of saying nothing as events escalate.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, recently, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon was asked about chief executives’ reluctance to publicly challenge the administration.

Dimon said he agrees with some of Trump’s policies but not others. “I’m not a tariff guy,” he said, adding, “I think they should change their approach to immigration.”

“I don’t like what I’m seeing, with five grown men beating up little women,” Dimon continued, without mentioning a specific incident. “So I think we should calm down a little bit on the internal anger about immigration.”

The hesitation among high-profile executives has not stopped employees from speaking out. Since Pretti was killed, more than 800 tech workers signed an open letter saying, “We condemn the Border Patrol’s killing of Alex Pretti and the violent surge of federal agents across our cities.”

That history has informed how executives approach moments like Minnesota, Sonnenfeld said.

For some companies, previous instances of backlash have reinforced the need to move carefully and collectively.

Minneapolis-based Target Corp. has repeatedly found itself at the center of cultural and political controversies. In 2023, the retailer drew fierce backlash after it pulled its Pride Month merchandise collection off store shelves.

Target came under fire again last year, after it rolled back elements of its diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives. Calls for boycotts and lawsuits led to a slowdown in nationwide traffic to its stores.

Disney faced similar backlash after then-CEO Bob Chapek publicly denounced Florida’s “don’t say gay” law, a move that triggered a prolonged political standoff with the state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis. The episode became a cautionary tale for top executives weighing whether to take public stances on charged policy issues.

At the same time, Sonnenfeld said, the cost of staying quiet has also risen, particularly inside companies with highly mobile workforces.

The risk of so-called brain drain, or the loss of highly skilled employees to competitors when leaders decide to stay silent about policy issues their employees feel strongly about, is “significant,” he said.

Nonetheless, executives have good reason to be selective about when — and how — they act.

“Corporate America has found that silence is not golden,” Sonnenfeld said. “But they also know [that they] have to keep their powder dry. They can’t pick every issue, or they lose their effectiveness, and they also can’t speak out alone, or they suffer Trump’s vindictiveness.”

First Appeared on

Source link