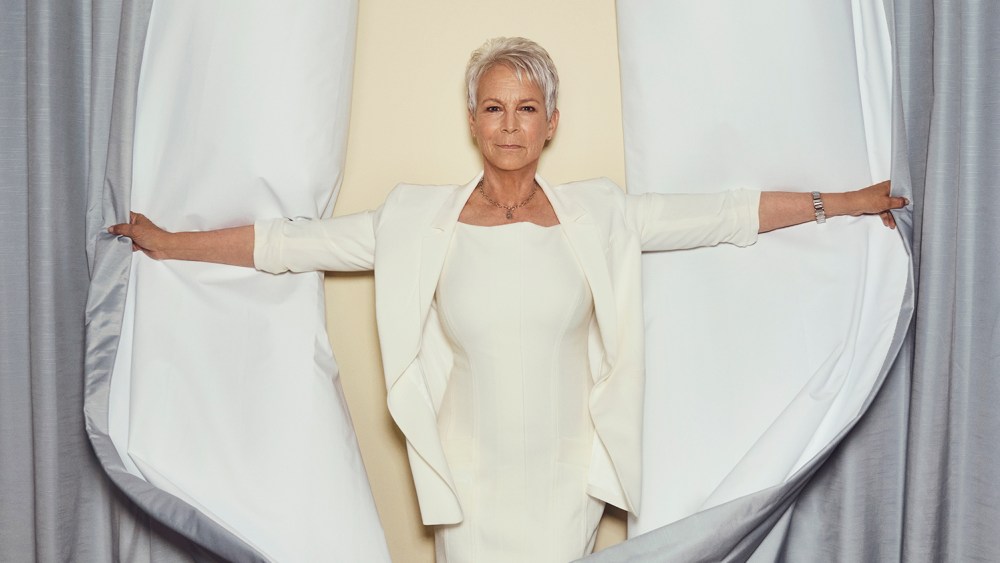

Jamie Lee Curtis on 47-Year Acting Legacy and Charlie Kirk Backlash

When Jamie Lee Curtis was shooting “Fierce Creatures” in London in 1996, Princess Diana came by the set with her two little princes.

It had been a long day, and Curtis was on a much-needed pee break when the royal family arrived. Unfortunately, by the time she made the mile-long journey back from the bathroom in her golf cart, Diana and the boys were gone. So Curtis wrote the princess a letter, which she left at Kensington Palace, saying how sorry she was not to have met her, and how much she admired her. Curtis explained about the long day and the bathroom break and the golf cart.

“Diana wrote back,” Curtis says today from her porch overlooking a lush Santa Monica canyon. “She was like, ‘Totally get it: Been there, done that. I admire you too. It’d be nice to meet you someday.” Curtis barely pauses and says, “She died a year later.”

Sami Drasin for Variety Magazine

There is banana bread that Curtis made “in the dark” early that morning and small, foamy cups of strong cappuccino. There is a little white dog, Runi, whom Curtis talks to in a high-pitched voice. Later, she’ll sign 15 children’s books she’s written over the years and put them in a tote for my 3-month-old grandson. Curtis is, I would say, proudly domestic and aggressively generous, sometimes in a hoovering mother kind of way. (On my way out, she’ll ask, “Do you need to pee or poop before you go?”)

The day that Princess Diana died, Curtis sat on her bed in this same house, where she lives with her husband of 41 years, Christopher Guest, and instead of watching, on a loop, the televised images of the tunnel where Diana was killed, she turned off the TV and picked up a book by Insight Meditation guru Jack Kornfield that a friend had given her. “The opening pages say that anyone who has tried to live mindfully at the time of their death asks themselves two questions: Did I learn to live wisely? Did I love well? And I remember sitting there and thinking about Diana’s life, and about her getting out of this bullshit marriage; her bravery at the beginning of the AIDS crisis when she reached out to a man with AIDS and put her hand on his leg; her walking through those minefields. Just her beautiful humanness. And I thought, ‘She learned to live wisely. And yeah, she loved well.’ That has stayed with me.”

Curtis is thinking about the spectacle of Diana’s death, because yesterday she was on Marc Maron’s “WTF” podcast talking about her new movie, “Freakier Friday,” and plugging “The Lost Bus,” which she produced with Jason Blum, when she and Maron got onto the subject of Charlie Kirk, the Christian nationalist who’d been assassinated a few days before. Probably because she has been a longtime advocate for LGBTQ rights (her daughter Ruby is trans), no one expected Curtis to cry about the death of a man who said, “The transgender thing happening in America now is a throbbing middle finger to God.” And not everyone understood how she could say she hoped his god had been with him at the moment of his passing.

So the backlash over the interview was fierce, relentless and “threatening.” “An excerpt of it mistranslated what I was saying as I wished him well — like I was talking about him in a very positive way, which I wasn’t; I was simply talking about his faith in God. And so it was a mistranslation, which is a pun, but not. In the binary world today, you cannot hold two ideas at the same time: I cannot be Jewish and totally believe in Israel’s right to exist and at the same time reject the destruction of Gaza. You can’t say that, because you get vilified for having a mind that says, ‘I can hold both those thoughts. I can be contradictory in that way.’”

Being a public figure, she must have to be careful, I say, and she sits up straight and glares at me.

“I don’t have to be careful,” she says sharply. “If I was careful, I wouldn’t have told you any of what I just told you. I would have just said, ‘Hi, welcome. I baked you banana bread. Here’s my dog. Here’s my house, blah, blah, blah. What do you want to know?’ I can’t not be who I am in the moment I am.”

It takes an iconic royal to know an iconic royal. At 66, Curtis downplays her childhood with her famous parents, Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, saying that she had a “comfortable, not fancy” L.A. life with her mother and Marine stepfather after her father “abandoned” the family for a 17-year-old. She says: “Show business wasn’t evident to me as a child. I mean, there are a couple pictures of me on sets with my sister, but I don’t have a memory of any of it — any of it, just none of it.”

But the fact is, whatever powerful juju ran through her parents’ veins was passed on to their daughter, so much so that she’s been a part of the American consciousness since she was 19, when she headlined “Halloween,” the template-setting slasher film. Furthermore, she’s remained that famous for the next 47 years and counting, winning an Oscar and an Emmy late in her career.

But back when she was a kid, she thought of herself as someone with “no tangible abilities: I was a D+ student — C- if you graded on a curve. I was a cheerleader.” She’s holding a bit of banana bread between her fingers as Guest pads around the kitchen in bare feet behind her. “I was kind of a weirdo. I was” — she points to herself — “this girl at 16, full of energy and personality. But I had no intelligence. You know, I wasn’t an athlete, I wasn’t in the plays. And I became an actor by accident.”

Curtis credits a series of strong women with helping her evolve from an “incurious” child to a person with a formidable mind and an uncanny ability to raise money.

She starts with her mother — most famous for her part in “Psycho”— who, when Curtis was a little girl, joined a group called Share, started in the 1950s by the wives of Hollywood stars to raise money for children’s causes in L.A. Part of Share was an annual star-studded show called the Boomtown Party. Curtis watched rehearsals at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium every year, and it stuck with her, seeing her mother don a cowboy outfit and dance with Steve McQueen’s wife, Neile Adams McQueen; and Altovise Davis, who was married to Sammy Davis Jr., all to support kids less fortunate than herself.

Being friends with Eunice Kennedy Shriver, Curtis’ mother was also involved with the Special Olympics at UCLA, which Shriver started in 1968. “This was the beginning of the Special Olympics at UCLA,” Curtis says, “and celebrities would come to walk the opening ceremonies. Curtis and her mother went every year.

“I raised my hand when I was 15,” she says. “What if we call Polaroid and get them to donate cameras? I’ll set up a booth, and then we can take Polaroids of the athletes with a celebrity and give them the Polaroid.”

Shriver liked the idea, and Curtis ran the booth for years. “Four years into it, when I was 19, Eunice called me and said, ‘We’d like you to be in the pictures this year, because you were on TV.’”

About that television appearance.

When she was home for Christmas break after her first semester at college, Curtis visited a friend in Beverly Hills. The friend had a tennis court where her family took lessons from a guy named Chuck Binder. He called out to her from the court, “Hey, Jamie!”

“I knew him for years,” she says. “And it was like, ‘Hey, Chuck.’ And he was like, ‘They’re looking for Nancy Drew at Universal. I’m managing actors now.’” Curtis interrupts herself to say, “Show business, right? You’re a tennis teacher; now you’re managing actors.” Then she continues her story: “He goes, ‘You should go up for it; you’d be good.’ I was like, ‘OK.’”

Curtis auditioned for “Nancy Drew” and didn’t get the part, but it gave her an idea: What if she did a monthlong independent project where she’d try to break into show business and write a paper about it? She called someone at the school, and they agreed.

A few days before she was scheduled to go back to college, Binder sent her to audition for Monique James, who was the VP of new talent at Universal Studios. (“Women get shit done,” Curtis says of James.) Curtis brought in a kid from acting class, and they did a scene, and when they were done, Curtis turned to James and said (she does this like she’s a gum-chewing airhead): “Hey, listen, this was fun. Thank you so much. I loooved it. Listen, honestly, here’s what the problem is: I’m going back to college in two days, so I need to know if this is going to happen.” She drops the airhead shtick. “They called me the next day, and they offered me a contract. I dropped out of college and became an actor, bringing in $235 a week.”

Curtis moved into a stucco-ceilinged one-bedroom apartment on Mary Ellen Avenue in the Valley, furnishing it with the wicker bedroom set from her childhood and a Naugahyde couch. She got bit parts on “Quincy, M.E.,” “The Hardy Boys” and “Columbo,” and then she snagged a role on both the film remake and the TV show “Operation Petticoat,” about Army nurses who get stuck on a Navy submarine.

Then James invited her to lunch and told her she was fired; ABC was revamping the show, and she was one of 11 actors to be let go. Curtis drove home to her “shitty little apartment, thinking, ‘Oh, fuck, I’m gonna have to move home. I’m gonna have to go back to college!’”

A week or so after that, Binder called. “They’re casting this low-budget horror film out of an office on Cahuenga,” he said. “The director is up-and-coming.” That director was John Carpenter, and the film was “Halloween.”

“If I hadn’t gotten fired,” Curtis says, “I would have never auditioned for ‘Halloween,’ which then became something important, right? And then the rest of my life happened.”

We’ve all watched her films over the decades: Maybe we saw the early run of horror films that made Curtis the ultimate final girl and gave her the title of “scream queen.” Many of us have seen “Trading Places,” “A Fish Called Wanda,” “My Girl,” “True Lies,” “Freaky Friday,” “Knives Out,” her return to “Halloween” and “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” for which she won a supporting actress Academy Award. Her nearly five-decade-long path to Oscar winner has been a part of our cultural identity: She is such a force that she replaced then-all-American hero O.J. Simpson as the person running through airports jumping over things for Hertz.

Then, in 2023, she stunned us with her deep, raw, Emmy-winning performance as Donna Berzatto, the alcoholic Italian matriarch of an irrevocably damaged family on “The Bear.” She had never met anyone in the cast when she came to shoot the episode called “Fishes,” where she’s drinking and smoking and terrifying her people while cooking a doomed Christmas dinner.

“Jamie came in swinging,” says Christopher Storer, the creator of “The Bear.” “Normally, we’re not the type of show that tries to get famous people — it’s always friends of ours. And Jamie was the only one that was outside of that, because we knew we needed danger — we needed a wild card that the cast wasn’t familiar with. And the first time really anyone met her, she was Donna. Our call time was at 7, and at 7:02 we were shooting in the kitchen, and she was putting butter in her hands, wiping it across baguettes. She’s an animal. She’s a fucking animal.”

And she’s not slowing down. “Freakier Friday” came out in theaters in August, and “The Lost Bus” was released in September. Her next film, “Ella McCay,” a political comedy-drama written and directed by James L. Brooks and starring Emma Mackey, is coming to theaters on Dec. 12.

But Curtis is not just ferocious on set; interpersonally, she’s also what Storer calls “a tiger.” In 1984, for instance, when she saw a photo of Guest in a magazine, she turned to her friend, the late “Halloween” producer Debra Hill, and said, “I’m going to marry him.” Curtis thought he was “cute.” Hill said, “Oh, yeah, I tried to put him in a movie once — his name is Chris Guest. He’s with your agents.” The next day, Curtis called her agent and asked him to pass her number on. The agent did, but Guest never called.

Then, a couple months later, Curtis was having dinner with Melanie Griffith and her and her then-husband Steven Bauer at Hugo’s in West Hollywood, and Guest was there, two tables away, facing Curtis. “He kind of looked at me, and he was like,” she does a shy little wave, “like, ‘Hi. You called me.’ And I made the gesture of —” she does the shy wave back, “Like, ‘I’m the asshole who left my number with our agent.’”

Five minutes later, Curtis says, Guest got up to leave. “And he stood at his table,” Curtis says, “10 feet, 15 feet away, and he sort of went,” Curtis shrugs her shoulders, “and I went—” she shrugs again. “And he left. He didn’t come over.”

Guest called Curtis the next day, and five-and-a-half months later they were married. She was 25 years old.

But Curtis’ grounding in philanthropy remains key to her identity. In 1984, while she was shooting “Grandview, U.S.A.” in Pontiac, Illinois, the town put on a benefit for Lori Tull, the first successful teen heart transplant patient. The cast and crew joined the event, and Curtis sold kisses at a fair and befriended Tull. They stayed in touch, including when Tull had her second transplant at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Around this time, Curtis had a friend who was dying of AIDS at Midway Hospital in L.A. He had a VCR in his room, and when Curtis visited, they’d watch movies. “I remember him saying, ‘Let’s watch “Casablanca,”’” she says. So when Tull died, at 20, Curtis knew how she could honor her: She went to all the studios and asked for their backlog of videotapes. “I put videotape machines in the rooms at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh in Lori’s name, and then had a rotating library of videotapes put in, because I understood the power of distraction.”

Curtis went back to Children’s Hospital to fundraise every year after that, and the hospital eventually created a chair in pediatric transplantation in her name.

“Talk about waking up feeling gratitude and grateful for a life,” Curtis says, her plate of banana bread now only crumbs, her coffee cup empty. “How the fuck did I end up here?” she says, gesturing to the green treetops and flawless blue sky before her. “I was in a one-bedroom stucco apartment on Mary Ellen Avenue, and now I’m all of a sudden here with you.”

Have you lived your life wisely? I ask.

“Yeah, for sure. Yeah, for sure,” she says, nodding vigorously. “Oh, my God, for sure!”

Have you loved well?

“Way well,” she says. “Way well.” She adds, “But I still recognize how difficult life is for most people. I think, ultimately, the root of philanthropy — and the root of humanity — is the relationship between your understanding of the reality and then your reality. How do you reconcile the two? That’s service.”

Hair: Sean James/Celestine/Giovanni cosmetics; Makeup: Stephen Sollitto/Tomlinson Management Group

First Appeared on

Source link