Mankind Just Received a 10-Second Signal from 13 Billion Light-Years Across the Universe

A brief, high-energy signal recorded last year has become a focal point in astrophysics. The event, lasting ten seconds, came from a time when the universe was only a fraction of its current age. It has now been confirmed as the most distant supernova observed to date.

The signal’s exceptional distance, traced back more than 13 billion years, initially puzzled scientists. Its arrival set off a coordinated response from multiple ground and space-based observatories, culminating in a decisive confirmation months later.

Only after an intensive international follow-up campaign did the implications of this discovery become apparent. The event’s characteristics suggest star formation, death, and galaxy evolution may have progressed more quickly than previously understood during the universe’s formative stages.

A Signal from 13 Billion Years Ago

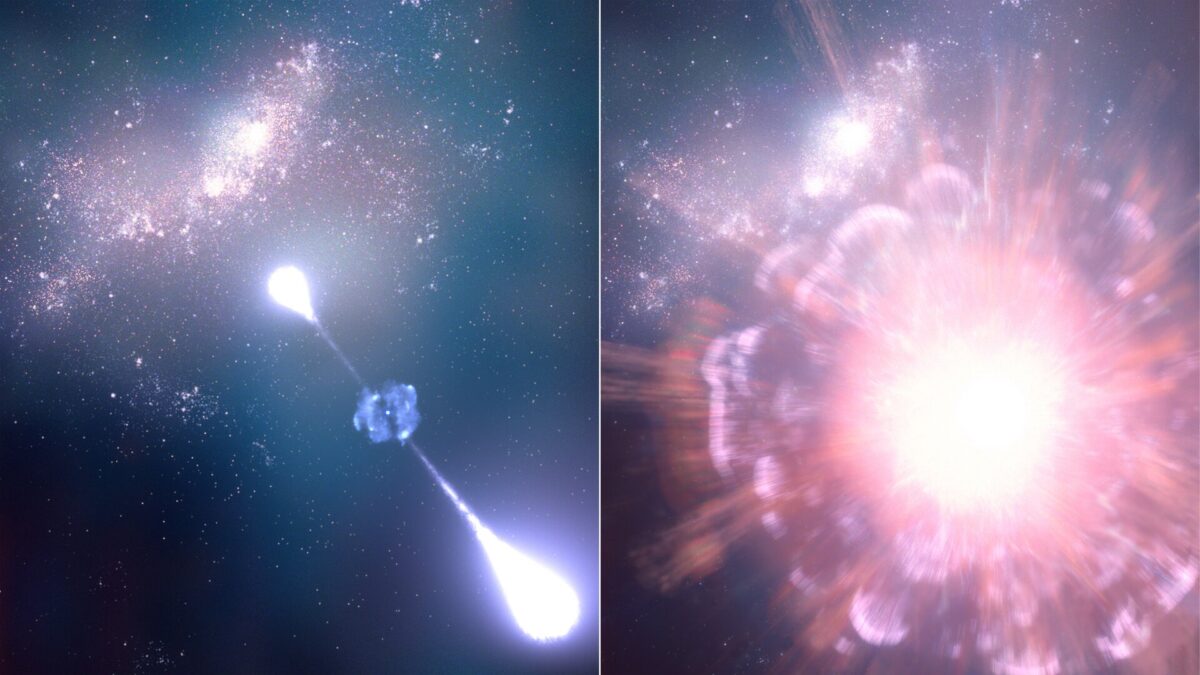

On 14 March 2025, the SVOM satellite, a joint mission between France and China, detected a long-duration gamma-ray burst, now designated GRB 250314A. These bursts are typically linked to the collapse of massive stars and emit focused jets of energy visible across cosmic distances.

Roughly 90 minutes later, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinpointed the burst’s location. Subsequent ground-based follow-up by the Nordic Optical Telescope and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) revealed an infrared afterglow. Spectroscopic analysis determined a redshift of z = 7.3, indicating that the light began its journey roughly 13.1 billion years ago during the Epoch of Reionization.

This measurement placed GRB 250314A as the most distant event of its type yet confirmed, exceeding the previous record held by a supernova detected at redshift 4.3.

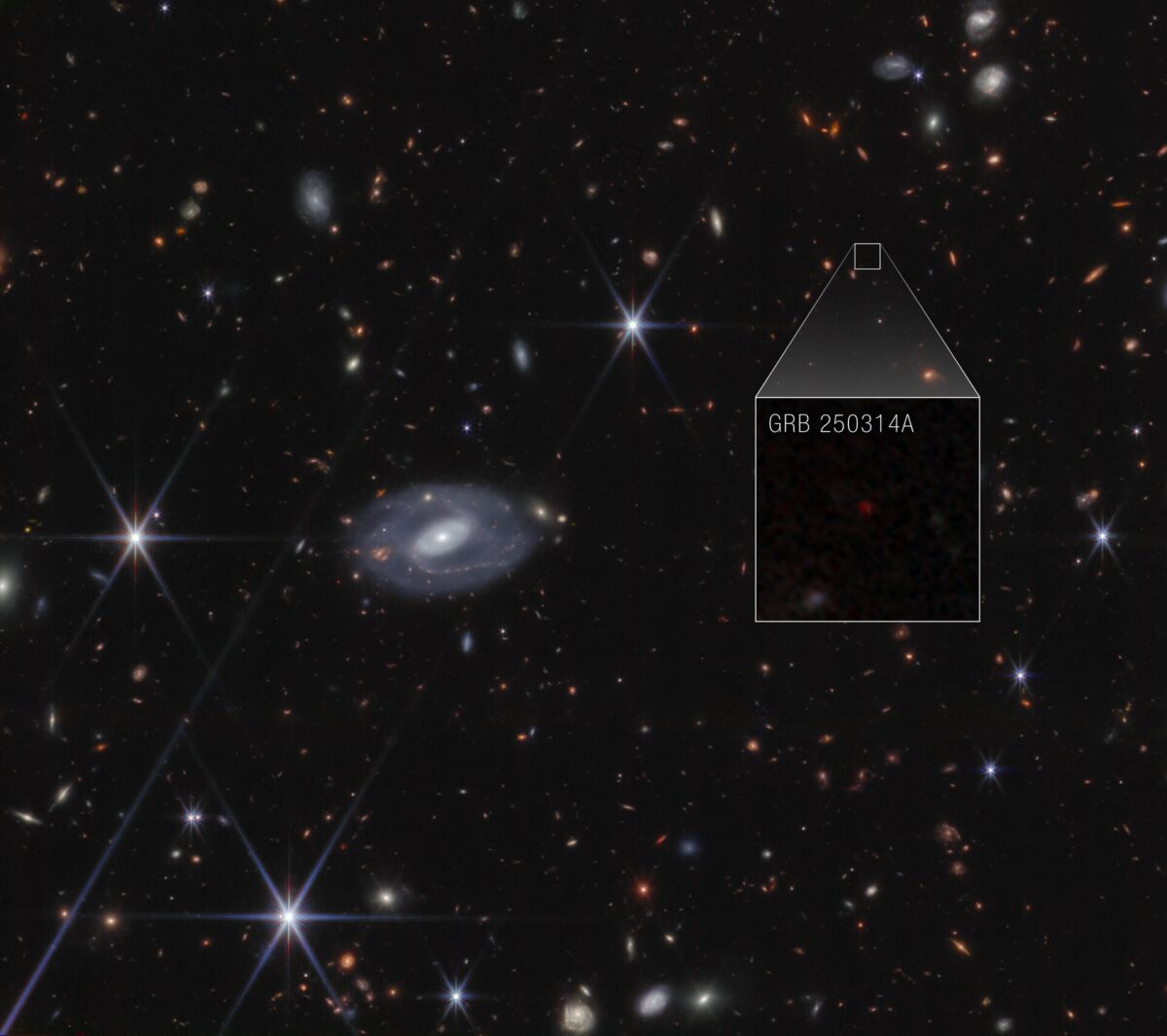

In response, the team activated a rapid-turnaround program using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Observations began in early July 2025, selected to coincide with the predicted peak luminosity of the supernova’s delayed light curve. Using its NIRCam and NIRSpec instruments, JWST successfully resolved the explosion and identified its faint host galaxy.

A Supernova That Defies Expectations

Data released jointly by NASA, ESA, and the Observatoire de Paris confirmed that the explosion was caused by the collapse of a massive star. Rather than showing the extreme asymmetry or elemental scarcity expected of so-called Population III stars, the supernova displayed characteristics consistent with modern Type II explosions.

This outcome has drawn attention to the possibility that stellar death mechanisms and chemical evolution were already established within a few hundred million years of the Big Bang. The photometric and spectroscopic profile of GRB 250314A closely resembles that of supernovae in the contemporary universe, suggesting a degree of evolutionary maturity in galaxies far earlier than theoretical models have typically assumed.

The host galaxy appeared compact and star-forming, broadly consistent with other high-redshift systems observed during the reionization period. However, due to the resolution limits of even JWST, detailed structural analysis remains beyond current capabilities.

New Clues About Early Cosmic Structure

The confirmed detection of a supernova at redshift 7.3 provides direct observational evidence that massive stars were collapsing and forming black holes well within the first billion years of cosmic history. GRB 250314A supports scenarios in which collapsars — rapidly rotating stars over 20 to 30 solar masses — seeded black holes and drove localized chemical enrichment processes much earlier than previously verified.

This finding challenges long-held predictions that the earliest stellar explosions would be uniquely energetic and chemically primitive. If GRB 250314A proves to be representative, models of Population III star deaths may require significant adjustment, particularly regarding their role in the formation of early galaxies.

Gamma-ray bursts from this era remain extremely rare in the observational record. Fewer than a dozen have been spectroscopically confirmed at redshifts above 6.0, and even fewer have provided the kind of afterglow and host-galaxy data that GRB 250314A yielded.

The event also marks the operational maturity of SVOM, which detected GRB 250314A just months after initiating full science operations. The satellite’s ability to trigger a global follow-up effort highlights the growing importance of space-based transient monitors in probing the early universe.

What Scientists Are Watching for Next

Multiple research teams involved in the current campaign have secured additional observation time on JWST to build a sample of similar high-redshift events. These efforts aim to test whether GRB 250314A is an outlier or part of a broader class of early-universe stellar explosions with unexpectedly modern characteristics.

The strategy relies on rapid-response coordination among satellites like SVOM, space telescopes like JWST, and major ground-based facilities capable of conducting infrared spectroscopy. Additional observations will focus on the light curves, afterglow profiles, and host galaxy properties of future high-redshift GRBs.

Unresolved questions remain about the prevalence of Population III stars, the rate of metal production in early galaxies, and the degree to which black hole formation influenced galactic structure within the universe’s first billion years. GRB 250314A introduces constraints that will need to be accounted for in updated cosmological simulations.

First Appeared on

Source link