Microplastics May Be Tied to Vascular Dementia Cases, Review Finds : ScienceAlert

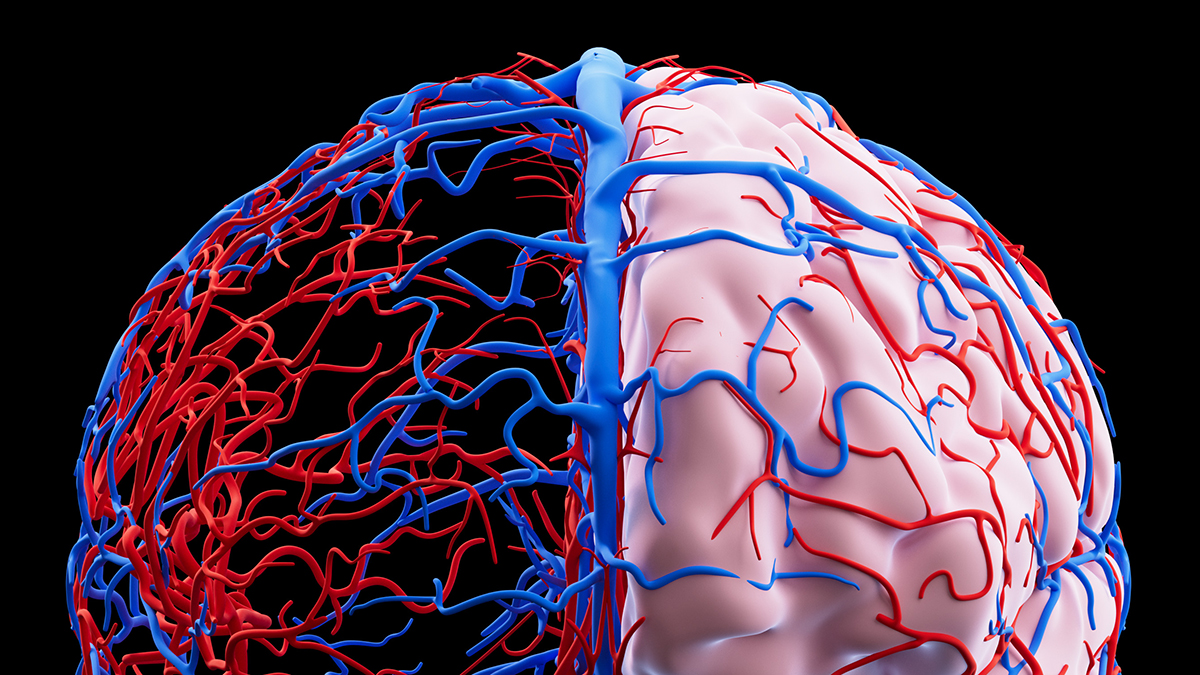

Vascular dementia is caused by blood flow issues in the brain: it’s one of the most common types of dementia, but not as well researched or understood as others.

Neuropathologist Elaine Bearer from the University of New Mexico is trying to change that.

In a recent review, she has suggested new categorizations for vascular dementia, each with unique pathologies – the actual biological changes in tissues and organs.

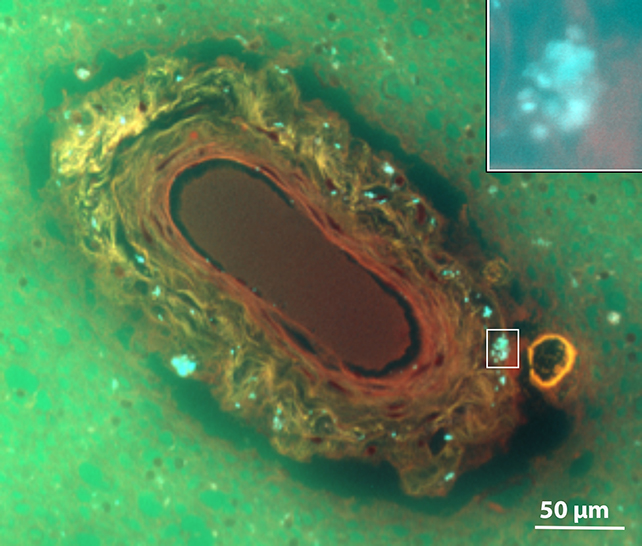

She highlights some significant overlap with Alzheimer’s disease, and she says her team’s novel microscopy method sheds light on how microplastics that have seeped into the body could be triggering or exacerbating cases of vascular dementia.

Related: Your Blood Type Affects Your Risk of an Early Stroke, Study Reveals

“We have been flying blind,” says Bearer. “The various vascular pathologies have not been comprehensively defined, so we haven’t known what we’re treating.”

“And we didn’t know that nano- and microplastics were in the picture, because we couldn’t see them.”

By analyzing both her own microscope work (which is published in a preprint) and studies by other researchers, Bearer has categorized the results of chemical staining on the cerebral blood vessels of people who died with dementia.

Through that analysis, several different disease processes were identified, all potentially contributing to vascular dementia. These included the thickening of arteries and small amounts of bleeding, as well as tiny strokes that can harm neurons.

The classifications are intended to be used in future studies of dementia, to explore how blood vessel damage may relate to disease. Every time we understand a condition more fully, that new knowledge can help in the development of treatments.

That extends to Alzheimer’s too, the study found. Some of the identified pathologies in vascular dementia overlap with Alzheimer’s, such as the presence of abnormal amyloid beta proteins. Further investigation into the relationship between both diseases could give insight into how different forms of dementia get started and progress.

Tiny plastic fragments, which are everywhere in the environment, also seem to be getting into the brain. While it’s not yet clear what the health impacts are, these pollutants could contribute to or be a product of damage or disease.

“Nanoplastics in the brain represent a new player on the field of brain pathology,” says Bearer. “All our current thinking about Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias needs to be revised in light of this discovery.”

“What I’m finding is that there’s a lot more plastics in [people with dementia] than in normal subjects. It seems to correlate with the degree and type of dementia.”

We’ve actually known about vascular dementia since the late 19th century, but as other forms of the condition have been easier to identify, diagnose, and track, a lot of research has been directed elsewhere.

Now there’s a new framework through which to approach different forms of dementia. Dementia cases all have their differences, and digging deeper into those variations could teach us more about what makes some people more vulnerable to brain disease than others – and what can be done in response.

“Describing the pathological changes in this comprehensive way is really new,” says Bearer.

The research has been published in the American Journal of Pathology.

First Appeared on

Source link