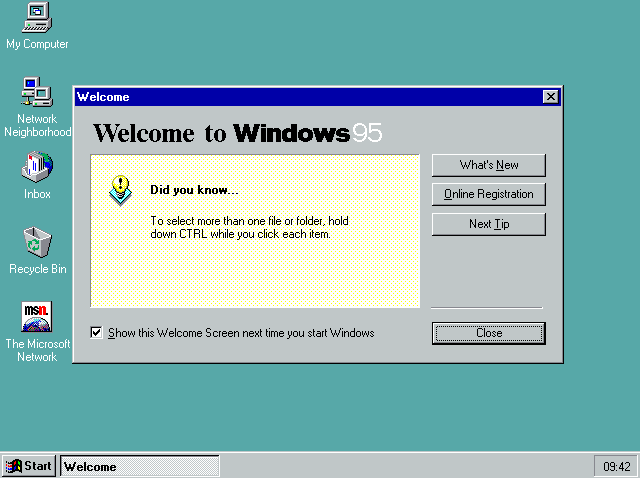

Microsoft veteran explains Shift restart Windows 95 trick • The Register

Microsoft’s Raymond Chen has explained why holding down Shift during a Windows 95 restart would get the system up and running again far faster than a full reboot.

Some old hands will nod sagely over the “Shift during Restart” trick, while others will wish they’d known about it three decades ago, given how often Windows 95 needed coaxing back to life.

Chen explained that the EW_RESTARTWINDOWS flag was passed to the old 16-bit ExitWindows function. The 16-bit Windows kernel shut down, then the 32-bit virtual memory manager shut down, before the CPU finally dropped back into real mode, and handed control to win.com.

For the uninitiated, real mode is how x86-compatible CPUs start – it’s a legacy mode with direct hardware access that’s now just a stepping stone to protected mode, which modern operating systems use. When win.com (running in real mode) received control, the CPU would signal it to start protected-mode Windows.

Chen noted that .com files are implicitly given all the remaining conventional memory upon launch. The memory can be released back to the system for other programs.

“In win.com‘s case,” said Chen, “it releases all the memory beyond its own image back to the system so that there is a single large contiguous block of memory for loading protected-mode Windows.

“If somebody had allocated memory in the space that win.com had given up for protected-mode Windows, then conventional memory will be fragmented, and the ‘try to get the system back into the same state that it was in back when win.com had been freshly launched’ is not successful because the expected memory layout was ‘one giant contiguous block of memory.’

“In that case, win.com says, ‘Sorry, I can’t do what you asked’ and falls back to a full reboot.”

Cue some thumb twiddling while the PC reboots.

Otherwise, win.com launched protected-mode Windows, and before long, the familiar user interface appeared on the user’s screen.

It’s a neat bit of engineering that enabled fast restarts, even if it could be undone by some naughty bit of code (say, from a device driver) grabbing that memory. And there was none of the “Hey, I’ve got an update that will probably break something” that bedevils modern Windows users. ®

First Appeared on

Source link