Scientists Stumble Upon Mysterious Tunnels in Desert Rocks

Buried in the limestone and marble of Namibia, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, scientists have found mysterious micro-tunnels, too small to see, too regular to ignore. These structures, invisible from the surface but perfectly aligned in the rock, appear to be the work of a microorganism unlike anything previously documented.

Geologists and microbiologists studying the formations believe these parallel, fossilized galleries may point to a long-extinct, rock-eating lifeform that once inhabited Earth’s deep mineral layers. Their findings, now published in Geomicrobiology Journal, raise new questions about how life can shape geology, and perhaps even the planet’s carbon cycle.

A Structure That Challenges Geology

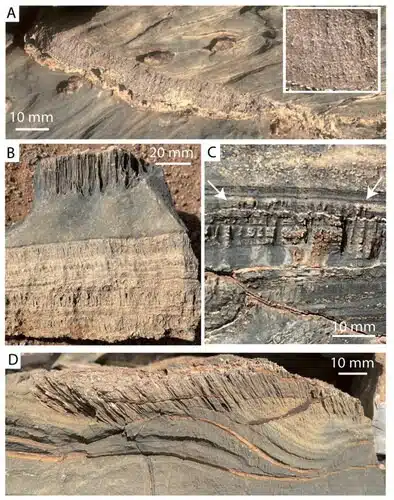

The first signs appeared over 15 years ago, when geologist Cees Passchier of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz discovered strange, vertical bands of tiny tubes drilled into desert marble. These micro-tunnels, about 0.5 mm wide and up to 3 cm deep, did not match any known geological pattern. Similar structures were later found in other arid regions, always with the same vertical orientation and spacing.

From the start, the tunnels puzzled researchers. They were found in Cretaceous limestone and ancient marble, always in regions exposed to intense desert conditions. What stood out was their regularity: each tunnel aligned vertically, spaced with precision, and limited in depth. They consistently emerged from natural fractures, as if something had taken advantage of weaknesses in the stone to begin its work.

A Mysterious Origin Points To Life Beneath The Surface

According to research, they systematically ruled out erosion, tectonic activity, and other non-biological (abiotic) processes after comparing multiple scenarios against the site’s observed features and context.

“What is so exciting about our discovery is that we do not know which endolithic microorganism this is,” explained Passchier, “Is it a known form of life or a completely unknown organism?”

That left only one possibility: a biological origin. The authors team began a systematic study of the chemical composition and isotopic signatures of the materials inside the tunnels. The findings pointed to something alive, something that once digested its way through solid rock.

Chemical Signatures of Ancient Activity

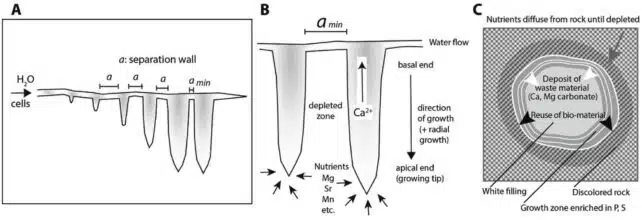

Inside each tunnel, scientists found a thin layer of calcium carbonate, chemically distinct from the surrounding stone. This layer was depleted in iron, manganese, and rare earth elements, suggesting that a selective process had occurred during its formation. According to their report in Geomicrobiology Journal, this was the first major clue that biology had played a role.

Further analysis showed carbon and oxygen isotope ratios inconsistent with natural limestone, a sign that organic matter had been broken down in the process. Using Raman spectroscopy, the researchers detected traces of fossilized organic carbon, likely from degraded microbial cells.

Another telling sign was the presence of phosphorus and sulfur along the inner tunnel walls, elements associated with membranes and proteins in living organisms. Yet, unlike known forms of microbial tunneling (such as by fungi or cyanobacteria), these structures showed no signs of branching or photosynthetic activity.

Patterns of Behavior Suggest a Collective Intelligence

Beyond chemistry, the geometry of the tunnels pointed to something even more unusual. The formations were not random or chaotic. As mentioned in the report, each tunnel appeared to avoid overlapping or crossing others, maintaining an organized, grid-like pattern.

This led researchers to suspect a form of chemical coordination, where cells responded to nutrient gradients or waste signals to avoid previously occupied areas. In modern terms, this resembles chemotaxis, a kind of chemical sensing found in some bacterial colonies.

It’s possible that these microbes dissolved rock using organic acids, then pushed the debris behind them as they advanced. In some tunnels, concentric layers of mineral waste were found, like growth rings, possibly reflecting seasonal changes in moisture or nutrient availability.

First Appeared on

Source link