What to know when your daughter has anorexia.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

I missed so many warning signs.

Sometimes my daughter (I’ll call her Olivia) wasn’t hungry. Fair enough—one less meal for me to cook or otherwise produce. (I hate producing meals.)

She wanted to make her own lunch for school instead of eating cafeteria food. Have at it. I noticed at some point that her special lunchtime breakfast burritos seemed to be getting smaller, but I didn’t think much about it.

She got more interested in cooking and baking in general, and would make food for her younger sister and me that she didn’t eat herself. I didn’t think much about that either. And since she liked cooking, I didn’t question why she was obsessed with food shows on TV.

She was also exercising a lot—Pilates, running. I think you can see where this is going. If I couldn’t, or didn’t, all I can say is that it’s hard to see warning signs if you aren’t looking for warning signs. At least it was for me. As glaringly obvious as they appear in hindsight.

Olivia seemed so perfect—smart, funny, kind, made straight A’s, had lots of friends, was on the cheer team and swim team. She was beautiful, tall and graceful with gorgeous wavy red hair and a gap-toothed smile. Her perfection was all the more amazing because of how improbable it was, given that our family was emerging from a major trauma: the death of Olivia’s father, my husband, from a particularly ugly form of brain cancer.

For a while after Bill died in the summer of 2022, I thought that Olivia and her sister might have dodged a bullet and somehow avoided being totally fucked up by what happened. They both seemed like they were doing pretty well. Olivia’s eating disorder was the first sign that this was very, very far from the case. My daughter has authorized me to tell her story. She has read and approved what I’ve written here.

Even with all those warning signs early on, it took our annual holiday visit to my in-laws’ ranch to make me see we had a problem. Olivia’s abstention from the orgy of festal dining was glaring. She wasn’t entirely not eating—that would come later—but she was eating very little. The event that sticks out most was when we went out to dinner at a pizza joint locally famed for circular french fries known as “spuds.” Olivia would not eat a single spud. She wouldn’t even taste one.

A day or two after we got back home to L.A., Olivia wanted to go running with me, and when she put on leggings and a tank top she looked skeletal. At my in-laws’ place, we’d all been in winter garb, and this was the first sight I was getting of her in tight-fitting clothes—or clothes that should have been tight-fitting—after what would turn out to have been very rapid weight loss. I can picture her in front of me, her legs so sticklike that her leggings flapped around them, her shoulder blades protruding like a baby bird’s wings, her painfully skinny arms jerking as she propelled herself slowly forward before sinking to the ground in exhaustion.

My feelings in that moment are painful to recall. I should have been focused on helping my daughter, but what I remember most is feeling ashamed to be seen with her. My beautiful baby had shrunk into a pale, wan creature hunched over at the side of the road, her condition so stark that everyone who saw us would judge me an unfit mother, or so I imagined. Someone might even report me to Child Protective Services. So in this moment of extreme distress for my child, I was thinking mostly about myself. I would suppress this memory if I could.

I took Olivia to see her pediatrician that afternoon. In an uncanny coincidence, it was Jan. 7, 2025, the day wildfires attacked Los Angeles. The inferno would ultimately spare our home, but there was no escaping the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty it produced, an eerie backdrop as we navigated an existential crisis of our own.

Olivia’s doctor took one look at her and instructed me to take her straight to the ER. She had gone from thin to dangerously underweight in a matter of weeks. I was stunned. I would have been even more stunned had I known that Olivia, who was then only 12 years old, would be away from home for the next nine months—save for a few days here and there when she would reappear, only to relapse and leave again. Yet, horrifying as that prospect would have seemed to me then, from my current vantage point I consider myself lucky. Because Olivia did come back home to stay, and some kids never do.

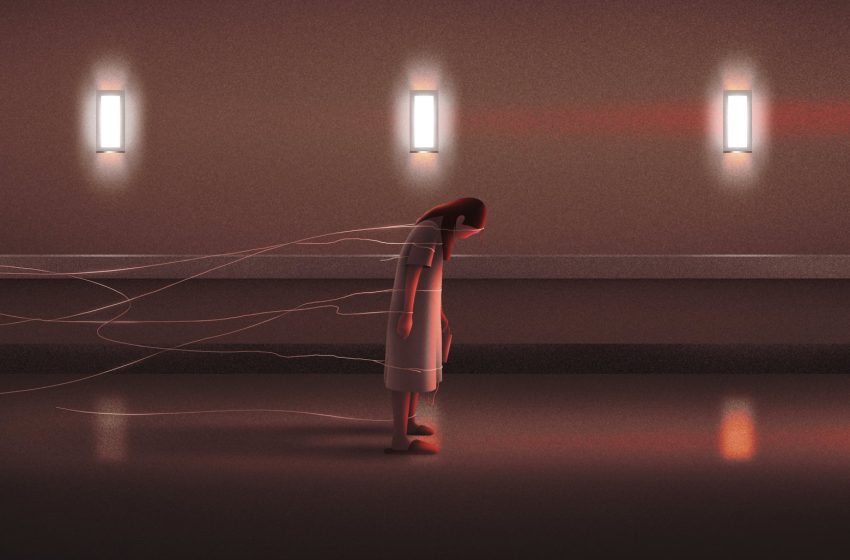

This is the story of an illness that took so much from my daughter and our family, and the hell she suffered to get her life back. Olivia is back at school now and firmly on the path of recovery, but I can still feel her eating disorder menacing, trying to regain a foothold and snatch Olivia away from us again. Every time she asks how many calories something has, or declines a bite of a dish that’s not part of her daily food plan, or asks where the scale is, or claims she looks fat—every time something like this happens, and it happens a lot, I sense her disease like an angry beast beating its wings close by, ready to pounce and carry her away.

Olivia spent the better part of a year in anorexia’s death grip, unable to see objective reality and determined to lose weight she didn’t even have. She bounced from one hospital and residential treatment program to another, before bottoming out in a hospital bed in Texas with a feeding tube down her nose. By the time she was finally willing and able to stand up to her disease, she had missed so many months of childhood, so much time with her sister and me, so many birthdays, school dances, mall hangouts, family movie nights, cheer team practices, swim meets, cousins’ weddings, trips to Tahoe, beach days, and on and on and on—everything that had constituted her life up until it was engulfed by the rigorous demands of her disease. In the process she had put my parenting skills to the test like never before—a test I’m still struggling to pass.

This is Olivia’s story, but it is not hers alone. Eating disorders are much more common—and more deadly—than I understood prior to Olivia’s diagnosis, and have become significantly more widespread in the wake of COVID-19. Reliable figures are hard to come by, as the federal government does not track eating disorder cases the way it does for many other diseases—an example of how eating disorders are not always taken seriously as the public health threat they are. However, a study commissioned by researchers at Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital just prior to the pandemic found that 9 percent of the population, or 30 million Americans, would experience an eating disorder in their lifetime, including 2 million kids and teens alive today who will experience an eating disorder before their 20th birthday.

The pandemic brought a perfect storm of risk factors, isolating kids and teens to consume endless social media while suffering relentless anxiety and stress. Children’s hospitals recorded a doubling of emergency room visits and admissions for eating disorders early on in the pandemic, according to a study published in the American Academy of Pediatrics. Those numbers never retreated to their pre-pandemic levels, other studies found, with the result that the eating disorder crisis mushroomed to threaten even more young lives.

Eating disorders have among the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, with some 5 percent of patients dying within the first four years of diagnosis, according to a 2021 study in World Psychiatry. Anorexia is particularly deadly, with patients at risk of organ failure and heart problems, as well as suicide.

Anyone can develop an eating disorder, and there is no single cause. Risk factors include family history and other mental health issues like trauma, anxiety, and depression, as well as social media, with its never-ending messages and images that tend to valorize being thin. Eating disorders can also give patients a seductive sense of control amid the chaos of external events (though succumbing to an eating disorder actually involves losing control, just as an addict is in the grip of their addiction). Olivia’s illness, as I came to understand, served as a powerful coping mechanism as she dealt with the fallout from her father’s death. It became an outlet for her distress that simultaneously promised to help her chase what she’d come to value most but couldn’t see she already had: a thin body.

After leaving the doctor’s office that Jan. 7 afternoon, Olivia and I spent anxious hours in the emergency room at UCLA hospital’s Santa Monica location, which has a program dedicated to acute eating disorder treatment. Olivia was admitted to the program late that night, and it didn’t take long for me to feel completely out of my depth as the doctors and nurses spouted jargon about “meal plans,” “refeeding,” “supplement,” and more, words that were meaningless to me at that time—a time of extreme naivete, as I look back on it now. My assumption then was that Olivia would get better at the hospital and soon come back home. It would take some time for me to understand that in fact we were at the very beginning of a perilous journey, one with no clear finale. The one thing that was clear was that Olivia would not be returning home anytime soon.

Our daily lives at the hospital revolved around Olivia’s meals. Her program practiced what was called “food as medicine,” and Olivia was expected to consume a very large quantity of food, something like 4,000 calories daily, divided among three meals and three snacks. This was her “meal plan.” When it was time to eat, they would bring in her tray, and she would have half an hour to finish her food. If she did not finish in the allotted time—and she almost never did—she was expected to “supplement” what she’d eaten with a protein drink making up the rest of the calories. When time was up on her meal, a nurse would walk in and look at her tray, and if there was any food left on it at all, even a tiny puddle of ketchup, the nurse would ask Olivia what flavor supplement she wanted. The nurses were trained not to make any comment on whether, how much, or what Olivia had eaten, or even betray the slightest reaction, and I was impressed at how consistent they all were about this. Even if she hadn’t taken a single bite, they would simply pick up her tray and ask her, in the most neutral tone, whether she wanted strawberry, chocolate, or vanilla. Olivia usually requested strawberry. She would then have 15 minutes to finish the supplement, with the threat that if she failed to do so they would immediately “tube” her, i.e., insert a feeding tube. They were so serious about this, and Olivia was so scared of getting tubed, that she always finished her supplement.

Olivia was weighed every morning at 6. They would have her go to the bathroom first and would weigh her in only her hospital gown. The numbers on the scale were shielded from her so she never knew how much she weighed. She also wasn’t supposed to see herself in the mirror, so the mirror in her bathroom was covered over with one of those paper mats or pads they have at hospitals, which kept coming untaped. Olivia wasn’t allowed into the bathroom anyway, except to shower; instead, she had to use a bedside commode, which would then be emptied into the toilet by a nurse or care partner, so that they could keep track of her output.

A few days into her stay, once she’d gotten strong enough, Olivia was permitted brief daily showers, and also short walks. Initially the walks were just around the unit, but eventually she was allowed to walk outside, in an exterior courtyard that had nice trees and grass, and a meditation area, and redbrick walkways, and rats. Olivia was attached to a heart rate monitor at all times, via a bunch of electrodes stuck around her chest, and she had to carry the monitor with her on her walks. It was the size of a small shoebox, with a handle on one end, and was fairly heavy. Olivia would carry it dangling from one hand, weighing her down enough to cause her to sway unevenly as she shuffled along in her oversized smiley-face slippers. I would try to carry it for her, but since it was attached to her by a cord that was only a few feet long, I would have to stay close by her and keep pace so it didn’t start to tug on her. Often she would grow irritated and grab the monitor back from me and carry it herself.

On these walks, Olivia almost never caught sight of another eating disorder patient. I would see them myself when I wasn’t with her, other upsettingly skinny girls in hospital gowns that hung on them like tents, but they didn’t see each other. People with eating disorders love to compare themselves to one other, and opportunities for this to happen appeared to be assiduously avoided.

Olivia’s constant companion at the hospital was a large device, at first glance a talking robot, that monitored her 24/7 to make sure she wasn’t hiding food or secretly exercising. This strange contraption was her “telesitter,” an unwieldy, missile-shaped creation set on wheels and equipped with two-way audio and 360-degree vision that allowed hospital staff to watch and listen to her at all times.

She part scrambled, part fell onto the floor, a pale figure with shiny red hair sobbing inside a flimsy hospital gown, connected by cords to a heart rate monitor, connected by an unbreakable bond to me.

“No exercising, please, Olivia!” the telesitter would squawk if she started moving her legs around too much. Olivia was not supposed to exercise apart from her walks, and the telesitter had a low bar for what constituted exercise. Sometimes I could tell that Olivia was trying to sneak in extra movement; other times I think she may just have been innocently moving her legs.

After several weeks of this, Olivia’s time at the hospital began drawing to a close, and her treatment team urged me to send her to a “residential,” i.e., a home where she would live with other teens with eating disorders and do group therapy and such. I was still holding out hope she might be able to come home, and I wanted to have a final discussion about it with the doctor in charge of her program. This doctor was a highly competent and intimidating person, much sought after by all the patients’ families because she was the only one who could definitively answer certain questions. Perhaps to prevent her from being mobbed when she did appear, her whereabouts seemed to be a closely guarded secret. She would simply show up at Olivia’s bedside with no warning, like Mary Poppins, and half the time I wouldn’t even be there. However, I tracked her down as I struggled to make a final decision about next steps, and asked her what would happen if Olivia didn’t go to residential. If she went home instead, what were the chances she’d end up back in the hospital?

“One hundred percent” was the unhesitating response.

That decided it, and I told Olivia she’d be going to residential directly from the hospital. She part scrambled, part fell onto the floor, a pale figure with shiny red hair sobbing inside a flimsy hospital gown, connected by cords to a heart rate monitor, connected by an unbreakable bond to me.

“Please, Mommy, don’t make me go, I don’t want to go!” I remember her wailing over and over, but I hardened my heart, and Olivia ordered me out of her room.

If there’s a villain in this story, it’s my insurer. I was disturbed to discover that our insurance company, arguably more than any other entity or person, was the arbiter of when Olivia’s hospital stay would come to an end, as it would stop paying once it was no longer medically indicated for her to be there. Doctors were the ones who were supposed to determine when something was medically indicated, of course, but they were under constant pressure from the insurance company, which was forever second-guessing their decisions. The more time Olivia spent in this world, the more I saw just how involved the insurer was every step of the way, and the more problematic this looked. Since decisions about time in treatment or moving from one treatment venue to another seemed highly subjective, I found it perturbing that insurance company officials who’d never even met Olivia were trying to call the shots. Most of the time I was satisfied with the ultimate outcome, but I came to understand that this was only because Olivia’s providers devoted untold hours to arguing with our insurer to justify a particular hospital stay or a transfer from one residential to another.

The reality, though, is that eating disorders are notoriously difficult to treat, for a variety of reasons. It is a mental illness that is all about the body, so treatment must address both body and mind, creating countless complexities. Patients may refuse to believe they need treatment, since eating disorder sufferers often are unable to recognize how severe their symptoms actually are. Olivia was constantly insisting that she was fine, that she was not sick enough to have a real eating disorder, that she was taking up a hospital bed that could be used by someone who was “really sick.” She was reluctant to part with her eating disorder, which for so long helped her cope in our arbitrary world. For months she was open about the fact that she didn’t want to recover, a process she equated to getting fat, and, as she told one therapist, she’d rather be dead than fat. There’s no single way to get patients to embrace recovery, though group, family, and individual therapy can help, as can education about nutrition and the medical implications of engaging in eating disorder behaviors. But for many patients it’s a simple matter of time, as they grind through months in treatment while their family and friends move forward out in the world. Gradually, they may question whether this is how they want to spend their whole life. This was how it happened for Olivia. At a certain point she was just over it, and didn’t want to see the inside of another hospital room or treatment center.

“It’s a really tough illness, and we just don’t have really good treatment,” said Melissa Freizinger, a psychologist at Harvard Medical School, speaking about anorexia in particular. “There’s so much about the illness I don’t understand, and I’ve been doing this for a really long time.”

Olivia and I were both full of nerves when the day came to leave the now-familiar environment of the hospital and go to the residential. Olivia had gained enough weight that she no longer looked sickly, though she was still 10 or 15 pounds shy of her “target weight” as established by the hospital based on her growth charts and other factors. (I actually was never very clear as to how this figure was arrived at, especially since it differed from one facility to another.) Her biggest anxiety about the residential was that she would be the “fattest one there.” She voiced this concern repeatedly, even after I tried to tell her how twisted it was.

We had little idea what to expect as we drove along crowded freeways from UCLA into the far reaches of the San Fernando Valley. What we found was a big, upscale house that from the outside registered as a single-family dwelling, albeit one with many cars outside. It had a large, sloping yard dotted with some lovely California oak trees, and the Kardashians were rumored to live nearby.

Inside were half a dozen other girls ranging in age from 12 to 17, all of them suffering from one eating disorder or another, most of them from similar racial and socioeconomic backgrounds (white, privileged). Not all teen treatment centers are single sex for girls, but many are, and this one was. I think the other clients were at the dining table when we arrived, and they offered Olivia a friendly greeting. Olivia would spend nearly four months at this facility, where she formed a couple of close friendships and found, I think, a sense of community, though I question how beneficial it really was. Most of the girls were older than Olivia, and she thought they were cool; I wondered whether that made having an eating disorder seem cool. They spent a lot of their time lying around in the “milieu,” as they called the common area (I found the word odd in this context but discovered that it is therapeutic jargon), listening to Gracie Abrams, and making friendship bracelets. I was perpetually called upon to provide more beads. It sometimes, or often, felt more like a summer camp than a treatment center. At one point Olivia told me she needed new underwear, since all the other girls had cute underwear, and this felt like some kind of a wake-up call. I ended up pulling Olivia out a week early. There was a confusing incident where she fell and hit her head, and though it sounded to me as if she might have had a concussion, no one seemed to be paying much attention. It turned out OK, but I was getting disillusioned with the whole thing. Plus, she had been there so long already, and I thought she was ready to come home.

Olivia relapsed so quickly it was head-spinning—she later told me she’d planned to relapse. The first day she was home she ate a little, and the next day she ate less, and the day after that she refused to eat anything at all or drink any water, and I had to take her to the ER. Also, I discovered she was secretly exercising at night. Her journal was open on the floor of her room, and I glanced at it without even intending to. “Exercises for getting skinny,” Olivia had written at the top of the page, followed by a list of ab stretches and the like. That was a low moment. I’d felt so hopeful about her homecoming, determined to keep her here even if it meant sacrificing all my time to cook her meals and watch her like a hawk as she ate them. I was still so naive. It wasn’t until we’d gone through this whole process two or three more times—hospitalization, residential, false-hope homecoming—that I completely despaired of my ability to keep Olivia safe and healthy at home. I wanted so badly for Olivia to be home with us, it was all I wanted, but it could never happen until she wanted to get better, and she still didn’t. I didn’t know when that would change. I didn’t know if that would change. It was getting harder and harder to believe that Olivia would ever get better.

Anorexia truly is like a drug addiction, except that skinniness is the drug. Left to her own devices, Olivia would attempt to starve herself by whatever means necessary, including lies and deceit. I believe she might have starved herself to death if it had been up to her—thank God it wasn’t (though once she turns 18 I guess it will be, which is a terrifying prospect). When she didn’t want to eat, there was virtually nothing I could do. She would just sit there with her lips firmly closed.

This was the case even if I’d gone so far as to prepare a somewhat advanced meal, a monumental effort for me. I was so excited when Olivia came home from that first residential that I made her a meal the facility recommended called a “harvest bowl,” requiring baked butternut squash, cut-up sausages, goat cheese, and a bunch of other ingredients. I actually had to get a friend who knows how to cook to help me execute this. Presented with the harvest bowl, Olivia just sat there with her mouth shut. I was crushed, but there was nothing I could do.

On one occasion I remember I threatened to throw Olivia’s iPad into the pool if she didn’t eat. Strangely, I can’t remember how that turned out, although I’m pretty sure I didn’t throw her iPad in the pool. I was successful only once in getting her to eat when she didn’t want to, and that was because she really wanted a haircut but I wouldn’t let her get one until she’d eaten a particular meal. So she ate that meal. I then tried to get her to eat another meal by telling her she could get her nails done, but it didn’t work. At another point I drew up a little contract for both of us to sign, in which she committed to trying her hardest to eat and I committed to trying to give up my own vice, nicotine pills. Regrettably, the contract was ignored, by both of us.

Around six months in, it had gotten so hard to hang on to hope that I found myself ordering others to hang on to hope. As long as they did so, I would have to too, was my confused logic. Then things got even worse.

The staff at whatever residential program Olivia then occupied contacted me to say she was not eating, and recommended transferring her to a residential facility that utilized feeding tubes (which that current program, along with many other residentials, did not). The alternative would have been sending her to the ER yet again. I can’t remember my exact thought process, but I guess it seemed as if I might as well try something different. The closest residential we could find with feeding tubes and an open bed was in Houston, and so we went there.

It was only May or June, but it was already so unbelievably hot and humid in Texas. We found ourselves wandering around an airport that seemed five times the size of LAX, and Olivia had no energy for airport wandering; I was worried she might pass out at any moment. I got her to the new residential. Like the others, it was at a spacious house in the suburbs, and everyone seemed nice. But the environment felt so alien to Olivia, who had never set foot in the South, and she was miserable. Nevertheless, I returned to L.A.

A day or two later, I got a phone call from someone at the Houston residential informing me that Olivia was on a “food strike,” and that they were going to give her a feeding tube. I authorized this. Then they called again, telling me that they’d tried giving her a feeding tube but that she’d refused to accept it.

I was speechless. It had not occurred to me that refusing to accept the feeding tube would be an option. If that were the case, why drag Olivia to Houston at all? But so it was, and I never understood whether the staff in L.A. who’d recommended that Olivia go to Houston to get a feeding tube knew that she wouldn’t actually have to get a feeding tube if she didn’t want one. An even bigger mystery was how Olivia herself knew that she could refuse the feeding tube, and even though we were now at mayday levels with her eating disorder, a little part of me felt proud of her balls. I’m pretty sure that I, at age 13, would not have been able to stand up to a bunch of grown-ups in that way, although maybe it was just her eating disorder taking charge.

I thought about when she was a happy little baby and an adorable toddler and a sweet little girl, and then I thought that she was still a sweet little girl, but now she was a sweet little girl who’d rather be dead than fat and had to be kept alive with a feeding tube in Houston.

I subsequently learned that many if not most residentials will not drop a feeding tube over a patient’s objections; they mostly leave that to hospitals. A hospital was now where Olivia would have to go, and after some incomprehensible dithering about which one it should be, the residential staff sent her on her way. Her conveyance was not an ambulance but a car driven by a young staffer who spent the hourlong ride gossiping with her boyfriend on speakerphone as Olivia desolately road shotgun. There were no other passengers.

I, meanwhile, made my way back to Houston, passing again through the biggest airport ever constructed into the worst heat and humidity that ever existed. By the time I made it to the hospital, Olivia was sinking. She had not had any food in two or three days, and she needed some nutrients right away. Since she’d been sent to the hospital for the express purpose of getting a feeding tube, my expectation was that she’d get a feeding tube pretty much immediately. I hadn’t reckoned with the confounding scenario of a hospital lacking expertise in eating disorder treatment, where the one doctor who understood the issue could be countermanded by an attending who wanted Olivia to try a few bites of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich first, to see if she might rediscover her love of eating. This patently absurd exercise was abandoned once the knowledgeable doctor got wind of it, but that took what felt like an eternity. I had not understood how good we had it at UCLA, where all the staff who deal with eating disorder patients are carefully trained on how to do that. I never saw or heard anyone at UCLA make a misstep such as talking about weight or size, or demonstrating a basic misunderstanding of how eating disorders work. All of that happened in Houston.

When the moment finally arrived for Olivia to get the feeding tube, she was ready for it. She had always feared feeding tubes, but by this point she seemed almost to want one—at least that was my impression. She was so clearly nearing a dangerous tipping point that perhaps she herself was frightened, and maybe it was a relief that the choice—eat or don’t eat—was being taken out of her hands. Certainly she didn’t fight it.

I cannot summon an image of the feeding tube being inserted. I’m not sure if that’s because I closed my eyes or turned my head to avoid seeing it happen, or if I’ve blocked out the memory. The image of her with the tube down her nose is indelible. It was a skinny yellow tube, placed at the outer edge of her right nostril, then looped over her ear and taped there to keep it in place. She sat up in that hospital bed so far from home, with that tube like a scar on her white skin, and I felt we had reached a new low, an extremity of pathos. I thought about when she was a happy little baby and an adorable toddler and a sweet little girl, and then I thought that she was still a sweet little girl, but now she was a sweet little girl who’d rather be dead than fat and had to be kept alive with a feeding tube in Houston. Maybe she never would get better at all. Maybe this would be Olivia’s whole life, going from one hospital bed and residential program to another, and never getting to lead a normal existence. I felt despair then, and I felt how helpless I was as her parent, no matter how much I loved her. Her eating disorder had gripped her so hard that nothing else mattered, and it might never let go.

Pretty much as soon as she got the feeding tube, Olivia wanted to start eating again, or at least drinking supplement, because she wanted that thing out. It was very uncomfortable. She kept thinking it was inserted wrong because of how painful it was at certain sites along her esophagus. Staffers were constantly wheeling in an X-ray machine to do chest X-rays to make sure there wasn’t something wrong. It always needed to be readjusted or retaped, and it hurt her nose. After a day or two of her drinking supplement, we started pushing to get the tube taken out, but that was a whole process. At a certain point I started threatening to pull it out myself because I was getting so frustrated. Olivia had also started running a low fever at night, although we weren’t sure why, and everything felt pretty hopeless. I focused on figuring out how to get her back to UCLA, and after a few more days we got the tube out and left with a good-riddance goodbye. We made it back to UCLA, and by this time that familiar unit felt like home.

Houston turned out to have been rock bottom. Olivia would still suffer one more relapse, and also it would turn out she had gotten COVID for the first time ever—hence the fever (thanks, Texas!)—but a few weeks later she started a different program at UCLA, a residential that was better than the other residentials, and somewhere in there something clicked. Her mindset made the all-important shift from wanting to be sick and viewing her eating disorder as an indispensable security blanket to wanting to get better and feeling eager to rejoin the world.

That doesn’t mean she’s all the way better or ever will be. She’s been home since early September, and she’s still hyperaware of how many calories she consumes. Our kitchen is festooned with nutritional-information handouts to make sure I produce balanced meals and snacks that contain the correct number of calories and not a calorie more. Going out to eat at a restaurant that doesn’t list calories on the menu is fraught, although it’s getting easier all the time. I drive to her middle school every day at noon so she can eat lunch with me in the car—otherwise, I will have no certainty that she’s eating enough. But still: She’s home, and she’s eating. She’s eating, and she’s home.

Nine months is a long time in the life of a kid, and Olivia changed while she was away. When I wasn’t looking, because I couldn’t, she became a teenager—and not just technically, though she did turn 13. The teenage Olivia wears a lot of makeup, swears like a sailor, and spends all her free time shrieking into the phone at her new best friend she met in residential. She’s always been tough, but she’s acquired a nonchalant swagger she didn’t have before, so that if you didn’t know, you might not be able to tell that she remains excruciatingly vulnerable and insecure, not to mention adorably sweet. Also acquired: a nose piercing (over my objections, though she denies this) and two life-size Justin Bieber cutouts, one of which is always on the verge of toppling over.

That teetering cardboard Bieber has become an unfortunate metaphor in my mind for Olivia’s hard-fought mental equilibrium. What worries me is that something could upset her balance and make her unhappy enough to slip into depression and reach for her eating disorder for comfort. I don’t think it will happen; I know that she’s strong, highly motivated, and equipped with a multitude of group-therapy-derived coping skills. But just as I hold my breath when tiptoeing around that unstable Bieber, I’m always holding my breath for Olivia, fearful of a fall that hopefully never will come.

Here are a few things I learned while living with my daughter’s anorexia: Don’t say anything about how she or anyone else looks. Don’t talk about food that’s good for you and food that’s not; food is food, we need it to live. Also, body dysmorphia is real, although it took me a while to grasp this. It’s just hard to understand, when your daughter is so thin she’s almost translucent, that she can see something so different when she looks in the mirror. But she does.

The hardest lessons to learn, but the most important ones, were about my job as a parent. I can—and must—support Olivia, encourage her, and most of all love her. I need to lead by example and establish positive meal routines for our family. But I can’t make Olivia do what I want her to do, make her “see reason,” make her get better or want to get better. It has to come from her. She just has to know that I’ll be there for her always. I hope she knows that. I think she does. Just in case, I’m going to go tell her again right now.

First Appeared on

Source link